Robots to the Rescue

Your next 911 call may fetch a drone.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/dc/63dc0c8b-af12-4eec-a051-e04f8ce2e8b9/04f_jj2017_kmaxyumaarizona1.jpg)

The roaring fire rose out of a grassy field in upstate New York last November 8, Election Day. Thick black smoke billowed skyward—but not for long. Minutes after a five-pound quadcopter Indago drone used an infrared camera to locate the flames, a gray twin-rotor Kaman K-MAX helicopter swooped in, filled its enormous Bambi bucket from a nearby pond, and dumped 3,000 gallons to extinguish the fire. But the day’s danger wasn’t over: Another drone—this one a small, hand-launched Desert Hawk—located a lost camper who had been trapped behind the fire and helped lead in a Sikorsky S-76 helicopter, which identified a suitable nearby landing zone and settled onto it to provide the camper the means to escape.

On the surface, the whole scenario appeared ordinary—precisely what unfolds on a regular basis during America’s increasingly long and costly annual wildland fire season. Yet every aircraft involved was a drone, and the carefully coordinated ballet by the four of them happened with only a little help from humans (mostly to transmit or confirm coordinates).

The demonstration, by Lockheed Martin and its subsidiary, Sikorsky, had been choreographed to show how four of its expanding family of uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) could work together in the field to fight fires and conduct search-and-rescue operations. The crowd of observers gathered at the old Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, New York, included officials from the federal and state government who hope that, sooner than later, these technologies will be brought to bear on seasonal wildfires out west.

Just a week before that firefighting demo, Urban Aeronautics’ Cormorant—a one-ton cargo-hauling UAV that looks something like a flying Toyota Prius—wobbled into the air over an Israeli field and completed a fully autonomous flight pattern—the onboard computers decided where and how to fly without any human intervention whatsoever—before settling back onto a roadway. The Cormorant, formerly known as the Air Mule, relies on rear-mounted fans and internal ducted rotors, which give it a vertical-takeoff-and-landing (VTOL) capability. While delivery drones and the 300 quadcopters that joined Lady Gaga’s Super Bowl halftime show may be the UAVs that capture the public imagination, the drones that will have a real impact on American life will likely look a lot more like the ones in the firefighting demo and the Cormorant. Indeed, both Lockheed Martin and Israel’s Urban Aeronautics say they see the greatest near-term potential for non-combat drones simply to automate what they refer to as the “dirty, dull, and dangerous.”

**********

Domestic drones so far seem to have more promise than actual achievements. The Federal Aviation Administration had been moving cautiously to open up drone use: As late as 2014, it had approved only two waivers to operate UAVs for commercial purposes, both for very limited use in the Arctic. But in mid-2016, it released a set of regulations for the routine commercial use of drones under 55 pounds, requiring the pilots to pass a written test and establishing certain limitations, like keeping the drone within line-of-sight and under an altitude of 400 feet. In 2016 the agency said it expected some 600,000 commercial drones to flood the nation’s skies within a year.

Farmers are turning to small drones for crop monitoring and field mapping, generating data to maximize crop yields. Filmmakers and television producers use drones for aerial photography, and drones are now being driven by wedding photographers and real estate agents. Lockheed has sold roughly 1,000 Indago UAVs; while its largest customer for them is the Pentagon, they’re increasingly being adapted for civilian use too. Companies like Trumbull Unmanned and Canadian UAVs, both of which do oil and gas industry work, use them for rig and pipeline inspections. The Heliwest Group was contracted in 2015 by the government of Western Australia to chart progress against a brushfire, which helped save an estimated 100 homes and $50 million in property. Another Indago, contracted by the government of tiny Pacific island Vanuatu, helped map more than 2,500 acres of the island after a typhoon, surveying roughly one square mile in each 45-minute flight, the limit of a single battery charge.

