Top Carnivores Help Shape Nearly Every Aspect of Their Environment

From controlling other animals’ numbers to affecting carbon storage, the predators’ vital roles in ecosystems justify their conservation, scientists say

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/7b/4f7b89c6-da05-4630-a5b3-b8bd7958c9d7/wolf.jpg)

Humans have had a long, contentious history with the other large creatures that share the planet. We nearly pushed the American bison into extinction due to overhunting, while the Western black rhino was given no such second chance--it went extinct in 2011. These herbivorous victims were singled out for use as trophies and meat, however, not becuase we perceived them as direct threats. On the other hand, our relationship with top-level carnivores--such as big cats, wolves and bears is fraught with an extra layer of tension, thanks to the fact that these animals are sometimes considered man-eaters (whether fairly or not) and perceived as competing with us for food and space.

These perceptions have led, in some cases, to sustained hunts for these carnivores, from the extermination of wolves in the U.S. and Europe, to retaliatory killing of tigers and lions in Asia and Africa (pdf), respectively. But targeting these predators is now catching up to us. A new paper published in Science by an international team of researchers reveals the central role that top carnivores play in shaping nearly every aspect of an ecosystem, from the number and types of animals that live there, to the plants that grow there, to the diseases that break out. Across the world, top carnivores, they found, stabilize ecosystems, keeping environmental elements in balance and making sure no single creature hijacks the system.

To reach these findings, the authors analyzed how the 31 largest mammalian carnivores around the world affect their ecosystem. The carnivores hailed from five different families and included animals such as wolves, wild dogs, dingo, tigers, lions, cheetahs, jaguars, pumas, Eurasian lynx, sea otters, leopards, bears and hyenas. The species they selected were distributed across continents (except Antarctica), although most of the diversity was concentrated in Africa and Asia. About three-quarters of those species are currently suffering population declines, and 61 percent are listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as threatened.

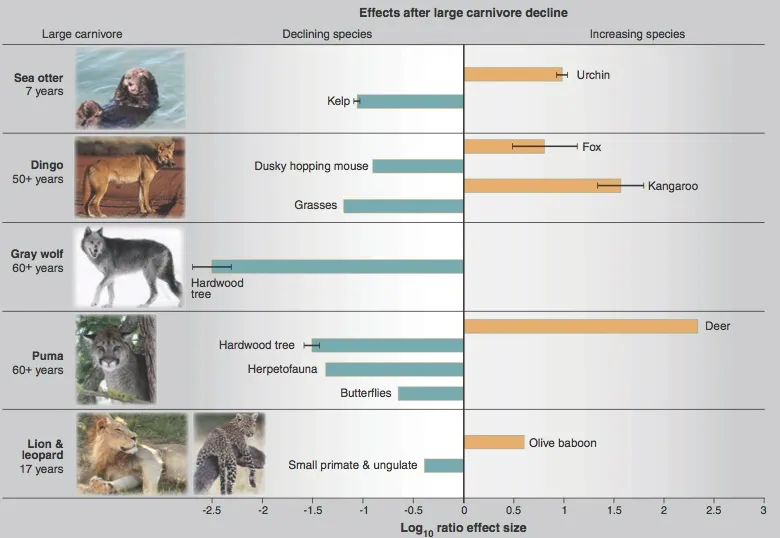

To figure out what ecological role these animals play in their communities, they first searched through scientific literature for confirmed impacts caused by predator loss or reintroduction to an area. Lions, for example, occupy just 17 percent of their historic range, while leopards occur in about 65 percent. When lions and leopards disappeared from parts of West Africa, studies show that baboon populations shot up. Those ravenous primates, in turn, began eating up everything in their path, causing other primates and mammals to decline. Reports show that the baboons also took to raiding crops, resulting in some families pulling their kids out of school and sticking them in field to keep a constant guard against the monkeys.

In Europe, the Eurasian lynx has disappeared from almost all of its historic range. When Finland recently reintroduced it, red fox populations went down, which triggered an increase of native forest grouse and mountain hares. Likewise, as sea otter populations can make or break an ecosystem, turning it from a sea urchin-covered mess to a diverse, healthy kelp forest. “As sea otter populations recover and decline, shifts between the kelp-dominated and urchin-dominated conditions can be abrupt,” the authors write. Humans win when there’s more sea otters around, too: kelp forests soften the impact of waves and currents that whip through coastal areas.

Perhaps the most well documented example of a top carnivore’s impact on the ecosystem, however, are grey wolves. As the wolves were killed off, local deer populations “irrupted,” the authors write, shifting forested areas into grasslands as the deer ate every green thing in their path. As the habitat changed, so too did the species of birds and small mammals that lived there. After removing wolves from much of their environment throughout the U.S., Mexico and Europe, people finally decided it might be a good idea to give the animals a break and allow their populations to recover somewhat. Prior to allowing the wolves to come back, deer populations in North America and Europe were around six times higher than after the predator’s return. Since the wolves come back to Yellowstone, the national park has regained some of its formerly lost forest stands, which provide a home for other native species as well as store more carbon, which helps to offset climate change.

Here, the authors visually depict the environmental changes that occurred when various large carnivores disappeared. The years those animals were missing from the environment is written on the far left. The species declines caused by the carnivores’ disappearance are in blue, while increasing species are in orange:

Due to their cascading effects throughout an environment, top carnivores also play a role in carbon sequestration and disease control, the authors report.

"We say these animals have an intrinsic right to exist, but they are also providing economic and ecological services that people value," William Ripple, a professor at Oregon State University and lead author of the study, said in a statement.

This study, the authors warn, only skims the surface of possible repercussions that stem from top carnivore loss. In the future, as populations of these animals decline, or species are lost, “we should expect surprises, because we have only just begun to understand the influences of these animals in the fabric of nature,” they write.

The team calls for more research to better understand the essential role top carnivores play. But conservation to protect these animals, they point out, is even more urgently needed. This includes not only protecting their habitats but also facilitating peaceful co-existence with nearby humans.

“Many of these animals are at risk of extinction, either locally or globally,” Ripple said. “And, ironically, they are vanishing just as we are learning about their important ecological effects."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)