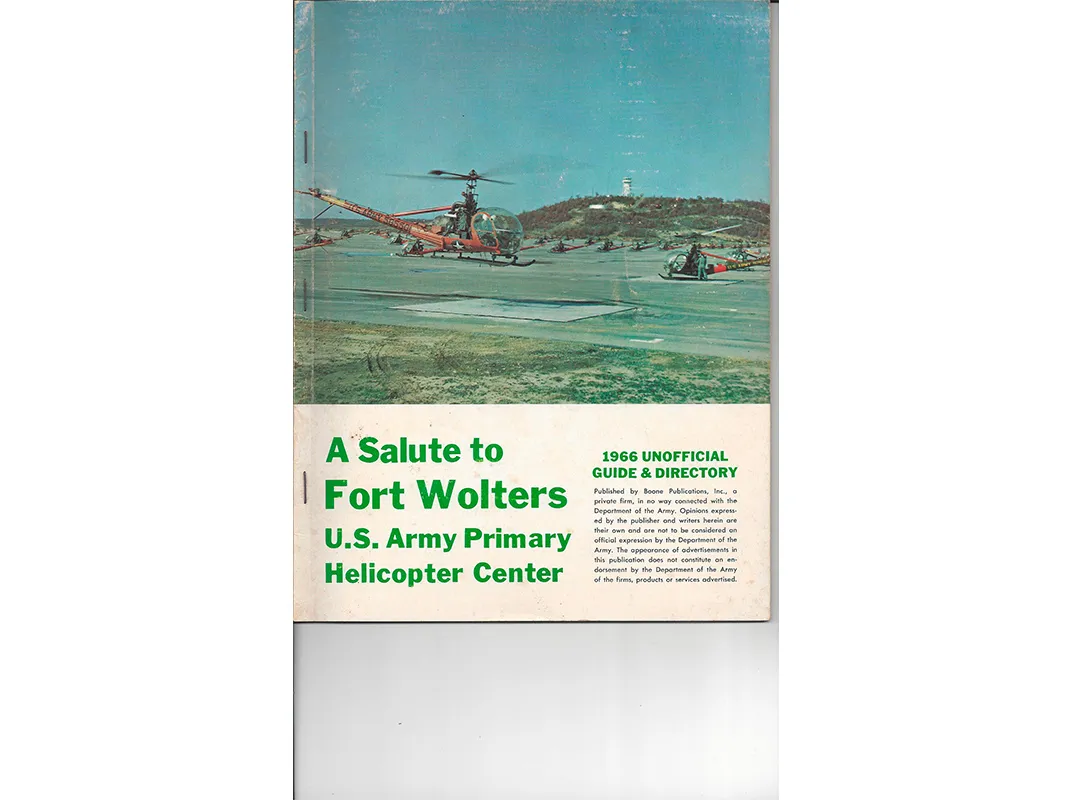

Where Huey Pilots Trained and Heroes Were Made

Basic training for a dangerous job.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/35/2f35e16e-d6fd-4a22-adf9-5db7256c17ef/hueys_ft_wolters.jpg)

Gerald Hickey spent 17 years as a civilian in Vietnam, both before and during the U.S.-led war. While working as an ethnographer for the RAND Corporation, Hickey often rode in Army Huey helicopters, accompanying Green Berets on visits to remote villages.

“I hated choppers,” Hickey recalled in 2006, “the way they banked in the turns, flew toward treetops, and jumped up at the last minute. I had to sit in the seat and cover my eyes with my hands.”

But he appreciated the Army fliers more during a visit to the remote Green Beret camp Nam Dong in 1964. On July 5, hundreds of enemy soldiers attacked after midnight. The defenders held the perimeter through the night, but in the morning, enemy machine guns drove off six Marine Choctaw helicopters attempting to deliver reinforcements. Hickey recalled a wave of fear and disappointment among the survivors. But then a single Huey swooped over the treetops, door guns blazing. The Army crew cleared a path for the relief helicopters to return. “Fearless, those kids,” Hickey said.

