These 3D-Printed Objects Can Turn Any Color You Want

MIT researchers hope a process that uses a special photochromic dye to change an object’s color in response to light will one day reduce waste

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/62/5462ef7c-6e12-4094-8a8a-68498926cb3d/colorfab_items_of_different_colors_with_activation_areas_-_credit_mit_csail.jpg)

Imagine you’re in IKEA, looking for a plastic kitchen stool. You find one, but—darn—it’s turquoise, which just doesn’t match your home color scheme. No problem. You tell a salesperson, who pushes a button and—bingo!—the chair changes color to the exact lavender of your KitchenAid mixer.

This sci-fi scenario is several steps closer to reality now, thanks to new research from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). Researchers at the lab have developed a method of changing the color of a 3D-printed object—after the object’s been printed.

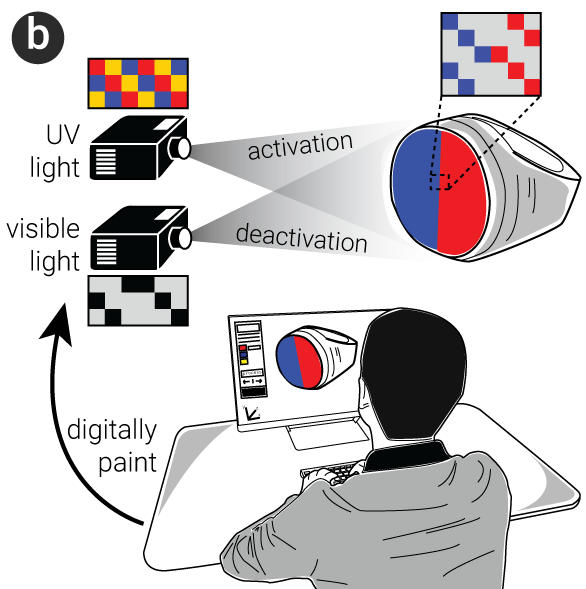

The plastic objects are printed using a special ink that changes color in response to light. UV light activates the colors you want, while visible light deactivates the ones you don’t. Users control the process pixel by pixel through a digital interface. The color changing takes about 23 minutes.

The process, which the team calls “ColorFab,” was described in a recent paper, to be presented at the ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Montreal this April.

“We use a UV light to change the pixels on an object from transparent to colored, and then a regular office projector to turn them from colored to transparent,” explains Stefanie Mueller, senior author and professor at CSAIL.

Since there weren’t any 3D printable photochromic inks in existence, CSAIL had to create its own. The ink has three parts: a base dye, a photo-initiator, and light-adaptable or “photochromic” dyes. The photochromic dyes activate the colors in the base dye, which is then hardened by the photo-initiator.

“We were surprised that we were able to develop our own custom ink that was able to perform as well as it did at recoloring,” Mueller says.

While systems for changing objects’ colors exist—for example, Japanese researchers created a “photochromic carpet” that allowed users wearing UV lights on the soles of their shoes to create colored footprints on a carpet dyed with color-changing ink—these have all been single-color. Color-change processes relying on thermochromic (heat sensitive) ink exist too, but they are also single-color. Some of the same researchers behind the photochromic carpet did create a multi-color change system using painted photochromic pixels, but it was only used on paper, not on 3D objects.

Mueller imagines the ColorFab technology being used in advertising, allowing companies to print billboards and then adjust them to match the surrounding color schemes of the spaces where they’re installed. It could also allow users to customize products in real-time.

“For example, stores could re-color an article of clothing or accessory so that a shopper can see if they like it better in that shade,” Mueller says.

In theory, the technique could help reduce waste by making it unnecessary to buy multiple versions of items. Instead of having bracelets in every color of the rainbow, you could simply program the one you have to match your current outfit. Instead of keeping several sets of kitchenware to go with different dinner themes, you could set your plates to turn bright yellow to contrast with your signature ratatouille.

The team says they hope to bring the process to well under the current 23 minutes by using stronger lights or more light-adaptable dyes, and to make the colors sharper. They also eventually hope to expand the technique to materials beyond plastic.

As for the time frame? Mueller’s not sure when color-change products might be headed to your local superstore. So think hard about that neon green tea kettle before you buy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)