Tracking Frackers From the Sky

Citizen scientists eyeing Pennsylvania’s natural gas drillers in aerial images may help determine if there is a link between fracking and certain illnesses

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/d5/6ed5e6ca-1ce7-4956-9539-3ab9b9f7d4af/42-27443900.jpg)

Ever since the natural gas boom took off in Pennsylvania in 2006, some people living near the drilling rigs have complained of headaches, gastrointestinal ailments, skin problems and asthma. They suspect that exposure to the chemicals used in the drilling practice called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, triggers the symptoms. But there’s a hitch: the exact locations of many active fracking sites remain a closely guarded secret.

Brian Schwartz, an environmental epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and his colleagues have teamed up with Geisinger Health System, a health services organization in Pennsylvania, to analyze the digital medical records of more than 400,000 patients in the state in order to assess the impacts of fracking on neonatal and respiratory health.

While the scientists will track where these people live, says Schwartz, state regulators cannot tell them where the active well pads and waste pits are located. Officials at Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) say that they have simply never compiled a comprehensive list.

So the Johns Hopkins researchers turned to a small nonprofit called SkyTruth, which scrutinizes satellite and other aerial imagery to figure out what is happening down here on Earth. The scientists traveled to the group’s headquarters in West Virginia in September 2013 to ask SkyTruth to help them locate Pennsylvania’s fracking wastewater ponds.

Fracking is a process in which a slurry of water mixed with sand and chemical lubricants is pumped underground at high pressure to shatter shale rock and release the natural gas imbedded within it. A portion of the spent fracking liquid shoots back up the well bore and needs to be disposed of. This “flowback" is laden with up to 40 different industrial chemicals and is often radioactive from its exposure to elements, such as radium and thorium, underground. While some of the tainted water is treated and then discharged into local rivers and streams, much of it gets stored in large plastic-lined impoundment ponds. The ponds waft a noxious chemical odor that may be responsible for respiratory problems in nearby residents.

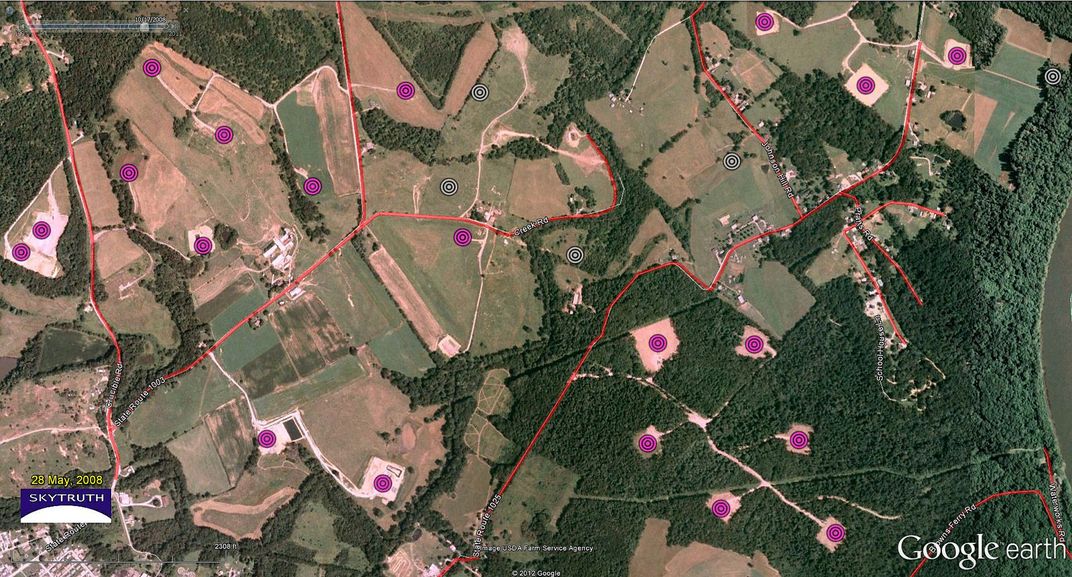

To pinpoint the location of these ponds, SkyTruth launched a project called FrackFinder. They enlisted more than 200 volunteers in public meetings and on social media from as far away as Japan, who have collectively spent thousands of hours poring over satellite images of Pennsylvania’s bucolic landscape. SkyTruth trained its recruits online and with specially designed apps to distinguish regularly-shaped waste ponds from natural ponds and wetlands. Ten different volunteers examined each image to ensure the accuracy of the data.

