When Slower Was Faster

The brains—and the physics—behind the 1955 Bendix win.

:focal(1250x2744:1251x2745)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/e1/13e143e8-e9d9-4eb4-a563-f1fca3133436/31g_jj14_f100aholloman_live.jpg)

By 1951, jets had replaced piston engines in the Bendix Trophy competition, the annual transcontinental air race known for the speed records set almost every year, beginning with Jimmy Doolittle in 1931. Bendix racers tried to outdo not only their fellow competitors but also the winners from previous years. The 1955 racers faced a high bar: In 1954, Air Force Captain Edward Kenny set a speed record with an average of 616.2 mph.

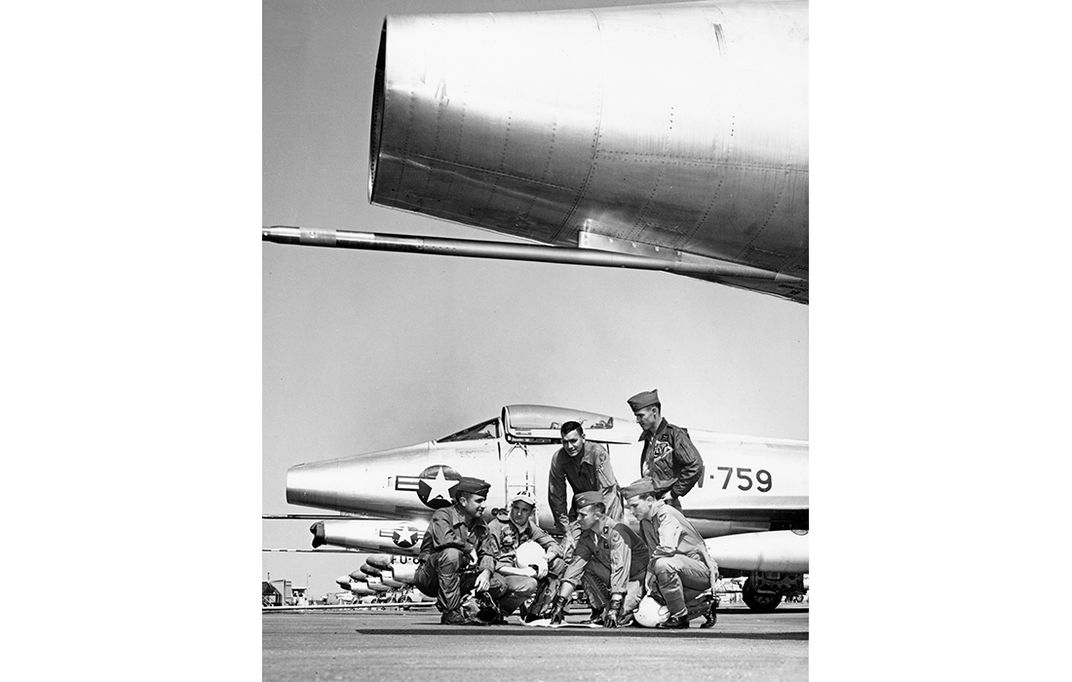

Entries for the 1955 race included the first fighter able to bust Mach 1 in level flight, five cocky pilots, a gutsy colonel, and my father, a bright second lieutenant with a bent for aerodynamics. That year, Carlos “Tote” Talbott was the group commander at Foster Air Force Base in Texas. Once the jets took over the Bendix race, the Air Force used the event as an opportunity to show off its frontline fighters; talking to a historian in 1985, Talbott recalled his orders in 1955: “I had the only F-100Cs in the Air Force. George [Air Force Base, near Victorville, California] had F-100As, which had considerably less internal fuel…. My group was selected, since I had the Cs to fly, but I was also directed to loan six airplanes to George so they could participate.” Each team had three pilots and one alternate, selected by the Foster and George wing commanders.

Talbott led the Foster team. At 35, the West Point graduate was already a colonel. He had flown 88 combat missions in a P-47 during World War II and had earned a Distinguished Service Cross. Squadron commander Major Charles Jones and Major Robert Meppen completed the team.

