Wingwalker to the Rescue

Air-to-air rapid repair.

:focal(837x598:838x599)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/00/e9008a82-c72f-4291-bdf3-b91744653a21/02-1b_as2021_clarkcockpit2009-0707_live.jpg)

In 1926, I was a freelance pilot flying out of Clover Field in Santa Monica, California. That morning I had enlisted the aid of a friend, Art Jensen, to help service my new Curtiss biplane in anticipation of the weekend passenger business. We had put in gas and oil and checked the Hispano-Suiza engine.

“You grease the wheels while I grab a quick bite,” I said, heading for the airport café. Greasing airplane wheels was a simple process in those days. There were no brakes, no roller bearings—a single bolt and hubcap held the wheel onto the axle. Jensen was a conscientious mechanic, and as he was replacing the hubcap and bolt on the left wheel, he noticed that the bolt threads were damaged and would not accept the nut. Muttering under his breath, he removed the bolt and went to look for a replacement in the hangar.

In the meantime, as I finished my breakfast, I was approached by Frank Clark, a fellow pilot who often flew for Hollywood.

“Your ship okay, Jerry?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied, “just had her completely serviced.’’

“Good,” he said. “Get up here right away, and you can fly the photographer for the airplane change stunt that I’m going to do with Art Goebel and Al Johnson. There’ll be a quick 20 bucks in it for you.”

The airplane change stunt that Frank had referred to was new and elaborate, and the boys had thought it up especially for the Pathé News Reel. I was to carry the photographer into position to record the event.

Back at the flight line, I found my airplane but not Jensen. So I asked one of the other boys to help pull the prop through, and the 180-hp motor soon barked to life.

I taxied up to Clark’s hangar. After quick introductions and an explanation of the stunt, the cameraman climbed into the front seat, and I taxied to the east end of the field and took off.

At that moment, Jensen emerged from the rear of the hangar with a new bolt in his hand. When he saw what was happening, he broke into a run, shouting, “Hey, wait a minute! Stop that plane!”

At 1,500 feet, I banked left, and out of the corner of my eye I saw a flash below and to the left. Banking a little steeper I saw it—a wheel tumbling over and over as it fell to the streets of Santa Monica. My God, it was my landing gear!

My predicament was serious: I was airborne with only one landing wheel in a newly acquired airplane in which I had invested everything. Landings had been made with broken wheels and flat tires, but never without one wheel. The axle’s stub would dig into the ground on landing and flip the airplane onto its back. Even if I cruised around for an hour to use up gas and reduce the fire hazard, the landing would still result in a broken propeller and a damaged wing and vertical fin. Since my first duty was to the safety of my passenger, I decided to circle the field and think of some way out of this predicament.

Below me, I saw two men on the landing strip. One held an airplane wheel high over his head and the other crossed his outstretched arms in front of him, signaling me not to land.

A few minutes later, Frank Clark took off with Al Johnson, an expert wingwalker and aerial stuntman. After one circuit of the field, Frank maneuvered alongside us. Motioning me to slow down, he pulled ahead and below. In a matter of seconds, Al had scampered out of the cockpit and made his way out along the lower right wing and onto the upper wing. Frank’s airplane was close now; he was nodding and signaling. Finally I got the message: Come in close so Al can hop aboard.

Reluctantly, I moved in toward Al, my left wing directly over the right wing of Frank’s airplane. I felt a sudden addition of weight on the left wing. Al was aboard.

He climbed through the rigging to the step at the side of my cockpit. Leaning in, he shouted over the engine noise, “Hi, Jerry. Cruise around close to the field. They’ll bring up a wheel. I’ll get it and put it on for you.” It was almost casual.

Bob Lloyd, another motion-picture pilot, took off with Ivan Unger, a wheel, and 20 feet of rope. Ivan, in his early 20s, was a professional wingwalker and parachute jumper, short in stature but long on courage. He had flown with me on many a Sunday show, hanging by his feet from the wing skid or landing gear.

