The Tragic Irony of the U.S. Capitol’s Peace Monument

An unfinished Civil War memorial became an allegory for peace—and a scene of insurrection

:focal(749x335:750x336)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/71/dc715c0f-0ef9-43e3-a2c5-08ffd9b77171/peacememorial10.jpg)

After the storming of Congress in early January, some rioters were apparently surprised to learn that the mere “traffic circle” where they were being arrested was, in fact, the Peace Monument, and part of U.S. Capitol grounds. Mostly unnoticed on ordinary days, the ghostly, eroded statue at the end of Pennsylvania Avenue became a focal point in the news footage of the violent afternoon and remains an enigmatic emblem of its aftermath.

The Peace Monument, strangely enough, got its rocky start as a war memorial, in honor of lost Union sailors and marines. It was conceived by Adm. David Dixon Porter, a famous commander, who intended it for the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, where he served as superintendent. He personally raised funds and, in 1871, commissioned the sculpture, even sketching out his own vision—and taking fire for it. Porter “knows more about the high seas than he does about high art,” one critic sniped.

An amalgam of classical allusions and Victorian funerary motifs, the sculpture remains something of a puzzle to modern eyes. “It’s a mishmash monument,” says Elise Friedland, a George Washington University scholar, who is researching a book about the capital city’s classical art and architecture.

At the top, which reaches around 44 feet, is the bookish muse of History, consulting a tome inscribed “they died that their country might live.” Another female figure, believed to be Grief, cries on History’s shoulder. Below gloats Victory; at her feet are cherubic versions of Mars and Neptune, toying with sword and trident.

And where is the figure of Peace? Tacked onto the back of the sculpture like an afterthought.

Swept away by passion for his memorial project, Porter waited until his final fundraising efforts had all but capsized to share his plans with Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. The two men had a contentious relationship—Welles “served his country in its darkest hour with fidelity and zeal, if not with conspicuous ability,” Porter once wrote—and Welles vetoed Porter’s plan. The Naval Memorial, as it was called, would not sail to Annapolis after all, nor be installed at the academy. But Congress scrounged up funds and found a second-best spot, at the foot of Capitol Hill.

Sculpted by the prolific Maine native Franklin Simmons at his studio in Rome, the star-crossed monument was shipped to the District of Columbia in pieces and finished in 1877. The statue of Peace was in fact a last-minute addition, and faces the Capitol in an inexplicably topless state. (“Why is Peace naked?” Friedland wonders.) Peace was perhaps a political compromise, added to mollify former Confederates in Congress who weren’t eager to support a tribute to the Union cause. Porter shot off a note to the Architect of the Capitol: “If this statue don’t make members of Congress feel peaceful I don’t know what will.” A novelty in a city full of war memorials, this makeshift peace shrine was not formally dedicated or even quite finished; the design called for bronze dolphins that still haven’t surfaced.

Made of Carrara marble, a material as vulnerable to the elements as peace itself, the monument has not handled acid rain and pollution well. The human faces have blurred. A marble dove at Peace’s feet flew the coop long ago. Body parts have snapped off and been replaced. Making sense of the elaborate artwork has never been straightforward. “This is the issue with these allegorical monuments,” says University of Pittsburgh art historian Kirk Savage. “They can kind of mean anything.” It’s inevitable, he says, that the monument would “be appropriated for other reasons and uses.” (Besides, he adds, “it seems pretty easy to climb.”) In 1971, Vietnam War protesters scaled the monument and rested with flags at the top, looking like statues themselves. During the insurrection this past January, somebody slung a scarf around Victory’s neck and a guy wearing a cowboy hat and holding a bullhorn loomed over baby Mars, god of war.

Contemporary peace memorials tend toward radical simplicity—an installation outside Oslo City Hall, where the Nobel Peace Prize is handed out, is a smile-shaped arc. But some artists see immense power in antique statuary. Krzysztof Wodiczko, who works with video projections and has beamed the faces of traumatized soldiers onto the Lincoln Memorial in New York City’s Union Square Park, says the Peace Monument’s human forms have a hold on us. “We have a special relationship to those statues. We identify with them. We animate them without knowing who they are. We want them to witness what we want to say. Sometimes we sit on their shoulders and put flags in their hands.”

In the days after the Capitol riot, a new face appeared at the Peace Monument: Brian Sicknick, the Capitol Police officer who died after the mob attack. Mourners left photographs of him beside cut flowers and American flags. A cardboard sign said, “Rest in Peace.”