The race was scheduled for September 3, as the main event of the first day at the National Aircraft Show in Philadelphia. The Bendix Corporation created buzz in the weeks leading up to the race, using press releases to dribble competition details. One release described the role the Air Force weather service played in providing accurate race-day forecasts, especially of winds at the flight altitudes selected by each pilot. Late-summer winds at stratospheric altitudes were unpredictable: Tailwinds might push an aircraft to new records; headwinds could just as easily result in disappointing times.

The race, from the George base to Philadelphia, covered 2,325 miles. Planners soon realized it would have to be flown subsonically; supersonic flight required using the afterburner, which gulped fuel at an astronomical rate. Although the F-100 had inflight refueling capability, in 1955 the Air Force tanker fleet did not yet have the required probe-and-drogue equipment. Pilots had to plan for one refueling stop. To cross the finish line, a pilot had to pass a pylon situated next to the runway, then pitch up and return for a landing, after which he had to taxi under power until he turned off the runway. There would be no crafty planning on running out of fuel and gliding to a landing. Furthermore, to prevent last-minute shenanigans, a Tactical Air Command team inspected each aircraft to ensure it was properly configured and placed under guard.

Despite the strict rules, each pilot could develop his own strategy, including air and ground operations. The teams would fly the same type of aircraft, but many in the Air Force believed the George team would win because its maintenance crews had had much more practice with refueling and getting aircraft airborne quickly.

Bob Crim, a lieutenant at Foster in 1955, says, “There was no doubt in my mind that Talbott would win.” Another Foster lieutenant, Arnold Ebneter (my dad), developed a counterintuitive flight profile, based on North American Aviation performance data, that he believed gave Talbott and the Foster team the edge. According to Talbott, “Ebneter…had been an aeronautical engineer working for General Mills…. [H]e figured out my profile for me. He said, ‘You fly this.’ ”

F-100 pilots knew that as an aircraft approaches Mach 1, it rapidly produces more drag, and that at a lower altitude, an aircraft could fly faster before reaching Mach 1. Mach 1 near sea level is about 760 mph, but at 36,000 feet is only about 660 mph. The trade-off: At lower altitudes, much more fuel is consumed.

Dad created a graph of his calculations. He found that flying the F-100C in a “clean” configuration (no weapons or drop tanks) at military power (maximum power without the afterburner) produced Mach 0.935, or about 640 mph, at 28,000 feet (point A in chart below). However, at that power setting and altitude, the aircraft burned fuel too quickly, requiring a second stop if fuel reserves were to be maintained and tailwinds were light. Two solutions: fly at a higher altitude and slower speed to reduce fuel consumption (point C), or reduce speed at 28,000 feet (point D).

My father found another solution. If the Foster pilots used two drop tanks with 275 gallons of fuel each, additional drag slowed the airplane to Mach 0.925, but the extra range they would gain before refueling—necessitating only one five-minute refueling stop (point B)—enabled completion of the race with a slightly faster speed overall than the clean aircraft.

“Talbott flew several short practice races with my plan and realized that it would win,” Dad says, even though the advantage was less than three minutes. He suggested one Foster jet fly without the drop tanks. If there were strong tailwinds on race day, the clean aircraft would have the upper hand. However, eventually Talbott threw caution to the tailwind and decreed that all three Foster jets fly with drop tanks.

Talbott looked for other advantages. The F-100 used a drag chute to slow down when landing on short runways. Talbott decided not to use the drag chute at his refueling point, McConnell Air Force Base in Kansas, because it took his inexperienced crews too long to repack. He believed the McConnell runway was long enough to make the risk worthwhile. He also considered jettisoning the drop tanks once they ran dry. Crim remembers that after landing at Luke Air Force Base, “We drove to Flagstaff so he could sweet-talk a rancher into allowing [the Foster team] to deposit their empty tanks on his land.” It was all for naught: The Air Force nixed the idea.

While the Foster team polished their planning, the George pilots—Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Long and Captains Alvin Moorman and Wallace McCafferty—hatched schemes of their own. They also recognized the need for flying at lower altitudes and realized that a clean F-100, with only a single refueling stop, had marginal fuel reserves. However, despite reportedly flying up to 10 practice profiles, the George team apparently focused their overall strategy on achieving the shortest possible ground time. Moorman’s plan positioned refuelers so he could take off and head directly east without turning around, a tactic that could shave one minute off his time.

