Wanted: One Ercoupe, Lightly Used

Learning to fly was the easy part. Try buying an airplane.

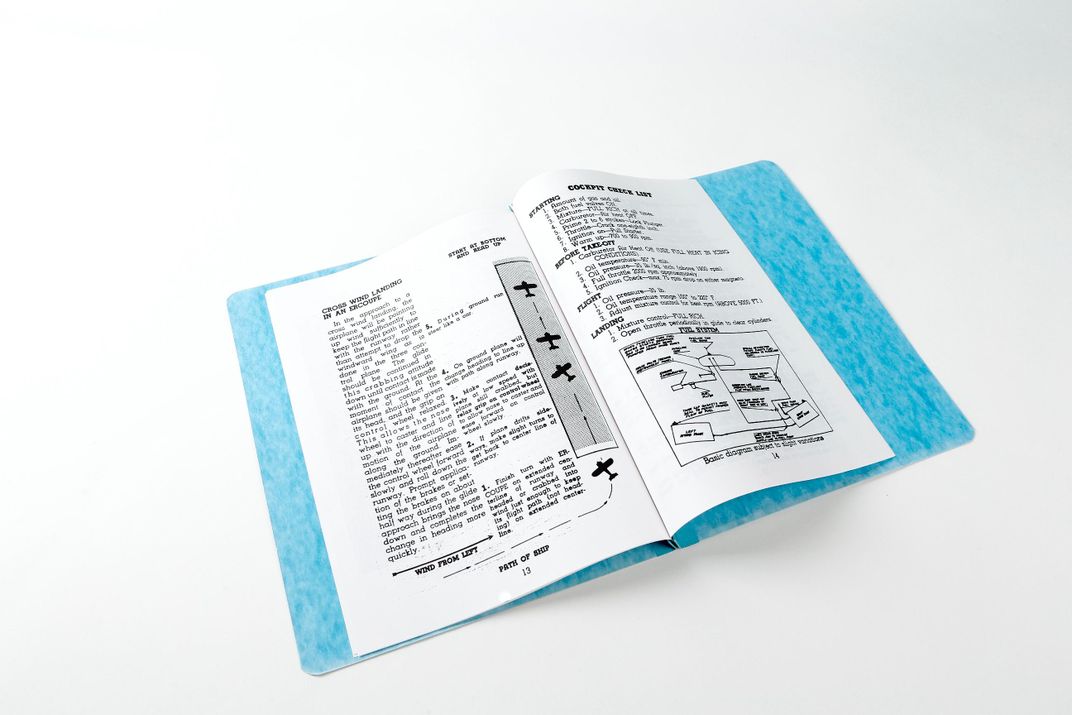

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/95/8a9542b9-4f35-4833-89e0-fe9918aaf507/17c_jj2017_williamduboisdsc_4662_live.jpg)

If you’ve never heard of the ERCO Ercoupe, I forgive you. There was a time I’d never heard of it either. Now I’m spending all my free time online, hunting for one to buy. There are plenty for sale, but I’m encountering some problems.

Some of the airplanes are too heavy.

Some are overpriced.

Some have already sold by the time I call.

One is missing its engine.

One guy refuses to sell his Ercoupe to me when I say I intend to use it for flight training. “My plane is much too pretty to be abused in that way,” he says, and hangs up the phone.

Another guy wants cash and only cash. I don’t think I’ve used cash in a decade. Not even for a hamburger. I can’t imagine traveling cross-country carrying $30,000 in hundred-dollar bills. Only criminals do that, right?

I would much rather buy a new airplane than a used airplane, especially since the used airplane is older than I am. Ercoupes haven’t been mass-produced in more than 40 years. But a brand-spanking-new light sport costs $130,000 or more. A “legacy” airplane runs a fraction of that, with most selling between $20,000 and $30,000.

I could’ve shopped for an Aeronca, an Interstate, a Luscombe, a Piper Cub, a Porterfield, or a Taylorcraft. Those are the other “legacy” light sport airplanes: Near-antiques that, due to their weight, power, simplicity, and two-seat design have been grandfathered into the Federal Aviation Administration’s Light Sport Rule establishing a simpler set of requirements for new pilots, and a less-stringent medical requirement for already-certified pilots like me.

