World War I Letters Show Theodore Roosevelt’s Unbearable Grief After the Death of his Son

A rich trove of letters in the new book “My Fellow Soldiers” tells the stories of generals, doughboys, doctors and nurses, and those on the home front

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/0e/c90e2d14-445d-43e4-8d52-0185208f1ba2/27quentinrooseveltcrop.jpg)

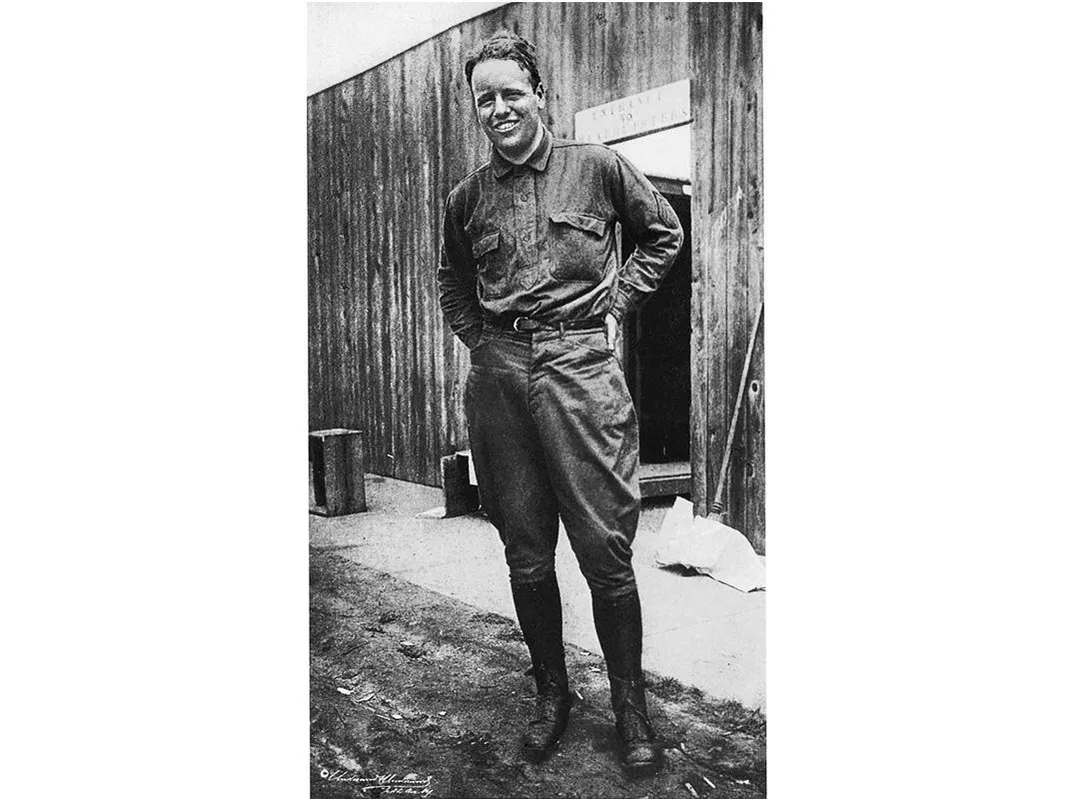

Andrew Carroll, founder of the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University), an archive of wartime letters from every U.S. conflict, is the author of the new book My Fellow Soldiers: General John Pershing and the Americans Who Helped Win the Great War, a vivid retelling of the American experience in World War I. The book features many little-known and previously unpublished journals and letters, including ones by a young man, incorrigibly fearless and much loved by his family, who died in a fiery plane crash behind enemy lines on July 14, 1918. He was President Theodore Roosevelt’s son Quentin. In an excerpt from Carroll’s book, the young Roosevelt’s last days are told in letters from friends and family.

“I am now plugging along from day to day, doing my work, and enjoying my flying,” 21-year-old Quentin Roosevelt wrote to his fiancée, Flora Whitney, from Issoudun, France, on December 8, 1917. Quentin was the youngest son of former president Theodore Roosevelt, and his letters exuded the same enthusiasm that the Lafayette Escadrille pilots had expressed years before. “These little fast machines are delightful,” he wrote, referring to the Nieuport 18s they used.

