A Fresh Look at the Boston Massacre, 250 Years After the Event That Jumpstarted the Revolution

The five deaths may have shook the colonies, but a new book examines the personal relationships forever changed by them too

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/a9/93a97057-f628-4de7-adc7-c2ca0f68c4ac/boston_massacre_high-res.jpg)

Tensions in the American colonies were rising. For one, the British Parliament’s 1765 Stamp Act required colonists to pay an extra fee for every piece of printed paper. And the 1767 Townshend Act imposed taxes on imported goods such as china, glass, lead, paint, paper and tea. Resentful toward their lack of representation in Parliament and desirous of the same rights as their fellow British subjects, the colonists agitated for relief from the burdensome levies.

In response, George III dispatched roughly 1,000 troops to the Massachusetts town of Boston to curb the colony’s ongoing unrest. The soldiers had been stationed in Ireland for years, some close to a decade, establishing roots and families there. Concerned that this deployment to the American colonies would result in an overflow of needy children draining the resources in Dublin, the British government allowed for hundreds of wives and kids to accompany their husbands and fathers on the 1768 journey.

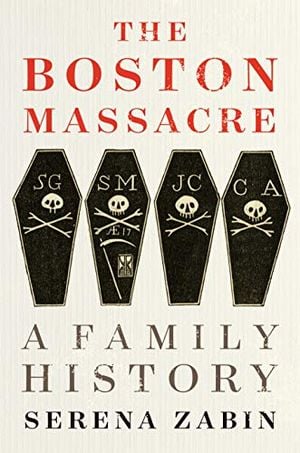

And for the next two years, British and Irish families lived alongside colonists in Boston. They assisted each other when in need and established neighborly relationships, only for those relationships to be irreparably damaged when British troops fired upon Bostonians, killing five, in what became known as the Boston Massacre. In her new book, The Boston Massacre: A Family History, Serena Zabin, a professor of history at Carleton College, explores these lesser-known stories, examining the lives of this community during a tumultuous time in American history.

The Boston Massacre: A Family History

The story of the Boston Massacre—when on a late winter evening in 1770, British soldiers shot five local men to death—is familiar to generations. But from the very beginning, many accounts have obscured a fascinating truth: the Massacre arose from conflicts that were as personal as they were political.

Among the stories Zabin tells is that of Jane Chambers, wife of soldier Mathew Chambers, who while caring for her ailing baby needed a place to perform an emergency baptism. Her husband, a strong opponent of the Stamp Act, pleaded with the minister of the West Church to approve the hurried naming. In the midst of this fraught political battle, the minister and father found common ground. In other instances, British soldiers who didn’t have families found wives in Boston.

The soldiers and Bostonians didn’t always get along, however. The men who served as the official neighborhood lookout often complained that inebriated (“in Licker”) British officers verbally harassed the watchmen. And Bostonian John Rowe found his usual social club flooded with British officers.

What exactly happened on March 5, 1770, when British soldiers fired their rifles and killed five colonists on Boston’s King Street, is a matter of historical debate. The next day, British Captain Thomas Preston turned himself in to the justices of the peace. Throughout the month, in a trial with John Adams as the soldier’s defense attorney, public depositions were held at Faneuil Hall as Bostonians attempted to piece together a coherent story of the events.*

As the case continued, Preston’s reputation shifted from a “benevolent, humane man” in the eyes of Bostonians to “a military criminal,” reflecting how these now severed connections between soldiers and colonists—and Preston’s long-standing relationship with his civilian colleagues—became a rallying cry for the revolutionary Sons of Liberty.

The Boston Massacre uncovers the inevitable human bonds between these two groups, presenting a new angle to an often-told narrative of the American Revolution. On the 250th anniversary of the Boston Massacre, Smithsonian spoke with Zabin about her new book and showing the personal side of a political event.

What role does now-ubiquitous sketch of the Massacre by Henry Pelham play in how people remember the event? Your opening anecdote of the book has Paul Revere crafting his engraving based on his own personal interpretation of the massacre – that of the British as the aggressors. What does that tell us about recounting history?

The Paul Revere engraving is probably the only thing that people really know about the Boston Massacre. Party because it's fabulous, partly because it is one of the very few images from 18th-century America we have that is not a portrait. It's reproduced in every single textbook; we all know it, we've all seen it. But I wanted to show the way in which this picture itself really constitutes its own sleight of hand.