But the Ercoupe was the only light sport that had the right combination of power and weight to operate safely out of my high-altitude home base. I need at least an 85-horse engine. Many of the legacy Light Sports are powered by 65-horsepower engines, and pilots based at my field tell me that in the summer I won’t even be able to get up to the pattern altitude with 65 horses. And I need a useful load of at least 450 pounds for two souls on board with enough fuel to fly for two hours, plus legal reserve. So the Ercoupe was the logical choice.

But it was also was the choice that fed my soul.

It’s a cool-looking airplane. Why own a boring-looking one? The rest of the pack are high-wing, tail wheel, tube-and-fabric affairs. The Ercoupe is low-wing, tricycle gear, and all metal, with twin rudders and a fighter-like canopy.

I knew buying an airplane wouldn’t be simple. I did my homework. I read what the experts said. I talked to other pilots who’d bought aircraft. I understood the purchase process: Title search, deposit, pre-buy inspection, test flight, escrow, title transfer, and state and federal registration. It’s more like buying a house than a car. But I never thought for one second that finding an airplane to buy would be a problem.

After months of frustrating web searches, I found one that fit the bill. The price was right. The hours were right. The weight was right. It had a warbird paint job, olive green with white Normandy-invasion stripes on the wings and empennage. After some trepidation, I decided I could live with the look. The cockpit was in horrible condition, with a scratched-up panel filled with faded and cracked instruments. But no problem, I thought: My family and I can handle a cosmetic overhaul of the interior.

I talked to the owner at length and we struck a deal. Now all I needed was to get a qualified mechanic to give the plane a pre-buy inspection. I got a list of Ercoupe mechanics from the Ercoupe Owner’s Club, and made a couple of calls to North Carolina, where the airplane was. I took its location as a good omen, North Carolina being the birthplace of powered flight and all.

The owner agreed to ferry the Ercoupe over to the mechanic I chose, and I started planning the cross-country trip to bring the little “Army” plane home with me to Las Vegas. Any flight between two airports 50 nautical miles apart is technically considered a cross-country, but this would be an epic cross-country: 1,411 nautical miles traversing a full two-thirds of the continent.

A week later I got a call from the mechanic. There were issues. The fuel tanks leaked, the Ercoupe weighed 300 pounds more than the owner thought it did, and the engine was nearly shot.

Crap.

To his credit, the owner returned my deposit, which he wasn’t legally obligated to do, and I was only out the $545.33 inspection fee—a good investment compared to owning an airplane you can’t use.

Back to shopping I went.

Next, I found a lovely red and white ’coupe with the look of a classic car from the drive-in era. Communication with both the elderly, nearly deaf owner and his more email-savvy nephew was a challenge, to say the least. The owner seemed a bit paranoid, with a long list of tales about people who tried to cheat him; his paranoia had the effect of making me paranoid. The negotiations dragged out over weeks. Eventually we struck a deal despite a number of occasions on which I felt the impulse to run away, like when he flip-flopped over using an escrow company. But after spending hours staring at pictures of it online, I was hell-bent on buying that airplane. I had fallen in love. Which meant I was thinking with my heart, not my head.

The owner agreed to the pre-buy inspection. He agreed to ferry the airplane to the mechanic. But he refused to leave the airplane with the mechanic for more than two hours, saying that in the past when he’d let it out of his sight it had been damaged. The mechanic said that wasn’t enough time. The old man wouldn’t budge. The deal fell though, and I lost my $500 deposit. Which, added to the $545 inspection fee for the first Ercoupe I tried to buy, meant I was now down more than $1,000.

I was learning that you can spend a lot of money buying an airplane and still not have one.

Sick of looking for an airplane, I placed a “wanted” ad. The next day the phone rang. The seller was reasonable and easygoing, and his airplane fit the bill perfectly. Every element of the sale went smoothly. After months of trouble trying to find an airplane to buy, the final chapter was so simple it was anticlimactic.

Except for the fact that the tale didn’t end there.

I never thought for one second that finding a hangar for my new airplane would be a problem….