You feel so at home in them, for there is just room in the cockpit for you and your controls, and not an inch more. And they’re so quick to act. It’s not like piloting a lumbering Curtis[s], for you could do two loops in a Nieuport during the time it takes a Curtis[s] to do one. It’s frightfully cold, now, tho’. Even in my teddy-bear,—that’s what they call these aviator suits,—I freeze pretty generally, if I try any ceiling work. If it’s freezing down below it is some cold up about fifteen thousand feet. Aviation has considerably altered my views on religion. I don’t see how the angels stand it.

Roosevelt had been drawn to airplanes since he was eleven years old. In the summer of 1909, he was with his family vacationing in France when he watched his first air show. “We were at Rheims and saw all the aeroplanes flying, and saw Curtis[s] who won the Gordon Bennett cup for the swiftest flight,” Roosevelt wrote to a school friend, referring to aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss. “You don’t know how pretty it was to see all the aeroplanes sailing at a time.” (Ironically, when Roosevelt later learned to fly, his least favorite planes were those built by Curtiss, whose name he also regularly misspelled. Roosevelt had suffered a serious back injury in college, and he found the Curtiss planes extremely uncomfortable.)

Roosevelt had started his flight training at the age of 19 in Mineola, New York, where there was an aviation school less than half an hour from his family’s home in Oyster Bay. Graduated as a lieutenant, he was assigned to Issoudun. Roosevelt was an experienced mechanic—he grew up tinkering with broken-down motorcycle and car engines—and along with his flight duties, he was put in charge of maintaining and repairing more than 50 trucks. He was also given supply duties and, because he was fluent in French, frequently asked to serve as an interpreter for senior American officers when they had to converse with French officials.

Roosevelt earned the admiration of the enlisted men and junior officers for an incident involving a clash with an obstinate captain who wouldn’t give the men desperately needed winter boots. “When, as flying cadets under the command of Lieutenant Quentin Roosevelt,” a fellow lieutenant named Linton Cox recalled to a newspaper back in the States, “we were receiving training at Issoudun in the art of standing guard in three feet of mud and were serving as saw and hatchet carpenters, building shelters for the 1,200 cadets who were waiting in vain for machines in which to fly, affairs suddenly reached a crisis when it was discovered that the quartermaster refused to issue rubber boots to us, because the regular army regulations contained no official mention or recognition of flying cadets.”

Cox went on to relate how appeal after appeal was rejected, and the men were starting to get sick, standing for hours in freezing mud up to their knees. Roosevelt decided to approach the captain, who, in Cox’s words, “was a stickler for army red tape, and did not have the courage to exercise common sense,” and requested that the soldiers be given the proper boots. When Roosevelt was refused as well, he demanded an explanation. Infuriated by the young lieutenant’s impertinence, the captain ordered him out of his office. Roosevelt wouldn’t budge.

“Who do you think you are—what is your name?” the captain demanded.

“I’ll tell you my name after you have honored this requisition, but not before,” Roosevelt said. He wasn’t afraid of identifying himself; he simply didn’t want there to be even the appearance of expecting favoritism because of his famous last name.

The confrontation escalated, and, according to Cox, “Quentin, being unable longer to control his indignation, stepped up and said, ‘If you’ll take off your Sam Browne belt and insignia of rank I’ll take off mine, and we’ll see if you can put me out of the office. I’m going to have those boots for my men if I have to be court-martialed for a breach of military discipline.’”

Two other officers who overheard the yelling intervened before any fists were thrown, and Roosevelt stormed out of the office and went directly to the major of the battalion. He explained the situation, and the major agreed with Roosevelt and assured him that the boots would be provided.

“Roosevelt had hardly left the major’s office when the quartermaster captain came in and stated that there was a certain aviation lieutenant in camp whom he wanted court-martialed,” Cox recounted.

“Who is the lieutenant?” asked the major.

“I don’t know who he is,” replied the captain, “but I can find out.”

“I know who he is,” said the major. “His name is Quentin Roosevelt, and there is no finer gentleman nor more efficient officer in this camp, and from what I know, if anyone deserves a court-martial you are the man. From now on you issue rubber boots to every cadet who applies for them, armed regulations be damned.”