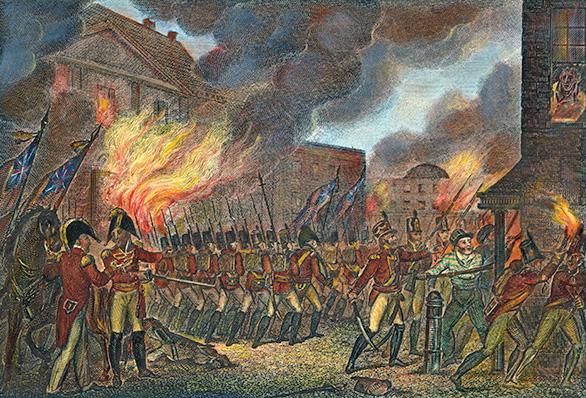

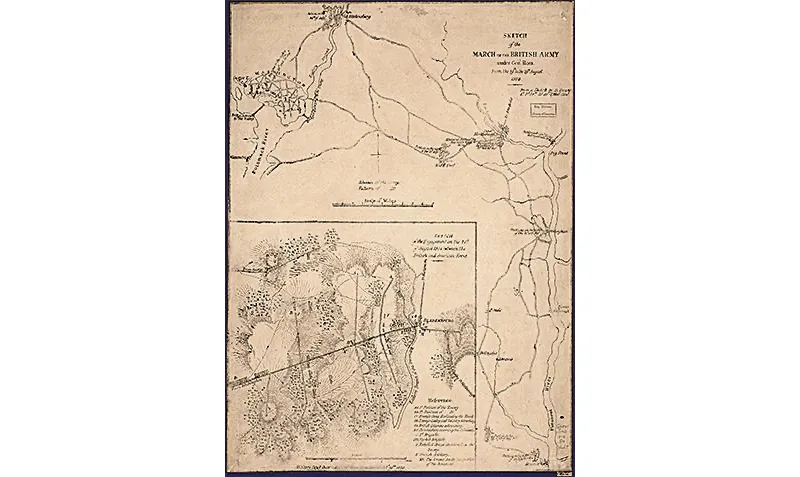

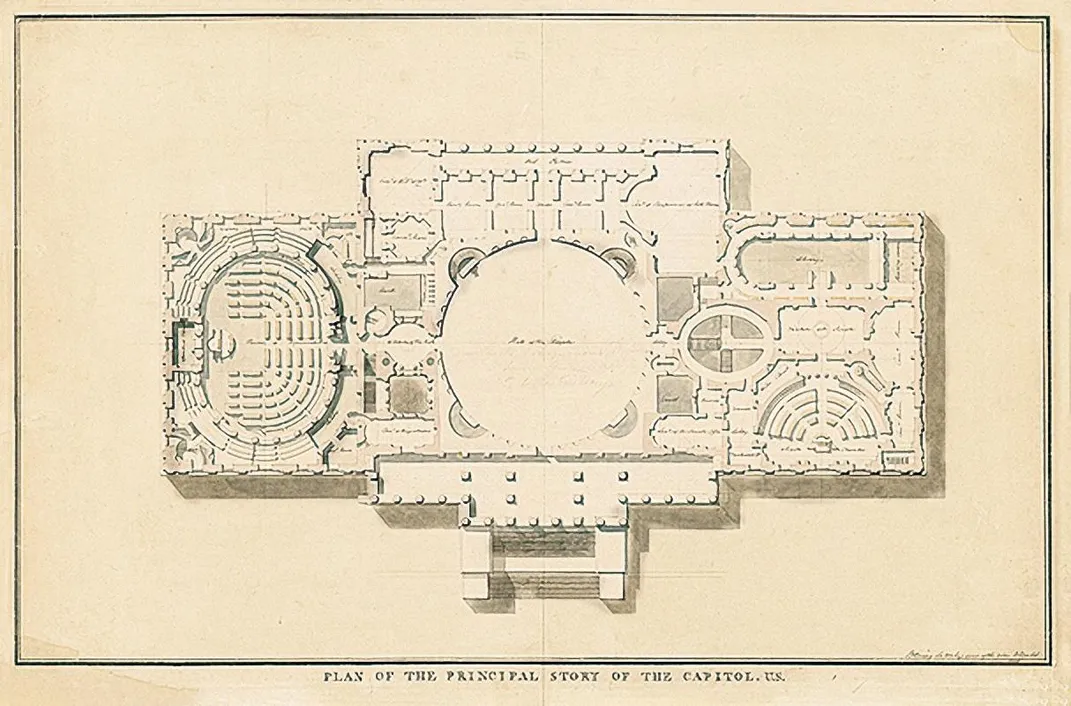

Attack on the Capitol

British troops torched the building during a chaotic 26 hours in the War of 1812. But the symbol of democracy stood

By Ted Scheinman

Editor's note, April 19, 2021: This story has been updated to clarify the circumstances of U.S. Capitol police officer Brian Sicknick's death. He died after suffering two strokes after the attack on the Capitol; it is unclear the degree to which his health was affected by his engagement with the mob.