SkyTruth just released its crowdsourced map, which shows over 500 fracking ponds in Pennsylvania, up from a mere 11 located in photographs taken in 2005.

SkyTruth is the brainchild of John Amos, a geologist who began his career analyzing satellite images to advise oil and gas companies where to drill. He noticed that the photos revealed a lot more than just promising geological formations. Amos saw oil slicks in the Gulf of Mexico and off the coast of Australia and massive clear cuts hacked out of the vast boreal forests of Siberia—deforestation rivaling what is happening in the Amazon in scale.

“What really pushed me over the edge emotionally,” says Amos, “was looking at satellite imagery of western Wyoming, where I got my Master’s degree.” He was shocked to see that an area that had been pristine rangeland when he was going to school during the mid-1980s was, just 10 years later, “a spider’s web of drilling sites, pipelines and access roads.” Public lands had been totally converted for industrial use.

“I wondered why these pictures weren’t on the front pages of the major newspapers of the world,” says Amos. “People need to see this.”

When the first Landsat satellite was launched in 1972, NASA sold single images to interested parties for upwards of $4,000 each. That put the pictures out of reach for all but a few deep-pocketed corporate and academic researchers. Today, the entire Landsat archive of thousands of high-resolution photographs is available free for anyone to download.

This has proven to be a bonanza for citizen science groups like SkyTruth. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, some elected officials claimed that “not one drop of oil” had been spilled from the offshore infrastructures in the Gulf. But SkyTruth used the latest radar-satellite images to document an oil slick covering more than 270 square miles that emanated from known drilling platforms and pipelines—a finding later confirmed by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Five years later, in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon explosion in the Gulf, SkyTruth estimated, based on the size of the visible oil plume, that the spill was at least 20 times as large as what BP was claiming at the time.

SkyTruth is the first environmental whistleblower to focus exclusively on sleuthing from the sky. The group’s motto is: “If you can see it, you can change it.” They distribute aerial photographs of everything from mountaintop removal to oil sands development and urban sprawl to the press and environmental groups, and share them with the public through social media. Revealing the ecological destruction that humans are wreaking on the planet, however, is only one aspect of the group’s mission. They also want to get people more engaged.

“Our volunteers get to see what fracking in their area actually looks like. It is an informational experience,” says David Manthos, director of the FrackFinder project. “For some, SkyTruthing may be a stepping stone to writing their elected officials, or putting on waders and going out in the field to take water quality measurements.”

Brent Newman, a graduate student in geography at the University of Maryland, volunteered and was stunned to see how fracking has transformed large swaths of rural Pennsylvania into industrial landscapes. “Just to see the sheer number of fracking ponds was alarming,” says Newman. Motivated by this eye-opening experience, he is currently conducting his own independent research on deforestation due to hydraulic fracturing for his Master’s degree.

People like Brent Newman are part of a growing movement of citizen scientists who are stepping in where government and the shale-gas industry have fallen short, according to Kirk Jalbert, a doctoral student at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Jalbert, who has been doing research on several water-monitoring groups in Pennsylvania, distinguishes between two very different types of citizen science.

“You might get an academic researcher who asks 100 or 200 people to parse through data and tell him where DNA strands connect,” says Jalbert. “But that doesn’t produce engaged citizens, it teaches people to connect dots. Producing engaged citizens means having people frame and pursue the questions that they want answered.”

Questions like, how is fracking affecting my water supply?

“The majority of the participants [in the fracking monitoring groups] don’t see themselves as activists,” according to Jalbert. “People tell me, ‘you know I grew up in this county, I swam in these streams, my kids swim in these streams, there’s a gas pad that’s going in on the ridge up there, and I want to make sure that they don’t screw up my water.’”

Now that the SkyTruth fracking map is completed, the Johns Hopkins epidemiological study is gearing up. They are now checking whether asthma patients who live near natural gas sites have suffered exacerbations of their illness. The researchers hope to have preliminary results on this within the next few months.

For SkyTruth, the investigation of fracking in Pennsylvania is only the beginning. The group recently launched a partnership with Walsh University in North Canton, Ohio, where volunteers will be mapping the “ecological footprint” of shale drilling, or how much forest was cleared and agricultural land converted to industrial use. Pending adequate funding, Texas— with 6,000 oil and gas fracking wells, the largest number of any state—is on their radar to tackle next.

“It’s a big planet,” says Amos. But looked at from above, we come to recognize it as home. “Time and again, we've seen how pictures motivate people to pay attention, to care about a place, and—hopefully—to take action if they see something they don't like.”