“We were all young and crazy then,” says Jim Messinger, who flew Hueys in Vietnam. “My first job as an adult was to fly around in a helicopter and let people shoot at me. I was 20 years old in flight school.” That school was the Primary Helicopter Center at Fort Wolters, Texas. Of all the helicopter pilots who flew in Vietnam, 95 percent passed through the center at Wolters. Located in north-central Texas, the school, which ran from 1956 until the end of the Vietnam War in 1973, was an essential part of the pressure cooker process that transformed anybody who qualified—from teenagers to grizzled combat officers—into world-class helicopter pilots.

“There was a huge range of experience,” recalls A. Wayne Brown, who worked at Wolters as a flight instructor for contractor Southern Airways. “Some had never been in a plane, and some were fixed-wing pilots. I had to show some of them how to buckle a seat belt—they were that green.”

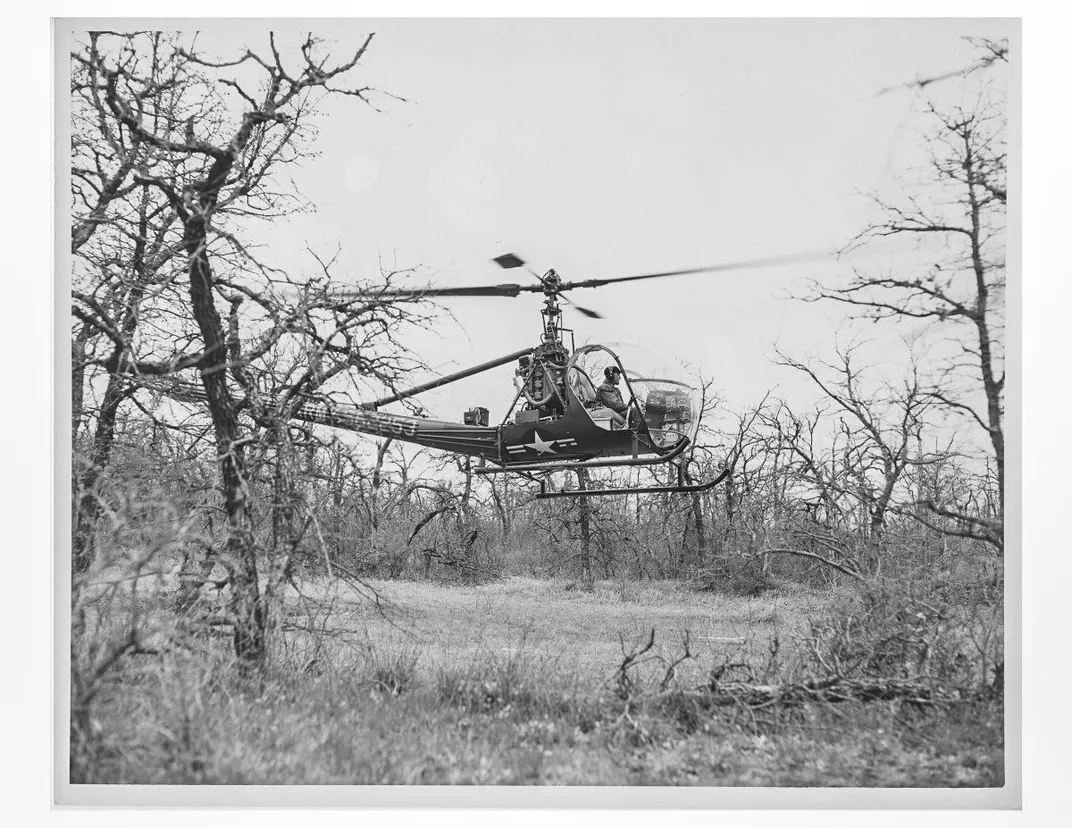

Wolters relied on three models of small training helicopters, all powered by gasoline-fueled piston engines. These were cheaper to operate than the Hueys and in many respects were trickier to fly—hence good trainers. None of them came with instruments for flying in clouds—such advanced training happened elsewhere, such as Fort Rucker, Alabama. Wolters was all about learning to control flighty machines under “contact,” or visual, conditions. Students—mostly warrant officer candidates, but commissioned officers too—flew day and night. Flight school had two phases of instruction, each eight weeks long: Primary I and Primary II.