The boots were immediately issued, and the cadets were loud in their praise of Lieutenant Roosevelt.

Apologizing to his family and fiancée that his letters were “unutterably dull and uninteresting,” Roosevelt explained that he remained mired in bureaucratic and official duties. (He had also suffered from recurring pneumonia and a case of the measles, information he withheld from his family until he had fully recovered.) Disorganization and delays plagued the entire Air Service; in a January 15, 1918, letter to his mother, Roosevelt railed against the “little tin-god civilians and army fossils that sit in Washington [and] seem to do nothing but lie” about how well things were supposedly progressing in France. “I saw one official statement about the hundred squadrons we are forming to be on the front by June,” he wrote.

“That doesn’t seem funny to us over here,—it seems criminal, for they will expect us to produce the result that one hundred squadrons would have.” Currently, there were all of two squadrons at Issoudun. Congress had appropriated funding to build 5,000 American warplanes, but by early 1918, U.S. manufacturers were unable to construct anything comparable to what either the Allies or the Germans had developed.

Without even checking with the War Department, General Pershing summarily ordered several thousand planes from the French, at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“There’s one good thing about going to the front,” Roosevelt continued in his letter to his mother. “I shall be so busy worrying about the safety of my own neck that I shan’t have time to worry about the way the war is going.” He also felt an obligation, as a Roosevelt, to be in the fight. “I owe it to the family—to father, and especially to Arch and Ted who are out there already and facing the dangers of it.” Less than a month later, Roosevelt was offered a plum assignment in Paris to fly planes from their factories in the capital out to their designated airfields throughout France. Although not dangerous, the job was, in fact, critical, and it offered the thrill of flying different types of aircraft, with the added benefit of living in posh quarters. Roosevelt turned it down.

Another two months passed, and Roosevelt was still stuck at Issoudun. There was, however, some good news to report. “Things are beginning to hum here at school,” he wrote to his mother on April 15, 1918. “For one thing, we hear that they are not going to send any more pilots over here from the states for the present, which is about the first sensible decision that they have made as regards the Air Service. As it is they must have two thousand pilots over here, and Heavens knows it will be ages before we have enough machines for even half that number.”

*****

“I am now a member of the 95th Aero Squadron, 1st Pursuit Group,” Quentin Roosevelt proudly announced to his mother on June 25, 1918. “I’m on the front—cheers, oh cheers—and I’m very happy.”

On July 11, he sent her a more detailed letter describing his experiences. “I got my first real excitement on the front for I think I got a Boche,” Quentin wrote.

I was out on high patrol with the rest of my squadron when we got broken up, due to a mistake in formation. I dropped into a turn of a vrille [i.e., a dive]—these planes have so little surface that at five thousand you can’t do much with them. When I got straightened out I couldn’t spot my crowd any where, so, as I had only been up an hour, I decided to fool around a little before going home, as I was just over the lines. I turned and circled for five minutes or so, and then suddenly,—the way planes do come into focus in the air, I saw three planes in formation. At first I thought they were Boche, but as they paid no attention to me, I finally decided to chase them, thinking they were part of my crowd, so I started after them full speed. . . .

They had been going absolutely straight and I was nearly in formation when the leader did a turn, and I saw to my horror that they had white tails with black crosses on them. Still I was so near by them that I thought I might pull up a little and take a crack at them. I had altitude on them, and what was more they hadn’t seen me, so I pulled up, put my sights on the end man, and let go. I saw my tracers going all around him, but for some reason he never even turned, until all of a sudden his tail came up and he went down in a vrille. I wanted to follow him but the other two had started around after me, so I had to cut and run. However, I could half watch him looking back, and he was still spinning when he hit the clouds three thousand meters below. . . .

At the moment every one is very much pleased in our Squadron for we are getting new planes. We have been using Nieuports, which have the disadvantage of not being particularly reliable and being inclined to catch fire.

Three days later, Quentin was surrounded by German fighters and, unable to shake them, was shot twice in the head. His plane spun out of control and crashed behind enemy lines.

News of Quentin’s death was reported worldwide. Even the Germans admired that the son of a president would forgo a life of privilege for the dangers of war, and they gave him a full military burial with honors.

