Valentina Tereshkova’s Journal Sheds New Light on Her Historic Spaceflight

The first woman in space had code words to inform the ground of problems, from sickness (“palm tree”) to engine failure (“elm tree”).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Tereshkova-flight.jpg)

Space buffs around the world got a treat last month with the release of the flight journal that Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, took onboard her Vostok-6 spacecraft 50 years ago.

The journal’s publication missed the anniversary of Tereshkova’s June 1963 mission by a few months. But given traditional Russian secrecy, it’s remarkable that the logbook was released to the public at all. In fact, few such documents from the pioneering Vostok flights have seen the light of day in the past half century.

Tereshkova’s 100-page handwritten logbook, prepared before her flight, was her main reference to the critical tasks she would have to perform during the mission. During the flight she made many additional entries, documenting the progress of the mission through touchdown and the moments immediately after landing. The hastily scribbled notes stand out from the neat handwriting done in a classroom in Star City before the flight.

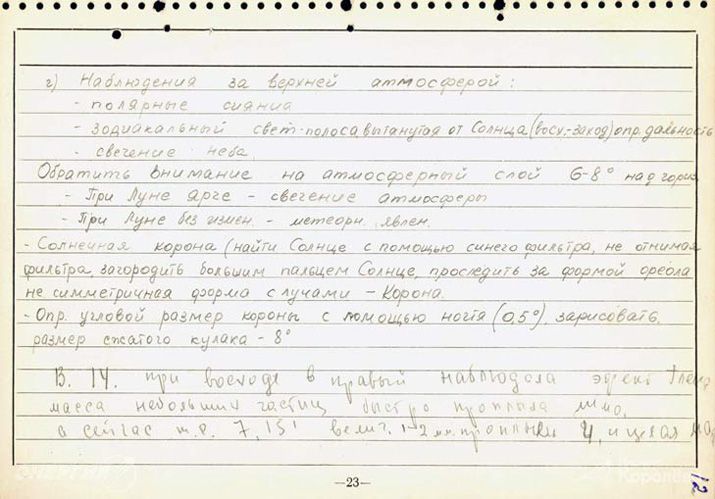

Tereshkova’s mission was the last in the Vostok series that began with Yuri Gagarin’s first spaceflight in April 1961. All of the Vostok cosmonauts were strictly prohibited from speaking openly over the radio about their status, especially about any health issues or technical problems. Instead, they used code words drawn from the world of botany. Now, thanks to Tereshkova’s journal, we have a complete list of trees, plants and berries that were to be used in these coded messages, with their associated meanings. For example, mentioning the word pal’ma (palm tree) would indicate that the cosmonaut was not feeling well. Ryabina (Rowan tree) meant that she had experienced vomiting. The misfiring of the braking engine would be telegraphed with the word “vyaz” (elm tree), while “olkha” (alder) meant that the attitude control system had malfunctioned. Tereshkova never had to use any of the coded phrases in flight, but a complete list of terms available to her (with their English translations) can be found here.

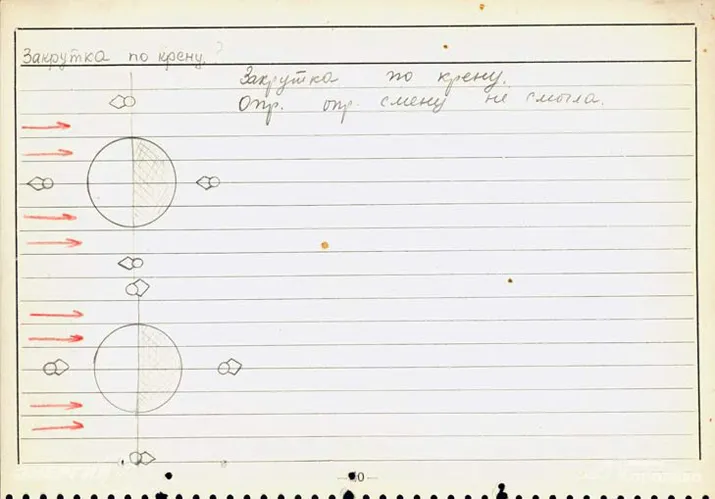

Tereshkova’s diary confirmed previous reports that she failed in her first attempt to manually orient the spacecraft while in orbit. The exercise was considered critical if the automated attitude control system malfunctioned, in which case she would have to turn the Vostok around and point the braking engine in the direction of travel to slow down and re-enter the atmosphere. In today’s world of virtual reality training and flight simulators, it’s hard to believe that Tereshkova got her first chance to practice this (potentially) life-and-death maneuver during the second orbit of the real flight!

The cosmonaut made notes in her logbook indicating that during her first attempt to maneuver the spacecraft, it kept tipping to the side. Warning lights indicating a wrong orientation along all three axes also came on, according to Tereshkova’s notes. She also noted that when she activated the manual control, she heard a sound like knocking on an empty can.

Tereshkova tried again to re-orient her spacecraft on the second day of the mission, so that she could point a camera out the windows for planned observations of Earth. Once again, her notes indicate that the ship kept drifting to the wrong orientation. Undeterred, she tried to wait for the right moment to snap her pictures.

Previous accounts of Tereshkova’s mission say that she finally succeeded with the critical manual control test on the last day of the mission. However, her flight journal, while confirming that she did hold the spacecraft in position for a braking maneuver for 25 minutes during the 45th orbit, concludes with her note that the Vostok constantly drifted away along the bank axis.

When watching the sunrise during the 14th orbit, she observed the “Glenn effect,” referring to numerous shiny ice particles from the spacecraft, first described by John Glenn during his orbital mission a year and a half earlier. It’s the only reference in the document to the U.S. space program.

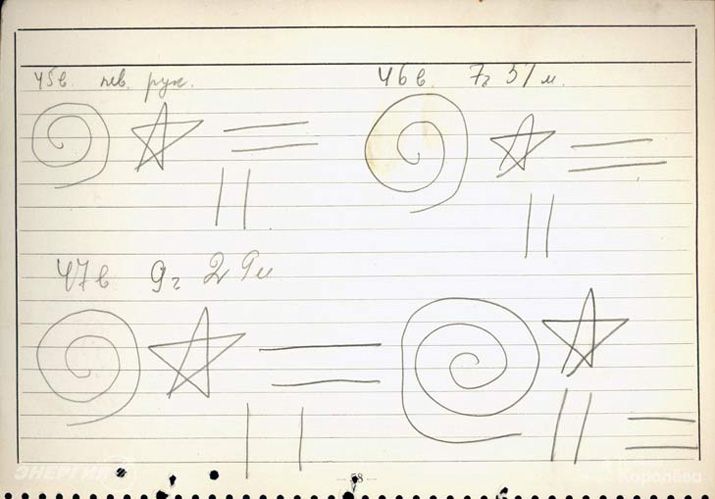

The pioneering nature of Tereshkova’s mission is illustrated most vividly in her drawings depicting stars and spirals, which she was required to do several times a day during the flight, apparently in an effort to assess the effects of space travel on her cognitive abilities. To an untrained eye, her doodles look the same throughout the journal, and they remind us how strange and unknown the space frontier still was when Tereshkova made her only trip to orbit half a century ago.

Scans of Tereshkova’s flight journal with official commentary in English can be viewed at this Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation website.

Anatoly Zak is the editor of RussianSpaceWeb.com and the author of Russia in Space: The Past Explained, The Future Explored published by Apogee Prime this year.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnatolyZak.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnatolyZak.jpg)