“Primary I taught ’em how to fly a helicopter. Primary II, how to use it,” says Brown. “Our workday was about 6 a.m. to noon, or noon to 6 p.m. It was probably the best flying job I’ve ever had.” Given Brown’s long flying career, that’s saying a lot: After the war he flew offshore helicopters, taught military pilots in Iran, then operated a variety of helicopters in the South, before becoming assistant chief instructor at Bell Helicopter’s training academy in Texas. When actor Harrison Ford bought a Bell 407 and needed a world-class instructor, Brown got the assignment.

Southern Airways pilots like Brown taught basic skills in Primary I, and military pilots just back from the war typically handled Primary II. During my visit to Wolters, Brown introduced me to Dwayne “Willy” Williams, a combat veteran who added wartime lessons to the Wolters curriculum. Williams came to Wolters as a Warrant Officer Candidate, then flew UH-1B gunships in Vietnam. After the war Williams stayed in the rotary-wing world, including working as chief test pilot for manufacturers like Bell and MD Helicopters. He was copilot on the first test flight of the Bell/Agusta BA609, the first civilian tiltrotor.

Instructors took three students at a time and got to know them well. Now, 50 years on, veterans of the program still remember class numbers and hat colors, flying buddies and instructors. “Every eight weeks we threw out the old bunch and took on a new one,” Jim Messinger said as we had lunch in Woody’s, a Quonset-hut diner on the main drag of the nearby town, Mineral Wells. “College courses should be like that, eight weeks long.”

After flying Hueys in Vietnam, Messinger returned to the fort for two years, serving as an instructor and standardization pilot. He spent a second year in Vietnam as a Sikorsky CH-54 heavy-lift cargo pilot.

Now Messinger teaches computer science at nearby Weatherford College. He devotes his spare time to setting up the National Vietnam War Museum, to be located in Mineral Wells, just over the hill from one of the wartime heliports. After filling his garage with memorabilia donated for the future building, he found space in a hangar. When we visited the metal building, he showed me a box with dozens of framed class photos circa 1967: rank upon rank of smiling students hoping to fly in combat. I asked about faces marked out with red grease pencil: Some washed out of the program, Messinger said, and others died in action. “I stopped keeping track of all the students after a while. It was just too hard.”

Messinger recounted his days teaching the basics of hovering and flying a piston-engine helicopter at no-frills facilities called stagefields, spaced well away from the main heliports. Practice at the stagefields helped build the complex skills needed for landings and takeoffs. Instructors threw inflight emergencies at the students without mercy.

“It was intense,” said Brown. “No loose time, no boring holes in the sky.”

Wolters trained pilots for all branches of the armed services and for allied countries, in particular the South Vietnamese army—a total of 41,000 in 17 years of operation. At the peak of activity, just before U.S. forces began a long withdrawal from the war in 1969, Wolters was sending 575 pilots per month for advanced training at Fort Rucker. There they learned instrument flight rules, tactics, formation flying, and how to operate the bigger, turbine-powered Huey. The entire process—from boot camp to Wolters through graduation from Rucker—took less than a year. In that time, a high school graduate was transformed into a UH-1 pilot, holding the rank of warrant officer.

A teenage enlistee at the recruitment center might have had visions of an exciting, all-expenses-paid helicopter career, but he may have missed the part about having to go through not just one but two spit-and-polish phases called boot camp. The second, at Wolters, was called preflight school, and for warrant officer candidates it lasted four miserable weeks, a purgatory ruled by a living terror known as the TAC (Training, Advising, and Counseling) officer, who specialized in finding all levels of imperfections, down to misalignment of socks in the drawer, uniforms in the closet, and notebooks on the desk. An infraction by one WOC could bring down fire upon his entire preflight class.

“It was like OCS [Officer Candidate School], all spit-shine,” said Messinger. “The more you cleaned, the more they looked. If the sink was too clean, they took it apart to find something wrong. They got us up at midnight and turned us into the hallway. But after four weeks it got easier.”

