When Giant Airplanes Ruled the Sky

The Great War triggered a trend toward big flying machines. Really big.

:focal(2175x1778:2176x1779)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/5f/b85f30b9-b130-4d97-99e9-e8f54cc627bd/02m_dj2020_nasm-1a37194_live.jpg)

I had been warned that there wasn’t much left of the airplane that designer Gianni Caproni had intended to be a transatlantic flying boat—the Noviplano—which had crashed and broken apart concluding its first and final flight, on March 4, 1921. There wasn’t. I’d trekked up into the Italian Alps to the Caproni museum in Trento only to learn that a small section of the hull and other pieces from the wreck of the Noviplano were in storage, awaiting conservation. Next I took the train to the Volandia Museum of Flight, just outside the perimeter fence of Milan’s Malpensa international airport. I was ushered inside to meet Gregory Alegi, a Yale-educated Italian journalist, defense analyst, and aviation historian. Alegi led me to the Noviplano relic display on the far side of the industrial campus of historic workshops and hangars that had grown up around Caproni’s original 1910 shack.

Now a museum park, Volandia still has the funeral chapel Caproni built during the Great War for unlucky student pilots. As billed, the Noviplano relics were sparse—a fuselage bracket here, a wing strut brace there. All had been fished from Lake Maggiore, sadly the only body of water the gigantic seaplane ever launched from or landed in—hard.

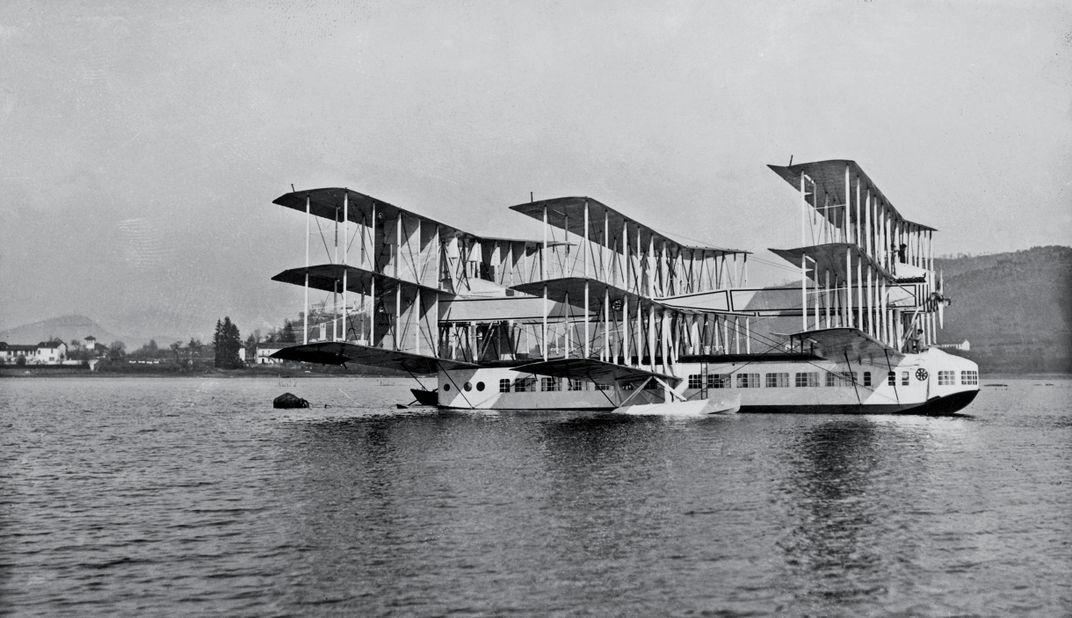

The Volandia fragments are displayed with blueprints, photos, and a large-scale model, allowing Alegi to illuminate the short career of the Noviplano, which he calls the Ca.60. (The “Ca” is pronounced “caw.”) The airplane was also known as the “Transaereo” for Caproni’s wildly ambitious mission: to carry 100 passengers in comfort and style across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Ca.60 had nine wings arranged in three sets of three. It had eight engines, all serviceable by mechanics in flight. Panoramic windows ran along both sides of the long cabin so that passengers, sitting in two wide rows, would have unrestricted views of the world below. Its rounded nose, integral flight deck, and streamlined seaplane hull made the Ca.60 fuselage look something like a modern wide-body jet. Add the three towers of linen wings, and it looked a lot more like a square-rigger under full sail.

