Who Says Horses and Cows Can’t Be Artists?

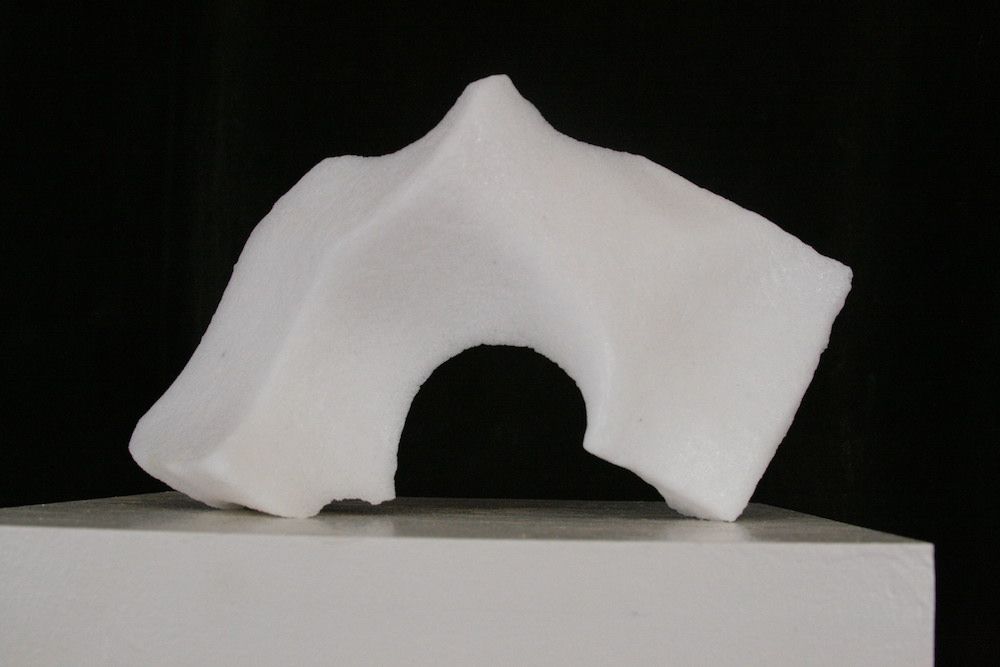

The sculptures on display at the Great Salt Lick Contest in Oregon are the work of cattle, horses, sheep and deer

What exactly makes something qualify as a piece of art? For Whit Deschner, nothing is out of the question, especially if it’s a well-licked salt block.

For the past 13 years, the retired fisherman turned writer and photographer has been organizing The Great Salt Lick Contest, where he invites fellow ranchers, farmers and anyone else with access to grazing mammals to submit carved salt licks. But there’s a catch: an animal must be the one responsible for the sculpture and can use nothing but its tongue to shape divots, swirls and whorls into the 50-pound square block.

What started out as a joke amongst friends has morphed into a friendly competition that also happens to be for a good cause. Over the years, Deschner has auctioned off hundreds of salt licks and raised more than $150,000 for Parkinson’s disease research at the Oregon Health and Sciences University. (Deschner was diagnosed with the disease in 2000.)

So why did Deschner choose a salt lick, of all things, as an artistic medium in the first place?

“I was at my friend’s cabin and he had a salt lick out back for the deer,” Deschner says. “The deer had sculpted the block with their tongues and I made a comment about how it looked a lot like the modern art you see in major cities. I wanted to figure out how I could make a contest out of the idea, just for a laugh.”

That was back in 2006. To spread the word, he went door to door to local businesses to get people hyped about the competition and the chance to win hundreds of dollars in prize money. That year nearly 30 locals—mainly ranchers—submitted salt blocks to his home in Baker City, Oregon, a former Gold Rush community in the northeastern part of the state. These days he receives dozens of submissions each year from around the world. The event has proven so popular that he has divided the contest into separate categories, such as the “most artistically licked block” and “forgeries.” (The latter began as a joke for humans who decided to cheat by carving the salt lick themselves.)

“The first year I made an announcement that people can’t lick the blocks themselves, or else I’ll take DNA samples and I won’t let them participate again,” Deschner says with a laugh. “I’m actually not too concerned about it.”

Deschner has found that most participants are honest about what they submit, and that he even has a good eye for deciphering which species was responsible for carving each block.

“Deer and sheep, they’re very much realists as far as sculptors go, while cows are more impressionists, and horses have no sense of art whatsoever,” he says. “It’s the size of the tongue [that let’s me know]. Cows have a really broad brush to work with.”

Dan Warnock, a local rancher who raises beef cattle, has been submitting pieces since the contest's inception as a way to support a good cause.

"The first piece my cattle made I still have displayed in my office," he says. "It has several holes in it and is a really interesting conversation piece."

These days the contest has helped put Baker City on the map. In 2014, the town installed a four-foot-tall bronze sculpture of a carved salt lick on Main Street in recognition of the annual event. And completed salt licks have popped up at galleries and museums throughout North America, including at the Guggenheim Gallery at Chapman University in Orange, California, and the Western Front Society art gallery in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Each year, Deschner has some of his favorites cast in bronze, although that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the winners. He relies on a group of judges to make that call.

“One year I recruited candidates running for local judge, and another year it was all city council members,” he says. “I’ve also gotten local ministers involved to judge.”

On September 21, Deschner will hold the contest’s 13th auction at Churchill School in Baker City. The event will begin with a viewing, then auctioneer Mib Daily will kick off the auction. Blocks fetch about $200 a pop on average, but it's not uncommon for some pieces to go for $1,000 and up.

“The whole town comes together for this event,” he says. “It brings everyone together, whether they’re cowboys or artists.”

The deadline to submit a salt lick is September 14, and the auction takes place the evening of September 21. Download the entry form for submission here.