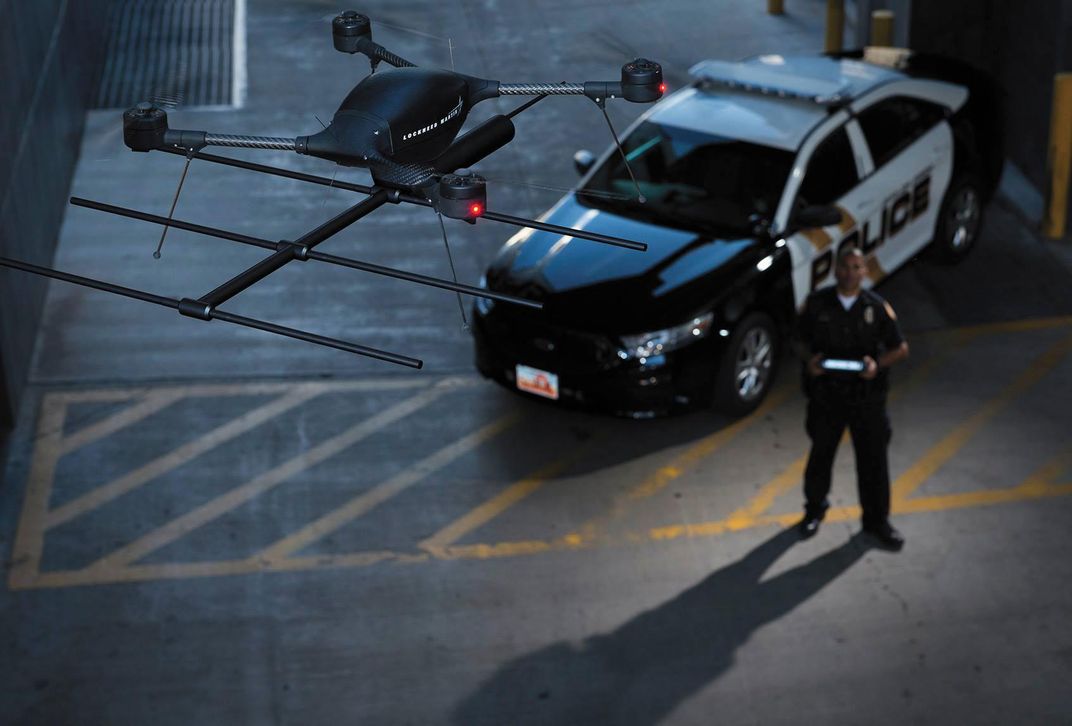

In the United States, regional law enforcement agencies are also beginning to rely on Indago UAVs for search-and-rescue and accident scene reconstruction. Lockheed has worked closely in recent years with Project Lifesaver, a nonprofit that helps people with conditions that might make them likely to wander away from home. Clients have tracking bracelets or anklets, and Lockheed offers an Indago model with a Project Lifesaver antenna to help quickly locate missing persons. (In May 2013, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police became the first agency to save a life with a drone, when a Draganflyer X4-ES used infrared sensors to locate a car accident victim in Saskatchewan.)

Following smaller drones into commercial careers, larger UAVs have a longer development period. Rafi Yoeli, the founder of Urban Aero, says none of these UAVs can do much beyond imaging. When disaster occurs or a large construction project looms, drones are still limited in their ability to help. “All you can do is send a high-quality drone with a high-quality camera to get very good pictures of it,” Yoeli says. “You can’t actually do anything about it.” Projects like his Cormorant, Lockheed’s uncrewed K-MAX and Sikorsky’s uncrewed S-76, called SARA, seem set to be the first to shift UAVs from observers to participants.

**********

Israel has long been a leader in UAV development. The first use of a UAV in wartime occurred in 1982, during the Israel-Lebanon War, when Israel used drones for video surveillance, and it’s a legacy that has helped shape Urban Aero: Four of the company’s staff, including its chairman, worked on that original UAV.

Yoeli spent most of his career working on aviation projects—including previous UAVs—and first explored internal rotors as part of an attempt to make kit helicopters for hobbyists. At that time, the technology of ducted rotors had lain dormant for almost four decades, ever since 1963, when development of the Piasecki Airgeep—a vertical-takeoff machine meant as a smaller, easier-to-use complement to conventional helicopters—was halted at the prototype stage. “The technology of the 1950s was not sufficient to overcome the inefficiencies of internal rotors,” Yoeli says. “You just lost too much thrust. I thought we could clean off the dust of this old Airgeep.”

Because of its protected rotors, the Cormorant can take off and land in roughly one-fifth the footprint of a Bell 206 helicopter, making it ideal for emergency medical services, which routinely require helicopters to land in populated areas not suited for them. “Emergencies don’t just happen in open and flat terrain,” Yoeli says.