Which led me to ask: Did this thing actually fly? Alegi clarified Caproni wasn’t at Lake Maggiore on the morning of March 4 but still in transit from the Malpensa factory. For nearly a month, pilot Federico Semprini had been conducting taxi tests on the lake to balance the hydroplane. It’s impossible to say what exactly caused Semprini to take off while his boss was still miles away. Did a lake boat suddenly swerve into the path of his taxi run? Did Semprini misjudge his speed? Or did Semprini just feel ready to fly?

“It certainly comes out of the water, but I think it was something like the flight of the Spruce Goose,” said Alegi, referencing Howard Hughes and the brief first-and-last flight, in 1947, of his giant seaplane, the H-4 Hercules.

The Spruce Goose landed safely. The Ca.60 broke up. By the time Gianni Caproni arrived at the lake, the pilot had been rescued, but attempts to pull the wreckage to shore worsened the damage. Caproni was, by all accounts, not a sentimental man, and by this point in his career, he was well acquainted with crashes. His journal recalls only that he took charge of the salvage operation upon his arrival.

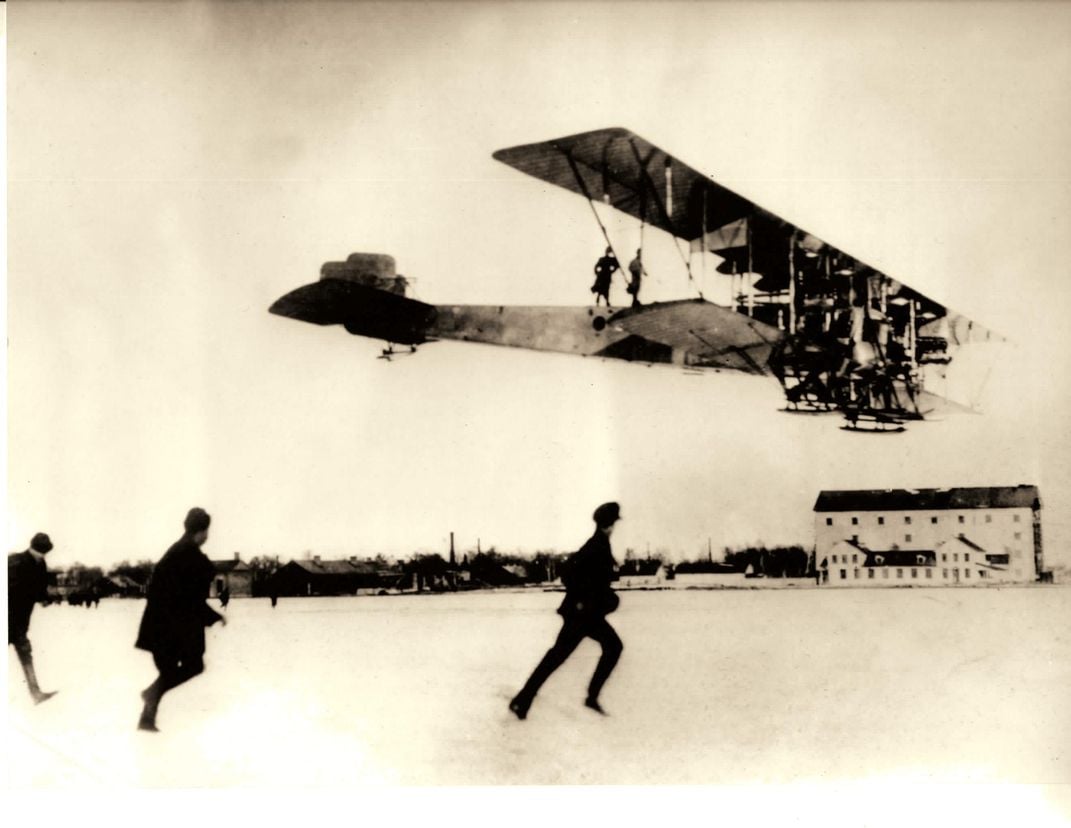

Caproni’s triple triplane was one of a startling and all but forgotten class of giant airplanes that arose in the technological hothouse of aircraft design in the years surrounding the First World War. The World War I giants came in all shapes but always in great size. The Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI German heavy bomber that terrorized London in 1918 had a wingspan of 138 feet, 34 feet longer than a 1942 Boeing B-17. Indeed, the R.VI was larger than any Luftwaffe aircraft used against Britain in the Second World War.

The giants had four or more engines and crews that included in-flight mechanics, radio operators, and defensive gunners. With the fighting stalemated in the trenches, all the great powers in aviation—Russia, Italy, Germany, Britain, and even, belatedly, the United States—bankrolled this frenetic arms race, commissioning design after design for exotic strategic bombers and long-range marine patrol craft. The modern memory of World War I aircraft is of rickety wood, wire, and canvas contraptions, but the giants, especially the German designs, employed the latest in alloys, monocoque stressed-skin construction, engine cooling, propeller shapes, reduction gearing, wind tunnel testing, and two-way radios.

