The Science of a Tourist Trap: What’s This Desert Doing in Maine?

Maine’s “most famous natural phenomenon” is also a reminder about responsible land use

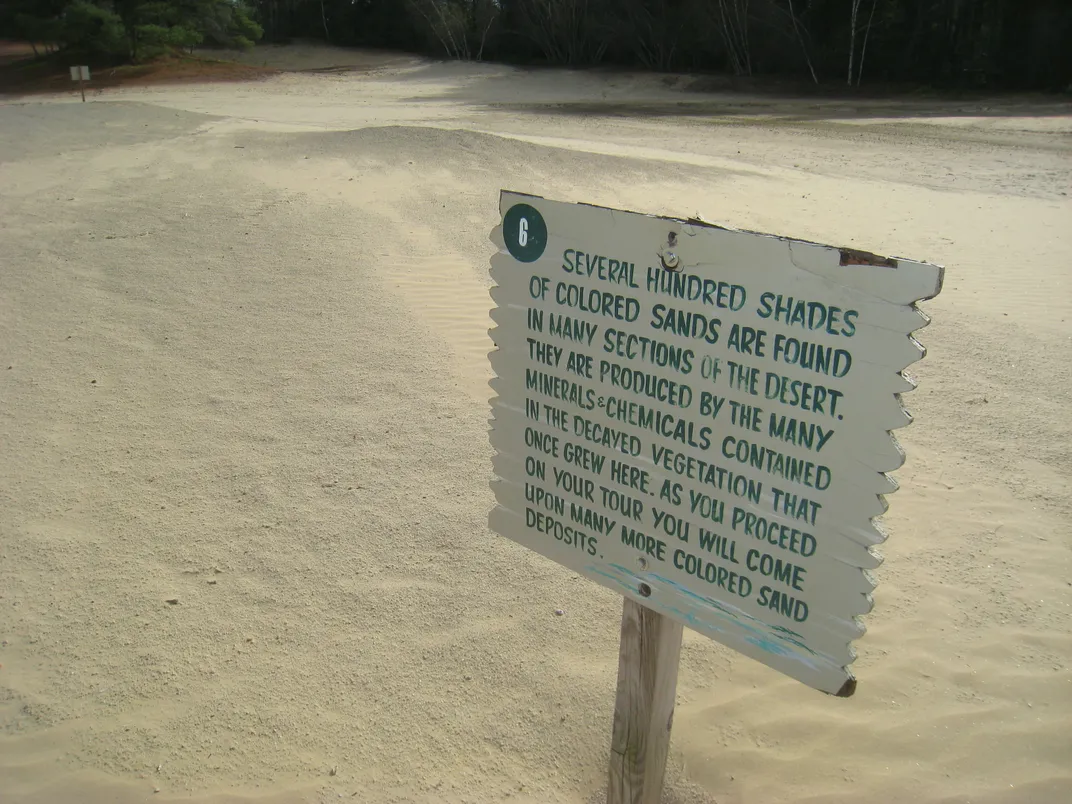

Maine evokes images of lush pine forests and quintessential New England lighthouses, but tucked away next to the coastal town of Freeport, Maine, lies an unexpected site: over 40-acres of sand and silt, dubbed the Desert of Maine. The rolling sand dunes aren't a true desert–the area gets too much precipitation to fall under that category—but it's not a kitschy attraction created from trucked-in sand. The desert, which does attract around 30,000 tourists each year, is a story of ancient geology meets modern-day land misuse.

Ten thousand years ago, during the last ice age, large glaciers covered what is now Maine. These glaciers scraped rocks and soil as they expanded, grinding rocks into pebbles, and grinding those pebbles down into what is known as glacial silt—a granular material with a texture somewhere between sand and clay. Layers of glacial silt piled up as high as 80 feet in some parts of southern Maine. Over time, topsoil began to cover the silt, hiding the sandy substance beneath a layer of organic matter that encouraged the growth of Maine's iconic coniferous forests.

Native American tribes, including the Abenaki, took advantage of the fertile topsoil, farming the land long before European settlers claimed it as their own. But the late 1700s saw an expansion of Maine's agricultural business, as settlers and colonists moved northward from Massachusetts (or sailed from Europe) in search of land. One such farmer was William Tuttle, who bought a 300-acre plot of land next to Freeport in 1797. On that land, Tuttle founded a successful agricultural enterprise, growing crops and raising cattle in the shadow of a small post-and-beam barn he built. His descendants diversified the business, adding sheep in order to sell their wool at textile mills.

But there was trouble on the horizon for the farm. The Tuttle family wasn't properly rotating their crops, depleting the soil of its nutrients. The Tuttle's sheep enterprise also wreaked havoc on the soil as the livestock pulled vegetation out at the roots, causing soil erosion. One day, the family noticed a patch of silt the size of a dinner plate—their poor land management had caused the topsoil to completely erode, revealing the glacial mixture below their land. The Tuttles didn't immediately give up on the farm, but eventually that patch of sand grew to cover over 40 acres, swallowing farming equipment—and even entire buildings—in the process. By the early 20th century, the Tuttles had completely abandoned the land.

In 1919, a man named Henry Goldrup bought the property for $300 and opened it as a public tourist attraction six years later. Today, most visitors chose to explore the grounds via a 30-minute tram tour, which takes visitors around the perimeter of the desert and explains the history and geology of the desert.

While the Desert of Maine is certainly an intriguing tourist attraction, it's also a reminder of what can happen to farmland that isn't properly cared for. The same overgrazing and poor rotation of crops (along with years of sustained drought) contributed to the Dust Bowl, a decade of severe dust storms that devastated the south Plains in the 1930s. But it's not just a risk of years past—currently, the United States Department of Agriculture's Natural Resources Conservation Service has labeled areas in California and across the Midwest—foci of huge agricultural activity—as being at high or very high vulnerability for desertification.

Desert of Maine: 95 Desert Rd. Freeport, Me. 04032. (207) 865-6962.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/bc/febcf2ac-9527-4b93-b316-14e9f1d9587a/4869571615_fd490d9f2f_o.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)