Why the grief? Top-notch flying skills wouldn’t be enough to cope with the chaos and fury of combat. An aircraft commander in Vietnam—even if too young to vote—was going to hold life-and-death power over his copilot, crew, passengers, and many others within range, so he needed a cool and steady temperament. Occasionally a senior pilot was injured, and brand-new copilots had to take command. And they could face such trials very soon after landing in Vietnam. Williams recalled that one of his classmates, having been called into action while on an orientation flight with a veteran aircraft commander just four days into his first tour in Vietnam, was killed in action. Jim Martinson, another student, had been in-country just a month when he was shot down twice in one day. “I can remember the first combat assault I saw like it was yesterday,” Williams said. “It was intense. We were on the second lift, and every time a slick [on the first lift] would get on the radio you could hear the gunfire. There were gunships flying over the targets, [white phosphorous] smoke, and the enemy firing from the treelines. I thought, I don’t know how long I have to live. It was surreal, like: How did I end up in this movie?” Hence the daily harassment of warrant-officer candidates at Wolters. “The first four weeks was like a filter,” Messinger said. “If you can’t take this, you can’t take combat either.” Messinger recalled the rebellion of an experienced non-com with a fine service record. “He said, ‘I’m a staff sergeant and I don’t have to put up with this.’ So he just left and went back to his E-6 rating.”

A few flight instructors carried the tradition of torment past the preflight barracks and into the air, screaming at their students and rapping them on the helmets with a stick. But that was not standard procedure, and as critical tests approached, students who struggled to learn under one instructor’s style could request an alternate.

as we approached a row of two-story dormitory-style buildings, Messinger stopped his Dodge van and pointed to a second floor window at the end of Building 779: his Spartan quarters while a Warrant Officer Candidate.

By comparison, commissioned officers who came to Wolters for identical flight training enjoyed the good life. They avoided the first month of hell and received a stipend to live off-base, so they usually had enough cash for amenities and weekend misadventures.

“The pay was good,” recalls Hugh Mills, who was a lieutenant when he arrived at Wolters in 1968. To stretch his salary he shared an apartment in Weatherford, a half-hour east, with other officers. They commuted in style. “One officer I knew had a Dodge Charger, one a Corvette. Mustangs were popular,” Mills says. “Mine was a 1968 GT350 Mustang, four-speed, two plus two, with a Pony package.”

Whether a privileged officer or lowly WOC, all students faced the risk of failure. There were constant tests and emergency drills. The most hair-raising of the flight maneuvers required trainees to cope with complete engine failure: They had to take their hurtling, unpowered machines all the way to a screeching stop on the ground. It’s called a touchdown autorotation. After the instructor pulled off the power and left the main rotor to windmill, students had only seconds to adjust the controls and find a safe landing spot—which could be out of sight behind them. This taught them to scan instruments constantly, and be aware of traffic, terrain, and wind direction at all times. Over his career of flying and instructing, Brown practiced the maneuver more than 80,000 times.

Mistakes during autorotation practice at Wolters caused aircraft damage, injuries, and a handful of fatal crashes. “But after 200 flight hours,” Messinger says of the whole trial by fire, from Fort Wolters through Fort Rucker, “we were super-highly trained by civilian standards.” Williams recalls that his training at Rucker ended with a few days at a forward helicopter base that simulated conditions students would find in Vietnam, during which students were awakened at night with big firecrackers and alert horns that ordered them to their ships at a flat run.

If the students failed a key test along the way, they washed out of helicopter school. During the peak enrollment years, 1968 and 1969, about 15 percent failed to graduate from Wolters. While noncoms and officers could go back to work they had been doing, a newly arrived Warrant Officer Candidate who failed had no such fallback, and likely would end up slogging through rice paddies in Vietnam.

For those who graduated as warrant officer pilots and went to Vietnam, “you were automatically looked upon as a leper by the grizzled old combat veterans—anywhere from 19 to 21 years old,” Williams recalls of his days as a new pilot. “[But the training] worked because the majority of helicopter pilots made it home, and it’s hard to put a figure on how many thousands of lives were saved as a result of the Huey, and the brave young men who flew them.”

