NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

How Norman Granz Revolutionized Jazz for Social Justice

Granz fought Jim Crow America, identifying the potential of jazz music to combat racial inequality.

:focal(188x281:189x282)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Norman_Granz_and_Ella_Fitzgerald_at_microphone-NMAH-AC0584-0000052.jpg)

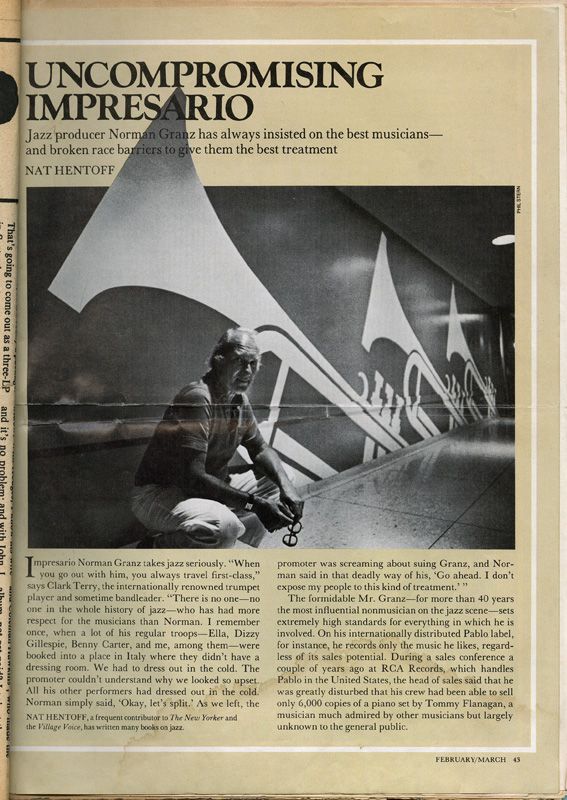

A civil rights protest often invokes the vivid images of sit-ins, boycotts, and marches, but the fight for racial equality took many different forms. One of them was jazz. Norman Granz, a renowned impresario—producer, artist manager, and promoter—recognized the value of jazz, and music, as a tool for social change. Through his Jazz at the Philharmonic concert series, during a time of pervasive racism, Granz employed tactics aimed at desegregating jazz concerts, providing his musicians with equal rights and opportunities, and making jazz accessible to all people.

Firsthand experience with racial discrimination fueled Norman Granz’s desire to end segregation. Born in Los Angeles to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants, Granz was the target of prejudice as a young child. He also witnessed the mistreatment of African Americans on several occasions, including while dating dancer Marie Bryant and realizing that he could not take her to dinner without both of them facing humiliating discrimination. Upon Granz’s return from his service in World War II in the early 1940s, where he observed the oppression of black soldiers, the Los Angeles Sentinel published an account of Granz’s intensified feelings on racial tensions, describing him as “bitter.” The column hints at the deep anger Granz felt about segregation and indicates his shift into a lifetime of activism.

Throughout his career as an impresario and producer, Granz pushed for social change through the method he knew best: jazz. In 1944 Granz launched his Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP) concert series, trademarking the integrated jam session model that brought together artists such as Lester Young, Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, and Ella Fitzgerald. JATP marked a move for jazz from nightclubs to concert halls, and the series generated early commercially produced live recordings that made jazz accessible for everyone. Granz donated the proceeds from the first JATP concert to assist the young defendants in the racially charged Los Angeles “Sleepy Lagoon” murder trial.

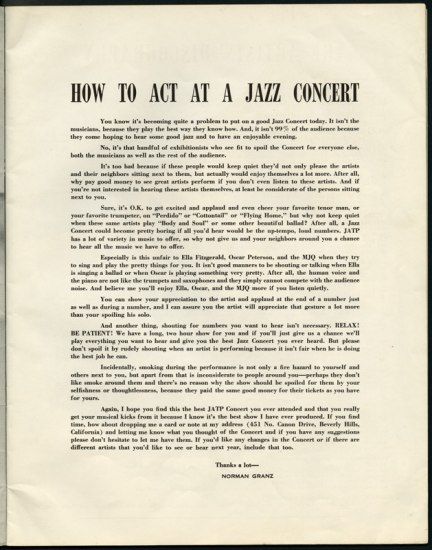

The immense success of JATP and its artists allowed Granz to set his own terms, and he fought hard to make restaurants, hotels, and venues follow them. The rules for the concerts included nondiscrimination clauses in musicians’ contracts, equal pay, and integrated audiences, travel, and accommodations. Granz sometimes paid out of his own pocket to ensure his musicians received first-class treatment. Tad Hershorn’s biography of Granz documents one JATP concert at which a white man complained about sitting next to a black patron. Granz gave the concertgoer his money back but was unrelenting on changing his seat.

“People wanted to see my show,” Hershorn quotes Granz as later saying. “If people wanna see your show, you can lay some conditions down.” Granz recognized the worth of his musicians and the power they had collectively to integrate jazz, and in some ways, contribute to the integration of America.

Norman Granz is often remembered for his artist management of legendary jazz musicians or for being a record producer and label owner, but he should be remembered most for his intense dedication to integration. Granz fought Jim Crow America, identifying the potential of jazz music to combat racial inequality.

Smithsonian Jazz is made possible through leadership support from the LeRoy Neiman Foundation; The Argus Fund; Ella Fitzgerald Charitable Foundation, founding donor of the Jazz Appreciation Month endowment; David C. Frederick and Sophia Lynn; Goldman Sachs; and the John Hammond Performance Series Endowment Fund.