Why does the Boston Massacre matter? Why are we still talking about it today?

We've made it part of our history. There are many incidents that we do and don't remember about the 1770s that are part of the road to revolution. And this is a pretty early one. It's a moment when no one's thinking yet about a revolution. But what's really interesting about the Boston Massacre is that even though no one's thinking about a revolution in 1770, it's really only a couple of years before people take this incident and remake it so that it becomes part of the story. So [the story] itself is able to create part of the revolution, although in the moment, wasn't that at all.

What inspired you to write this very different examination of what happened that day?

It came from happening on just one little piece of evidence from the short narratives that are published the week after the shooting. We have an original copy here at Carleton, and I've been taking my class to see them. But after a few years, I really read the first one for the first time. Someone repeats that he had been hanging out in a Boston house with a [British] soldier's wife and is making threats against Bostonians. And I thought, soldier’s wives? I thought, oh, I don't know anything about soldier’s wives; I've never thought about them. I started pulling on the thread, and then I went to Boston. And my very first day in, I was looking in the church records, and I found the record of a marriage between a [British] soldier and a local woman. I thought, I have a story. Here's a story. So stuff was hidden right there in plain sight, things we all should have been looking at but weren't really paying attention to.

What does this book teach us that's different than other historical accounts of the Boston Massacre?

That politics are human, and the things that divide us are maybe up to us to choose. Whether or not we still continue to live in a world that is divided, in the ways that Revere might have pointed out in that [engraving]. Or, whether we can actually think about and remember the messiness of what it means to be connected to other people and remember that [this bond] is part of our politics.

We think of the American founding as such a guy story, and we spent so much time trying to figure out how all the rest of us who are not John Adams fit into the making of our past. Once I saw the story, I thought I owed it to some of these people whose names we'd forgotten, especially some of the soldier’s wives, to try to tell their story and realize that they're also part of our past.

You write about “the range of people and the complexity of the forces that led to the dramatic moment." I'm curious, how does our understanding of the Boston Massacre change when we learn about it from this perspective of individual families?

When we talk in these political terms about revolution, about the end of the colonial relationship, or anything that we don't really know how to express in a meaningful way, [individual perspectives] help us understand that when an empire breaks up, there are implications for people and families do get torn apart. And this particular way of thinking about the Boston Massacre as a family story helps us see is that we don't always know the political and larger world in which we live. Looking back at this moment through the lens of a family history helps us see these individual stories, but also the larger structures in which they lived that they couldn't recognize themselves.

What has your research revealed to you about history today—the state of history and the way we understand history? How is the past connected with the present?

People love stories. They love to both see themselves and to see the ways in which they are different from people in the past. There's a tension over these 250 years between the past and the present that we're trying to work out as we write about it. There are of course parts of 2020 that are in this book where we wonder, “What is this big world in which I live? What control do I have over the politics that seem to be shaping my world that I can't do anything about?” And I think in that way, many of us feel like these soldiers and their families that are being re-deployed without any ability to say anything about the world that they live in were also making history. And that's the piece that I think is good for us to appreciate—our own lives are part of the past.

What surprised you most when writing?

One is how much of the story was just lying around, waiting for someone to pick up. I felt like every time I turned around, there was more evidence to prove the presence of all of these families, their relationships and the ways in which they were neighbors. I couldn't believe how easy it was to tell this story. I was also really surprised by the enormous numbers of men who deserted the army, more than in other places and other times, and how clear it was that they left to be with locals. They didn't just leave because they hated the army, I thought that was piece of it. But I was really surprised that their connections with locals had this impact on the larger army itself.

What do you hope readers take away from reading the book?

I hope people read it and think sometimes all you have to do is re-adjust your vision a little bit. What happens when we look differently, when we pay attention to things that we don't know. And instead of saying to ourselves, well that's something I don't know and I must be ignorant, to say, “That's something I don't know and it makes me wonder.” So really just keeping our eyes open, whether we're professional historians are not, to be anomalies in the world and thinking how I can make sense of that.

*Editor's Note, March 5, 2020: In an earlier version of this piece, we incorrectly referred to John Adams as Capt. Preston’s defendant. He was his defense attorney.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)