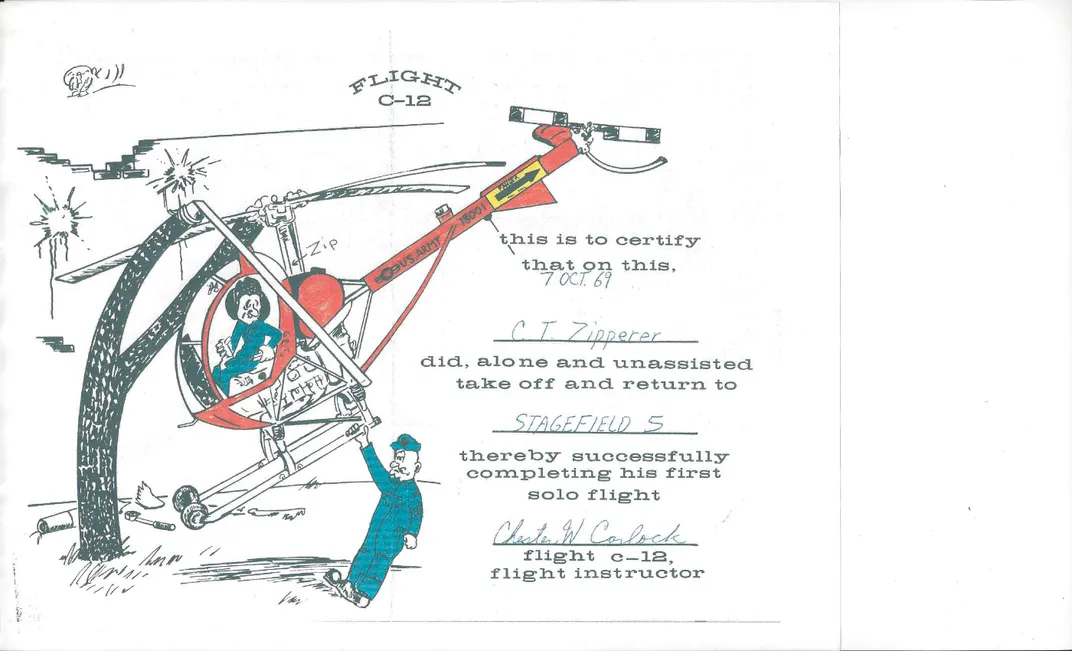

Of all the Stateside tests to earn that ticket, the most critical and memorable was the solo flight and the check ride leading up to it. Some students never developed the hand-eye coordination to keep the aggravating machines steady in a low hover, and so never got a chance to fly solo around the field three times and move on. The strict timetable at Wolters required students to qualify for soloing after 10 to 15 hours of dual instruction.

Students who survived the solo saw immediate and happy changes. One happened on the bus ride at the end of the day: The vehicle pulled over at a Holiday Inn, and fellow students dragged the new soloist out and threw him into the swimming pool, regardless of weather. He also got a wings emblem to sew on his cap. Soloing brought great improvements to the social life of the warrant officer candidate who, unlike officers in the same training, had been confined to base and subject to TAC officers’ harassment. Students with the big “W” emblem on their caps could finally get leaves, and many sought companionship in female-rich places such as the American Airlines stewardess school in Dallas, or Texas Women’s College in Denton.

Fear of failure also eased (slightly). With each successive week, the Army became more invested in fledgling pilots, so flunking a test was more likely to lead to remedial instruction than to being tossed out.