That unique design helps the Cormorant carry a payload of around 1,000 pounds and yet also fly carefully through crowded urban landscapes. Yoeli says he foresees a day when urban fire departments can send a Cormorant to hover outside high-rise buildings and spray retardant or foam to quell fires within. “It takes about a minute for a fully loaded firefighter to climb a floor, so when there’s a fire on the 40th floor, you have 40 minutes to get up there,” he says. “We can actually butt against a building and dump into a floor a thousand pounds of fire retardant. You can do it within 10 to 20 minutes.”

Or the Cormorant could be used to replace crewed helicopters for powerline inspections, and even repair bridges or dams, using robotic arms operated by a pilot on the ground.

Meanwhile, Kaman’s K-MAX—a rugged synchropter whose angled interlocking rotors eliminate the need for a tail rotor and help keep the helicopter’s center of balance directly over its cargo hook—has become a workhorse for the timber industry because of its lift capacity and stability in a hover. Only 38 K-MAX helicopters were built originally—the production line was shut down in the early 2000s—but early this year, Kaman announced it would reopen production because of fresh demand. Once Kaman builds the helicopter, Lockheed buys them and turns them into drones.

To comply with FAA restrictions while moving between locations, the K-MAX can be flown by a human pilot in the cockpit, yet a single flick of a cockpit switch turns the helicopter into a UAV. That ability to blend the crewed and the uncrewed has made it much easier for Lockheed to make government officials comfortable with its experiments.

Urban Aero’s Cormorant will retail for $2 to $3 million, says Yoeli, similar to the cost of a Bell 206; Lockheed estimates that its larger, longer-range, heavier-lifting K-MAX will cost around $10 to $12 million.

Yoeli says that while he imagines the military and urban governments might purchase their own large-scale UAVs, he expects most to be rented to customers like energy companies and construction firms. “For civilian uses, you’d probably establish this as a service,” Yoeli says. “The business model side of this is non-trivial.” In other words, only the largest companies will probably need a Cormorant often enough to justify buying one, but buyers could make a living renting them out in much the same way charter aviation firms do.

Cargo-hauling will certainly be key, helping to replace drivers in treacherous conditions and terrain, like the “Ice Road Truckers” who deliver supplies across the Arctic. Delivery of medical supplies to remote regions will also be a crucial service undertaken by drones: In Rwanda, Zipline is already using a fleet of small drones to deliver blood supplies.

**********

The future of large, cargo-carrying UAVs might be closer than it appears. The K-MAX has already proven itself in tough conditions: During surge operations in Afghanistan, the U.S. Marine Corps turned to K-MAX as part of a massive effort to shift cargo away from attack-prone ground resupply convoys. Lockheed won what ultimately became a $45 million contract to use K-MAX for cargo hauling, but when it deployed to the field it was a decidedly unproven technology; Lockheed had flown K-MAX just 13 hours in fully uncrewed mode. But it worked: On December 17, 2011, the Marines’ Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Squadron 1 used an uncrewed K-MAX to deliver 3,500 pounds of food and water to the remote Combat Outpost Payne in Helmand Province.

Over the next three years, two modified K-MAX helicopters hauled 4.5 million pounds of cargo—mostly water and food—and established a remarkable reliability record, requiring just about 1.4 hours of maintenance for each hour of flight and costing only about $1,300 an hour of flight time. Most of the missions—some of which took the helicopter as far as 85 miles from its base—were carried out at night, and K-MAX never took a single bullet hole from enemy fire. One of the two helicopters, though, did suffer a “hard landing” after unexpected tailwinds caused its load to oscillate and the pilots on the ground were slow to intervene.

K-MAX, which averaged five or six missions a day, flew itself autonomously between pre-designated waypoints, and relied upon just one Toughbook laptop as its control station for takeoff and landing—as well as a joystick that was already familiar to many Marines: a controller nearly identical to those of a standard Playstation. “You plan the mission, then let the system fly the route,” he says. “All you should be doing is taking off and landing, and life’s good.” After completing the Afghanistan mission, the Marine Corps took those two K-MAX helicopters to Yuma, Arizona, where it continues to use them for testing and development.

Mark L. Bathrick, who since 2005 has headed the Department of the Interior’s Office of Aviation Services, had followed K-MAX’s work in Afghanistan, and in May 2014 asked Lockheed representatives whether the company could deploy the technology on wildland fires. The former Navy test pilot knew the value that such large platforms could bring; he’d spent the end of his career working with uncrewed F-4 Phantom jets, used by the military as live targets and to pioneer risky technologies. The Department of the Interior already had a fleet of piloted K-MAX helicopters in its seasonal firefighting fleet.