At 1,500 feet and 70 mph Al made an extremely difficult job look easy. Grasping the short strut on top of the upper wing, he nimbly hoisted himself up and assumed a crouching position to await the rendezvous with Bob, Ivan, and the wheel. Soon they approached from behind, slightly above and to my left, and Ivan began lowering the rope, the wheel dangling at its end.

Al reached up an anxious hand for the oncoming wheel. I throttled back a little. The turbulence made it difficult to maintain position, and the dangling wheel bobbed in the rough air. Al reached forward to grab the wheel just as a short, upward movement of Bob’s airplane caused the rope to tighten. Ivan let go of the rope, thinking Al had the wheel. The wheel passed two feet in front of Al’s outstretched hands and plummeted to earth, trailing the rope and looking like a comet. My heart went down with the wheel.

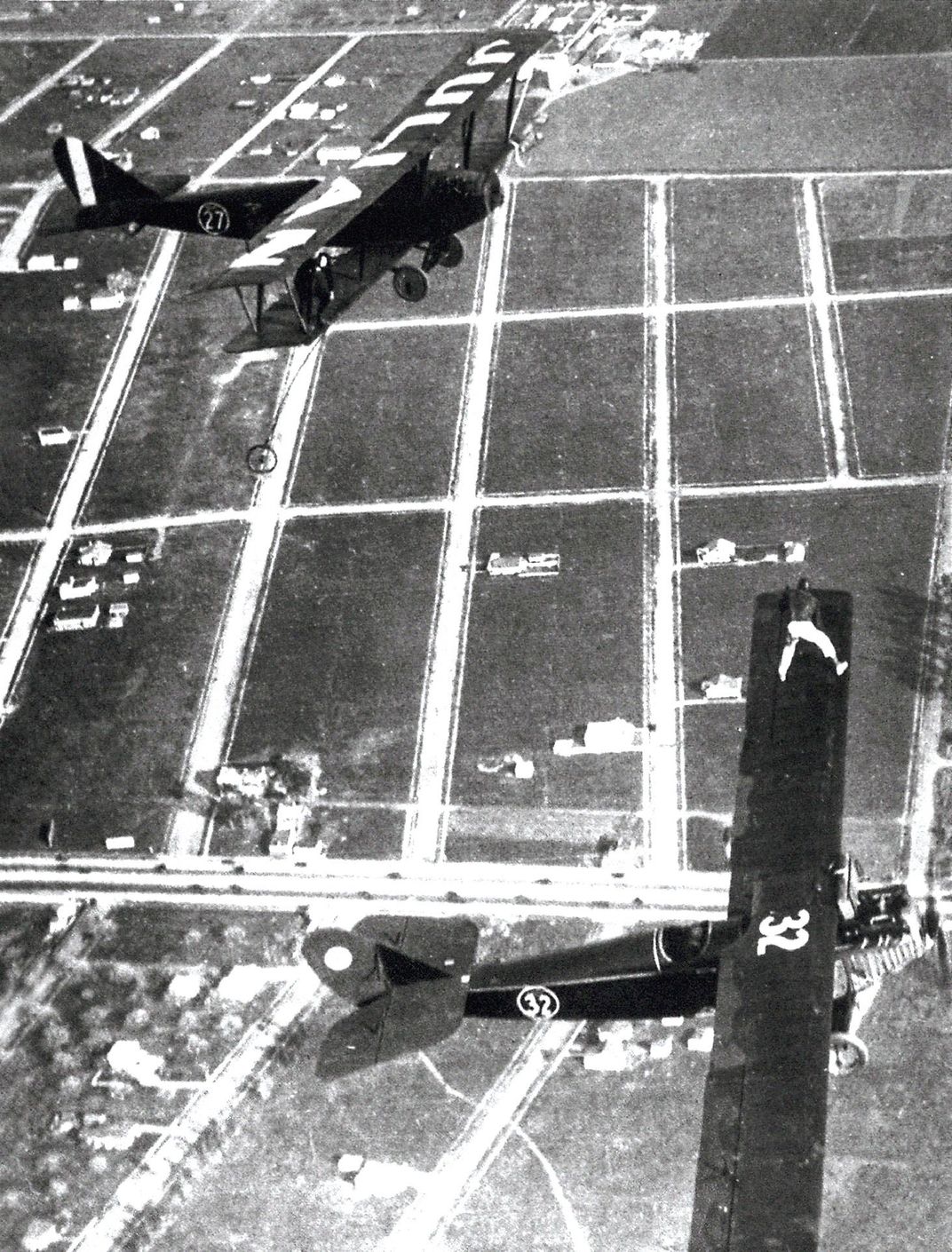

The boys on the ground had an idea. It was actually Art Goebel who solved the problem: Why not try a wheel without a tire on it? It would be lighter and offer less wind resistance. Art and Ivan were soon airborne in Art’s airplane, old Number 27, with Frank and a newsreel cameraman hot on their heels to record the event for posterity.

Soon Art’s airplane approached. I could see Ivan out on the wing with a wire-spoked wheel. Al scrambled back to his position on my upper wing. In a few minutes, I was in close formation with Art. Al reached up, fighting the 70-mph wind blast. He seemed to reach out at just the right moment—and closed his fingers around a handful of wire spokes. Smiling from ear to ear, Al slid down a strut with the wheel in one hand and made his way to the empty axle. Using both hands and feet while engaging the wheel, he worked at it for what seemed an unusually long time.

From my cockpit I could barely see what was going on, but the extended delay bothered me. I sensed trouble. Finally Al came to the cockpit with a worried look on his face. “I can’t get the wheel on far enough to put the bolt through the axle. It’s the wrong size wheel, and the hub is too damn wide,” he hollered.

Without the bolt through the axle, the wheel could slide off in a bank or on landing. While I was pondering the next move, the motor spit, coughed, and died. I glanced at the gas gauge—empty. After a few convulsions, the propeller stopped at a 45-degree angle.