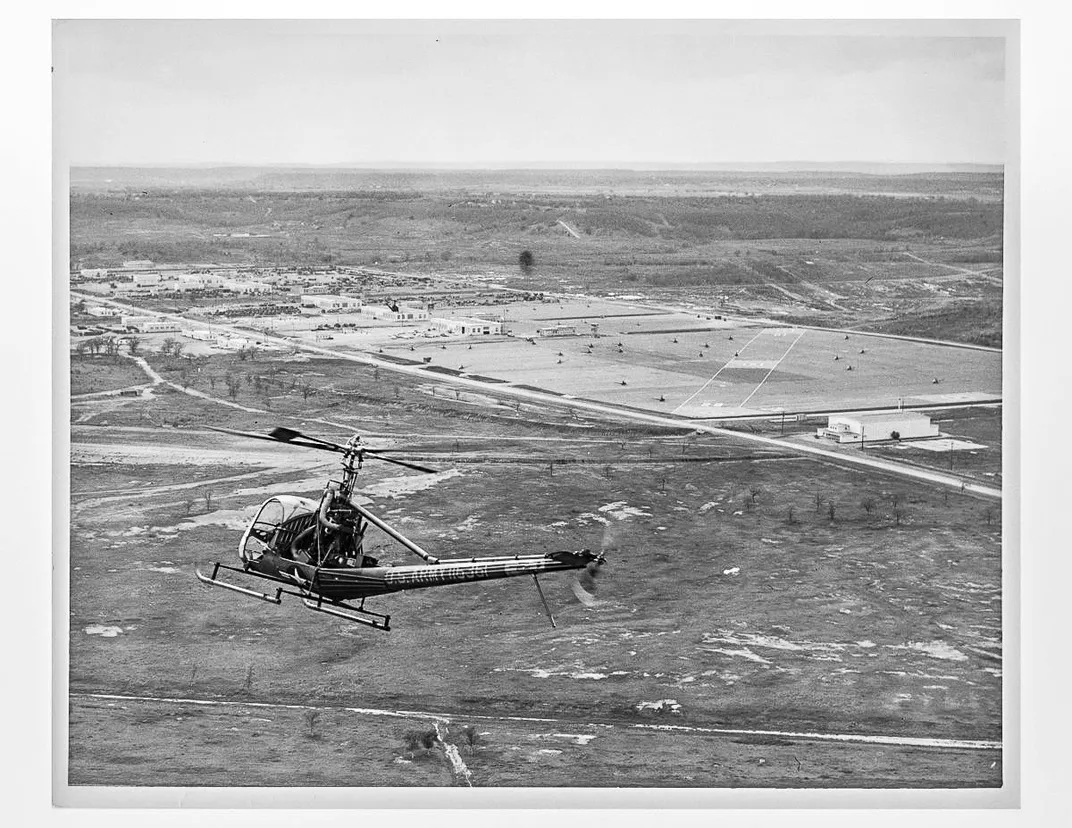

wolters began with a single heliport and four stagefields for daily practice. In 1965, with Vietnam demanding more helicopter pilots, the fort added two big heliports and 21 stagefields.

The Army gets credit for starting the pilot pipeline as early as it did: When the program started, no war was under way, nobody had worked out the cavalry-like tactics, and the gasoline-powered helicopters then in use were barely adequate even for war games. The year Wolters opened, Bell’s UH-1 had just entered flight testing as a prototype, and was still four years from the assembly lines.

Students in the small, piston-engine helicopters learned to cope with marginal performance: In summertime, the OH-13 models could barely get off the ground. “With two students on board on a hot day, using the skids for a running takeoff was the only way to get in the air,” says Brown.