Arriving at George on August 30, the Foster team was pleased to find the George team aircraft bereft of drop tanks. However, the day before the race, drop tanks suddenly appeared on the George F-100s. Dad was sure Foster was doomed. But his hopes brightened that night during a conversation with Wallace McCafferty at the officers’ club bar. McCafferty mentioned that although he understood that different altitudes enabled different flying speeds, he wasn’t exactly sure what the trade-off was. He also worried about the drop tanks and mused that the George team didn’t understand why Foster was using them. Now, Dad says, he figured the George team hadn’t discovered the significance of the tanks, despite their presence on the George aircraft.

At dawn on race day, an offshore frontal system kept the ceilings over Philadelphia low. Newspapers ran stories about “hot-shot pilots cooling their heels” during the one-day delay. The next morning the weather was better, but the frontal system had produced headwinds out of the east. The racers knew there would be no records.

Because the winner would be the aircraft that achieved the fastest time en route, not the first to cross the finish line, race officials at George called counterparts in Philadelphia to relay start times as each pilot took off. Alvin Moorman took off first; his ground crew removed his drop tanks right before takeoff, causing Dad’s heart to leap. Talbott departed second, flying Lucky 777, serial number 53-1777.

As he saw the tanks removed from the remaining George aircraft, Dad’s hopes continued to soar. “I think they were just messing with us,” he says of the aircraft initially fitted with tanks.

The remaining four pilots were soon airborne, with First Lieutenant Herbert Ferlmann replacing Major Charles Jones, who dropped out after his afterburner failed to light on takeoff.

Dad was now confident that Foster would win, as long as the team didn’t do anything stupid en route. But at McConnell, things went awry. Talbott landed, refueled in five minutes, and got airborne again, but the other two Foster pilots blew tires and dropped from the race.

The unflappable Talbott pressed on. “I flew…whatever Mach I could get…at full military power, but if I found myself a little ahead on fuel, I would whack afterburner” to fly faster, he recalled. It worked.

Talbott had taken off second but he arrived first, roaring past the finish pylon at the obligatory 100 feet above the ground. His elapsed time: three hours, 48 minutes, and four seconds (average: 610.7 mph).

Despite the lackluster time, the Foster public affairs officer must have swooned when he saw the photograph of Talbott on the front page of the New York Times: canopy open, hair tousled by his helmet as he taxied to the ramp, beaming and waving to the crowd.

The George pilots had their own problems. Moorman’s refueling team was waiting in the wrong place and Maurice Long had a fuel-flow glitch. In an interview with Brigadier General Art Cornelius, Long recalled that, due to the fuel shortage, “I didn’t know what power settings to use, what altitude to go to, and after working on this thing for weeks and weeks and weeks, getting all these things right down to pounds and minutes…I spent the last half of it just sort of by guess.” He landed third, with 140 pounds of fuel—not even enough for a go-around.

Moorman fared somewhat better, but still slowed to conserve fuel. A reporter from the British magazine Flight wrote that Moorman “coasted in from Harrisburg, so dire was his fuel situation.” He finished second, in 3:50:04. McCafferty, knowing that a short maintenance delay had cost him the win, flew a conservative profile and finished fourth.

Talbott told Dad to take an overnight flight from Los Angeles to Philadelphia to participate in the Monday celebration. The next day, Dad also had the privilege of flying Lucky 777 back to Foster. The plan was for the four race-finishing F-100s to depart together, and as the pilots waited for the ground crews to ready their airplanes, the rivalry rose again.

Dad remembers, “Moorman was still stewing over losing the race. He complained that it was a fluke that Foster won, and he kept arguing about what he could-a, or should-a, or would-a done to win the race. I finally got tired of hearing it and told him the only way he would have won was to use the drop tanks.” As the red-faced Moorman stomped off, McCafferty grinned and asked if Dad would let him in on the secret, now that the race was over. This time, he obliged.

Talbott retired as a three-star general, McCafferty was elected to the Delaware Aviation Hall of Fame, and, 55 years later, Dad used his engineering and piloting skills to set a world distance record in an airplane of his own design, flying non-stop from Everett, Washington, to Fredricksburg, Virginia, nearly the same distance as the 1955 race. Lucky 777 was damaged in an accident a few weeks after the race. It was repaired, then, while assigned to the Colorado Air National Guard, destroyed in another accident in 1961.