If the giants are hard to see today, they are wonderful to imagine. To modern eyes, the heavy giants of a century ago look both futuristic and archaic—the aesthetic that science fiction fans refer to as “steampunk.”

As beautiful and strange as they look now, the giants were conceived as lethal weapons. There was nothing whimsical about the 21 dead and 32 injured in London by a Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI bombing raid on the night of February 16, 1918. The raids on London by German giants set off a patriotic howl for British revenge raids on Berlin. The British giant, the “Super Handley,” aka the Handley Page V/1500, was to be the instrument to deliver them.

All the Handley Page bombers were the result of the bluntest defense contract specification ever issued. There are two versions of the story, but both turn on the visit of Mr. Frederick Handley Page to Captain Murray E. Sueter, director of the Air Department at the British Admiralty in late 1914. Handley Page wanted clarification on the Admiralty’s request for a bomber with a 100-foot-plus wingspan and a 600-pound bomb capacity. Handley Page, who had been in the airplane business for all of four years at that point, was suggesting something a little more practical when Captain Sueter lost it. “Look, Mr. Handley Page, what I want is a bloody paralyzer, not a toy.” (In the other version, Captain Sueter merely relays a message to Handley Page from Commander Charles Samson who was in 1914 in headlong retreat across Belgium with what remained of the Royal Naval Air Squadron’s flying contingent. What was needed, Commander Samson supposedly said, was a “bloody paralyzer to stop the Hun.”) Whichever version one accepts, it should be noted that “bloody” is a very rude word in British English.

The first would-be paralyzers were the Handley Page O/100 and O/400 two-engine, medium bombers that became the British workhorses over the Western Front. Then, in the summer of 1917, the Germans renewed their air offensive against London by day with swarms of two-engine Gotha medium bombers. After suffering appalling losses, the Germans shifted the Gotha raids to night but added a small number of Zeppelin-Staaken R.VIs to the mix. The sheer size of the giants threw off British gunners (when visible, the giants appeared to be much closer in gun sights than they actually were) while the distinctive sound of the giants’ many engines droning overhead in the darkness unnerved Londoners.

Officially, the Super Handley was to be the core of the RAF’s new strategic Independent Force. Unofficially, it was bloody tit for tat. On November 11, 1918, three RAF Super Handleys were queued up in eastern England for a 450-mile raid across the North Sea to Berlin when the Armistice was declared.

The German response was the “Riesenflugzeug” (R-plane) development program. Berlin was suddenly willing to bankroll almost any contractor who had any idea for a very large airplane. In their authoritative history The German Giants, G.W. Haddow and Peter M. Grosz documented at least 37 giant R-plane (including pre-R-plane and R-seaplane) projects between 1915 and 1918. Of course, the German approach to profligate military spending came with stiff requirements for speed, altitude, bomb load, compact crew space, dual pilot controls, powerful self-starting engines that could be repaired in flight, defensive machine gun positions, and bomb bays or racks accessible to the crew. By 1917, R-plane specs included a wireless station and vibration-protected instrumentation.

Some German giants landed tail first with big skids on the prow to prevent nose-overs. Others landed on tricycle nose gear but with belt-and-suspenders tail skids. They landed on water on floats or as true hydroplanes with integral boat hulls. They were monoplanes, biplanes, triplanes, and sesquiplanes—a biplane wherein one wing has less than half the area of the other wing.

Late in the war, the Fokker company submitted a preliminary design for an all-metal monoplane with wing roots so thick that the mechanics reached the outboard engines from inside the fuselage.

The oddest R-plane was the Linke-Hofmann R.II. The builders took a proven single-engine biplane design and blew it up to three times original size. On the ground, the Linke-Hofmann appeared as an elaborate optical illusion. “It is quite impossible to grasp the immense size of the R.II just from photographs,” observed Haddow and Grosz. “The single air screw, the pilots’ cockpit, the gun mounts, and the conventional landing gear all trick the eye.” Only by mentally inserting a man alongside its five-foot-high wheels or its 23-foot-diameter propeller—“the largest single propeller ever built”—could you grasp the airplane’s mammoth scale, they said.

The Linke-Hofmann was 66 feet long and 23 feet high. Packed into its long nose were four Mercedes 250-horsepower engines coupled in pairs to a single propeller shaft. The gear tires were steel. It never flew in combat, but it apparently handled well in the air and on the ground. In a January 1919 post-Armistice test flight, a Linke-Hofmann ran off the end of the runway and plowed 79 feet through an ice-crusted snowfield without tipping over. The wheels left ruts 12 inches deep.