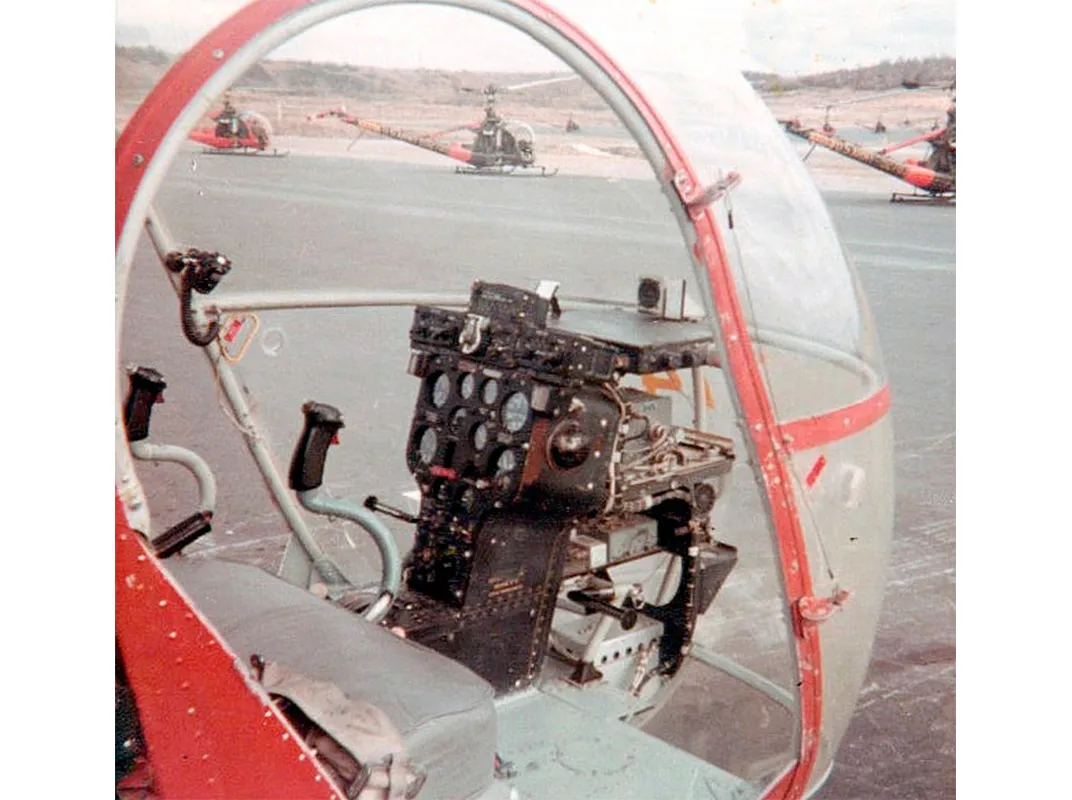

Bumping and scraping the skids along the pavement was a skill all students at Wolters learned, no matter which model they flew. For one, it was a simple but effective safety precaution at the crowded heliport. Because so many helicopters were parked on the apron, and because beginners find precise hovering so difficult, the school feared collisions during taxiing, so instructors had their novices skid down the traffic lanes on the way to takeoff, applying just enough power to be light on the landing gear but not so much as to rise off the ground.

That noisy practice would come in handy later: “Many times in Vietnam,” Williams says, “flying a loaded gunship on a hot day, you’d have to skid down the runway until you achieved translational lift.”

Wolters’ original, or Main, heliport is barely visible now, because of changes that followed after the Army handed most of the fort over to Mineral Wells for business redevelopment. Most of the concrete expanse, once home to 550 helicopters, is covered by rusty fences and heaps of even rustier oilfield equipment. Thanks to a cadre of veterans and volunteers, though, a restored main entry looks as good as ever: Visitors to what is now an industrial park drive under a helicopter-theme archway. On the left side of the orange, steel-frame archway sits a restored Hiller OH-23-D. A sturdy and powerful 1950s helicopter, it’s still used for light cargo and cropdusting around the world. On the other side of the arch sits the TH-55A Osage, a light two-seater originally developed in the 1950s by the Hughes Tool Company’s Aircraft Division for sale to police departments. A similar version is still sold today by the Schweizer division of Sikorsky Aircraft.

The third helicopter type used at Wolters was the H-13, the military version of the bubble-canopy Bell 47 civilian models made famous by old movies and television shows. At the peak, the fort had swept up nearly 1,300 helicopters for its trainees. A tornado in April 1967 damaged 179 of them.

By the end of 1968, the three heliports were handling at least 2,000 takeoffs and landings daily, five days a week. “It was like Oshkosh every day, twice a day,” said Williams as we toured the outskirts of Mineral Wells in Wayne Brown’s SUV. “The most exciting part of the day was the recovery, when there were 600 or 700 helicopters all coming in about 11 a.m. We did have a couple of midair collisions—I’m not sure I’d do it that way now.”

We set out with hopes of getting into the now-abandoned Dempsey Heliport on U.S. Highway 180; I’d heard that it had a well-preserved aerial map in one of its briefing rooms, showing the training areas in great detail.

Seeing Dempsey Heliport’s red-and-white water tower, Brown turned down an access road and stopped at the gate. There was no sign of activity. The only suggestion of something valuable was a padlock on the gate and a sign reading Junco Inc.

As we stood at the gate, Williams said, “Darn! We need a helicopter to get in there.”