Within months, Lockheed pulled together its first domestic firefighting demonstration with the uncrewed K-MAX and followed it up with more complex demos in Idaho in 2015 and the one in Rome in 2016. “We were very happy that the company supported these demonstrations—it was all on their dime,” Bathrick says. Attaching the Bambi bucket was easy enough—crewed K-MAXs regularly use them to fight fires—and since firefighting isn’t all that different from cargo-hauling, the software and sensors needed only a few tweaks to adapt. “They were able to accurately and consistently dip that bucket in a pretty confined dip site, use their software to navigate to the fire, and successfully drop the water. We saw some success, but they were still working to adjust the flight dynamics with the physics of the water coming out. By Boise, we saw some real improvements.”

During the Boise demonstration, dozens of representatives from firefighting agencies watched as Lockheed put a K-MAX through its paces, delivering some 12 tons of water in an hour. A wildland fire to the north even filled the air with smoke, allowing observers to carefully study the difference between the UAV’s infrared cameras and its electro-optical ones.

If the technology continues to advance, it could help revolutionize long-standing firefighting and search-and-rescue practices. “In wildland firefighting, it’s the firefighters on the ground that actually contain and extinguish a fire,” Bathrick says. “It’s not us air guys—just like in a war, it’s the troops on the ground. For the last 80 years of fighting fires, we’ve only been able to support those guys for about eight hours a day.”

He imagines a day when crewed K-MAXs could fly during the day and then, in uncrewed mode, continue flying through the night— particularly valuable because fires are typically most vulnerable overnight, as winds die down, temperatures moderate, and humidity increases.

Flying UAVs around wildland fires also carries an additional benefit. The airspace above a wildland fire is restricted and controlled by the fire boss, who is in charge of the firefighting efforts. The Department of the Interior already has an agreement with the FAA that within those temporary flight restrictions, the Interior can pilot UAVs beyond line-of-sight. “I don’t have to worry about all the things that come with flying an aircraft within the national airspace,” Bathrick says. Eventually the experience in the restricted airspace of a fire may give the FAA insight into integrating UAV operations into less-restricted areas.

Wildland fires have been growing in intensity in recent years, and they pose unique challenges for fliers. Firefighting flights are expensive: upwards of $4,000 an hour for tanker aircraft and upwards of $6,000 an hour for heavy-duty helicopters. The flying is dangerous because the airplanes themselves are often old and balky, and pilots have to fly them aggressively at low altitudes. The flights are limited to daytime hours and low-smoke areas, but even under tight restrictions, they can be highly risky. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one-quarter of all U.S. wildland firefighting fatalities between 2000 and 2013 were aviation-related; 38 aircraft crashes killed 75 firefighters and crew.

An autonomous platform’s ability to provide round-the-clock aerial coverage to major incidents without risking the life of a flight crew could be transformative. Such platforms are already being used for surveillance on large fires; in 2015, a 75-pound Textron drone provided overhead data and images about a fire near Tepee Springs, Idaho, for 18 hours a day for five days.

Colorado’s Center of Excellence for Advanced Technology Aerial Firefighting, a state entity tasked with testing aerial firefighting techniques, has been closely monitoring systems like K-MAX. “The technology is there,” says Garrett Seddon, who oversees the center’s military and UAV integration programs. “They have to hone it in on where they drop and how they drop—but it’s waiting for FAA to catch up.”

Actually, says Melissa Lineberger, director of the Colorado center, today firefighters are more focused on keeping drones out of firefighting areas. During last summer’s fire season out west, hobbyist drone operators looking to make cool YouTube movies repeatedly interfered with aerial firefighting efforts. CalFire, California’s wildfire agency, launched a public education campaign, but Utah adapted a more extreme measure: State law now allows civilian drones over fires to be shot down or jammed and deliberately crashed.

Search-and-rescue is another difficult, sometimes tedious job that drones could transform. SARA’s autonomous search-and-rescue capabilities—on early display during the November demonstration—could help dramatically, particularly if married with swarms of smaller UAVs that could quickly search large areas for lost or injured people.

Yet as technologies like K-MAX, Cormorant, and SARA mature, they’ll certainly become an integral part of firefighting. “We fight fires the same way our parents and grandparents fought fire,” Lineberger says. But that could change quickly. As last winter’s wildfires in Tennessee spread, Lockheed and the government entered emergency discussions about deploying a K-MAX. Ultimately the fires died down before the helicopter could be brought to bear. But another opportunity for real-world experience will come about all too soon.