The most combat-effective R-plane was the Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI, which served on both the Eastern and Western fronts, including the raids on London. All the German giants were surprisingly tough. Of the 17 R-planes of all types lost in combat operations, only three were destroyed by enemy action, and only one was ever shot down by another aircraft. But giants on both sides of the conflict were vulnerable to bad weather, mechanical failure, and overwhelmed pilots.

In 1914, Zeppelin set up Dornier near the Zeppelin airship plant on Lake Constance in southern Germany. Dornier’s brief was to build the navy’s giant R-seaplanes completely in metal, using the many construction innovations developed for the Zeppelin airships, according to Jürgen Bleibler of the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen. For his seaplanes, Dornier drew on Zeppelin work with aluminum alloys, braces, and triangular girders to add strength and rigidity while holding down weight.

Still, the exotic materials of the time posed problems. Duralumin sheet metal had a tendency to exfoliate like the pages of a book or turn to white powder. “There were still hard technological problems with the new aluminum alloys,” Bleibler explains. “Therefore the Rs.I was a mixed steel-aluminum construction. Regardless of its failure, Rs.I structurally was years ahead of its time.” But other elements of the Rs.I—its engines, its propeller drive shafts, its instability on the water—were fully of its time. It never flew.

The Rs.II was technically a sesquiplane with a broad, wide top wing and a stubby half wing attached to the hull. Dornier always worked in close consultation with his engineers to refine or completely redesign as shortcomings emerged and the work progressed. The Rs.II’s rear fuselage began as a wire-braced box and then became a much simpler open tubular boom. The engines were moved from inside the hull to tractor-pusher pylons, which became a Dornier trademark.

For the Rs.III, Dornier shook up the components into a triple-decker sandwich—a monoplane wing and fuselage on top, engine pylons in the middle, and the cockpit in a wide hull on the bottom. It was a practical and durable aircraft. Dornier delivered an Rs.III to an Imperial Navy seaplane base on the North Sea in February 1918. It served for three years, continuing to clear naval minefields after the war’s end, before it was ordered destroyed by the Allied post-war disarmament commission.

The same commission also destroyed Dornier’s wartime masterpiece, the Rs.IV, an all-metal monoplane of true monocoque stressed-aluminum construction. The small lower “wing” on the hull had become a “sponson,” a stubby winglet projecting from the hull, which allowed Dornier to increase the seaplane’s stability in the water without widening it to grotesque proportions. This Dornier-patented feature gave the craft a quicker exit from the water at takeoff.

Here the history of the wartime R-planes supposedly ends. On the Allied side, cash-strapped governments cut the flood of airplane contracts to a trickle. Caproni and Handley Page tried to convert their giant bombers into civilian airliners with limited success. The Versailles Treaty banned Germany from manufacturing military aircraft for 15 years. But the treaty didn’t stop German engineers from designing aircraft to be manufactured abroad. Dornier launched an end run, moving some of his operations across Lake Constance to Switzerland.

In 1921, he struck a deal with Italian industrialists for a new seaplane factory near Pisa to manufacture the Dornier “Wal,” or Whale, a scaled-down (but still hefty) aluminum-skinned seaplane recognizably descended from Dornier’s Rs giants, according to Dornier expert Michiel van der Mey. “This was the realization of Claude Dornier’s dream of a giant passenger flying boat able to cover transoceanic routes,” he says. The Wal would go on to delight mail carriers, Arctic explorers, colonial administrators, and naval military aviators for decades. The Wal was the direct ancestor of Dornier’s spectacular 12-engine Do X super seaplane, van der Mey says, but the Do X was a commercial disaster.

It caused a sensation when it landed in New York harbor in August 1931, theoretically inaugurating transatlantic passenger service.

The actual trip, however, took 10 months because of breakdowns, accidents, and its roundabout route—Germany to the Netherlands to England to France to Spain to Portugal to West Africa to the Cape Verde Islands to Brazil to Puerto Rico to New York. In truth, the Do X was another Dornier aircraft ahead of its time: the largest direct descendant of the World War I giants—but also the last.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/fe/f8fe844d-6566-4d2a-b0bf-72be2e31f01c/02b_dj2020_b_si-91-17324_live.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/5f/b85f30b9-b130-4d97-99e9-e8f54cc627bd/02m_dj2020_nasm-1a37194_live.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/40/9740e235-e86c-4040-a110-b1efa2bd81df/02n_dj2020_dornier_nasm-1a36860_live.jpg)