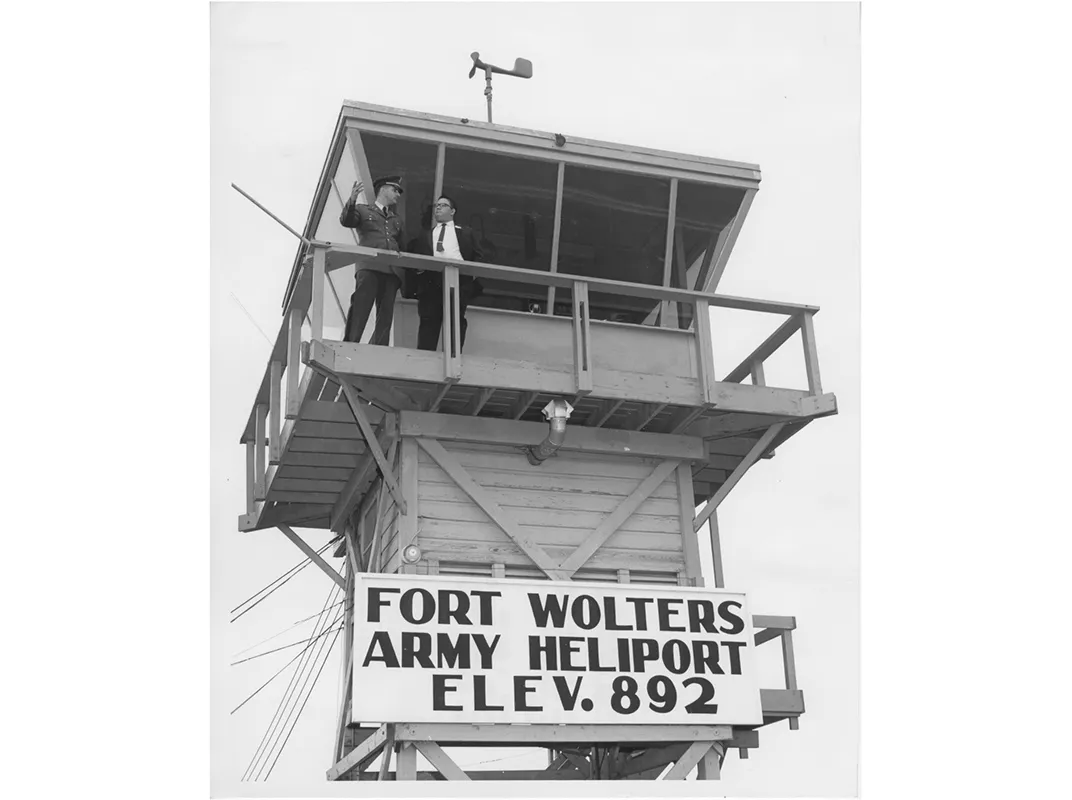

Fortunately, no helicopter was necessary to get a good look at remnants of the stagefield known as Bien Hoa, two miles north. Like all the stagefields, it had a small control tower, paved strips and pads for landing practice, and a building for students to study in between flights.

Seeing the rusty steel frame of an air traffic control tower from the county road, Brown and I climbed a gate and then the rusty stairs to get a bird’s-eye view. Brown pointed to remnants of an asphalt strip nearby, where helicopters pulled up for refueling. Other long strips and pads to the east were for practicing approaches and autorotations.

The close attention to off-airport skills at Wolters, and later at Rucker, makes sense in light of what the new armada of gas-turbine helicopters offered to U.S. forces in Vietnam: the ability to land, or at least hover over, any place in the war zone. This agility compensated for helicopters’ drawbacks relative to fixed-wing aircraft: slowness, expense, vulnerability to small arms, and shrimpy payload. By 1965, swarms of Hueys proved able to shift hundreds of troops in cavalry fashion, accompanied by gunships firing on enemy forces who’d be untouchable by any other weapons platform. They retrieved wounded soldiers and restocked ammunition. Larger helicopters hauled artillery tubes and bulldozers.

But fully exploiting these virtues required extraordinary flying skills. Often success depended on the ability to hug the terrain in nap-of-earth fashion, then plunge into tiny clearings among the trees. Some of those clearings were barely bigger than the helicopter itself. And taking off was even chancier. Given high air temperatures and heavy payloads—such as a load of rescued troopers—pilots had to know how to use every foot of the space available, and every pound of lift.

While taking off may sound easy—Don’t helicopters just rise straight up?—a helicopter climbing vertically can’t develop nearly as much lift as a helicopter that climbs out diagonally, with forward airspeed. In the confined areas around Wolters, which were marked by tires of different colors to note their difficulty, students learned how to get out of very tight spots. It was a lesson they’d use often.