Al, momentarily concerned by the dead motor, suddenly brightened. “Go on in and land her, Jerry. I’ll hold that wheel on with my foot.”

He slid back to a sitting position on the lower wing, hooked his right foot under the landing gear strut, and then pressed his left foot hard against the outer hub of the wheel. By exerting constant pressure, he could keep the wheel from sliding off the axle. He gave me the okay signal, and I started my glide downward. I had little choice. With the motor silent and the prop blast gone, we descended in eerie silence. Everything depended on keeping enough gliding speed to maintain control without losing altitude too soon before reaching the landing area.

I passed over the trees at the eastern edge of the field as I had done a hundred times before, but never, since my solo flight, was I so concerned about the outcome of a landing. Dropping the nose, I glanced to the right and left, then focused my attention straight down the landing strip. A crowd had congregated to witness the crash, and an ambulance stood by. But the runway was clear for the dead-stick landing.

The right wheel and tail skid touched down, then the bare rim, which screeched along the landing strip. The airplane tried to yaw left, but right rudder corrected it, and we rolled to a stop.

People rushed toward the airplane cheering and yelling. You’d have thought we’d just completed a nonstop Pacific crossing. Everyone was happy, especially Art Jensen, the mechanic, who was still holding the missing bolt in his hand.

Frank Clark, Art Goebel, Al Johnson, and F. Gerald (Jerry) Phillips were among the 13 Black Cats, an aerial troupe based at Burdett and Clover fields from 1924 to 1929 in the Los Angeles suburb now named Inglewood. By July 1925, the Burdett Field Air Meet attracted thousands to watch races and stunt flying. Black Cats set fixed prices by the stunt, such as $100 for a plane-to-plane transfer, a wage model adapted in 1931 by Florence Lowe “Pancho” Barnes when she founded the Associated Motion Picture Pilots to provide insurance, safety standards, and guaranteed wages for film pilots.

The late F. Gerald Phillips was a Hollywood stunt pilot. He wrote about his close call in a Curtiss Jenny in 1987.