General Pershing, who had lost his wife and three little girls in a house fire in August 1915, knew Quentin personally, and when his death was confirmed, it was Pershing’s turn to send a letter of sympathy to his old friend Theodore Roosevelt: “I have delayed writing you in the hope that we might still learn that, through some good fortune, your son Quentin had managed to land safely inside the German lines,” Pershing began.

Now the telegram from the International Red Cross at Berne, stating that the German Red Cross confirms the newspaper reports of his death, has taken even this hope away. Quentin died as he had lived and served, nobly and unselfishly; in the full strength and vigor of his youth, fighting the enemy in clean combat. You may well be proud of your gift to the nation in his supreme sacrifice.

I realize that time alone can heal the wound, yet I know that at such a time the stumbling words of understanding from one’s friends help, and I want to express to you and to Quentin’s mother my deepest sympathy. Perhaps I can come as near to realizing what such a loss means as anyone.

Enclosed is a copy of his official record in the Air Service. The brevity and curtness of the official words paint clearly the picture of his service, which was an honor to us all.

Believe me, Sincerely yours, JPP

“I am immensely touched by your letter,” Roosevelt replied. He well remembered the trauma that Pershing himself had endured before the war. “My dear fellow,” Roosevelt continued, “you have suffered far more bitter sorrow than has befallen me. You bore it with splendid courage and I should be ashamed of myself if I did not try in a lesser way to emulate that courage.”

Due to Roosevelt’s status as a former president, he received countless letters and telegrams from other heads of state, as well as total strangers, offering their sympathy for the family’s loss. Roosevelt usually responded with a short message of appreciation, but there were two letters of condolence, one to him and one to Mrs. Roosevelt, from a woman named Mrs. H. L. Freeland, that particularly touched them, and on August 14, 1918, exactly a month after Quentin was killed, Theodore sent back a lengthy, handwritten reply.

Last evening, as we were sitting together in the North Room, Mrs. Roosevelt handed me your two letters, saying that they were such dear letters that I must see them. As yet it is hard for her to answer even the letters she cares for most; but yours have so singular a quality that I do not mind writing you of the intimate things which one cannot speak of to strangers.

Quentin was her baby, the last child left in the home nest; on the night before he sailed, a year ago, she did as she always had done and went upstairs to tuck him into bed—the huge, laughing, gentle-hearted boy. He was always thoughtful and considerate of those with whom he came in contact. . . .

It is hard to open the letters coming from those you love who are dead; but Quentin’s last letters, written during his three weeks at the front, when of his squadron on an average a man was killed every day, are written with real joy in the “great adventure.” He was engaged to a very beautiful girl, of very fine and high character; it is heartbreaking for her, as well as for his mother; but they have both said that they would rather have him never come back than never have gone. He had his crowded hour, he died at the crest of life, in the glory of the dawn. . . .

Is your husband in the army? Give him my warm regards and your mother and father and sister. I wish to see any of you or all of you out here at my house, if you ever come to New York. Will you promise to let me know?

Faithfully yours, Theodore Roosevelt

After Quentin’s death, the once boisterous former president was more subdued, and his physical health declined rapidly. In his final days, Roosevelt often went down to the family’s stables to be near the horses that Quentin as a child had so loved to ride. Lost in sorrow, Roosevelt would stand there alone, quietly repeating the pet name he’d given his son when he was a boy, “Oh Quenty-quee, oh Quenty-quee . . .”

The Roosevelts decided to leave Quentin buried in Europe, but they did retrieve the mangled axle from his plane, which they displayed prominently at their home in Oyster Bay.

MY FELLOW SOLDIERS: General John Pershing and the Americans Who Helped Win the Great War by Andrew Carroll, is to be published on April 4th by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Andrew Carroll. Carroll is also a historical consultant to the PBS film, “The Great War,” about WWI, and in April, Carroll will launch as well the “Million Letters Campaign,” in which he will travel the country encouraging veterans and troops to share their war letters with the Center for American War Letters to be archived for posterity.

“My Fellow Soldiers: Letters From World War I” is on view at the National Postal Museum through November 29, 2018.