Why Mount Fuji Endures As a Powerful Force in Japan

Not even crowds and the threat of an eruption can dampen the eternally mysterious volcano

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/03/6203ee3b-645b-4a8b-9908-ccadc7ef64de/may2017_i02_mtfuji.jpg)

It’s dawn on the first day of January and a crowd in the hundreds has gathered at the base of Mount Fuji to watch the rising light of hatsuhinode—the maiden sunrise—usher in the new year. The Ainu, mainland Japan’s ancient indigenous people, believed that the sun was among hundreds of gods, and one of the most important. To witness a hatsuhinode is considered a sacred act.

Against a brilliant blue sky, the sun crests near the peak of the country’s tallest volcano and shimmers like a gem. When it aligns perfectly with the summit, the rare sight is called Diamond Fuji. On a hillside redoubt in nearby Fujinomiya-shi, a tour guide named Keisuke Tanaka marvels as the snowy peak, sharp against the horizon, grows indigo, then plum before retreating behind a curtain of cloud. “On clear days you can see Fuji-san from Tokyo, 60 miles northeast,” he says.

On dim days—which is to say most days—it’s less a mountain than an allegation, obscured by fog and industrial haze even 60 feet away from the summit. Many cultures hold mountains to be sacred—the ancient Greeks had Olympus; the Aztecs, Popocatépetl; the Lakota, Inyan Kara—but nothing equals the timeless Japanese reverence for this notoriously elusive volcano. Parting earth and sky with remarkable symmetry, Fuji is venerated as a stairway to heaven, a holy ground for pilgrimage, a site for receiving revelations, a dwelling place for deities and ancestors, and a portal to an ascetic otherworld.

Religious groups have sprouted in Fuji’s foothills like shiitake mushrooms, turning the area into a kind of Japanese Jerusalem. Among the more than 2,000 sects and denominations are those of Shinto, Buddhism, Confucianism and the mountain-worshiping Fuji-ko. Shinto, an ethnic faith of the Japanese, is grounded in an animist belief that kami (wraiths) reside in natural phenomena—mountains, trees, rivers, wind, thunder, animals—and that the spirits of ancestors live on in places they once inhabited.

Kami wield power over various aspects of life and can be mollified or offended by the practice or omission of certain ritual acts. “The notion of sacrality, or kami, in the Japanese tradition recognizes the ambiguous power of Mount Fuji to both destroy and to create,” says H. Byron Earhart, a prominent American scholar of Japanese religion and author of Mount Fuji: Icon of Japan. “Its power can demolish the surrounding landscape and kill nearby residents. But its life-giving water provides the source of fertility and rice.”

One meaning of the word Fuji is “peerless one.” Another interpretation, “deathless,” echoes Taoist belief that the volcano harbors the secret of immortality. Another source for this etymology, the tenth-century “Tale of the Bamboo Cutter,” offers up feudal lore (foundling in rushes, changeling child, suitors and impossible tasks, mighty ruler overpowered by gods) in which Princess Kaguya leaves behind a poem and an elixir of everlasting life for the emperor on her way home to the moon. The heartbroken emperor orders the poem and potion to be burned at the summit of the mountain, closest to the firmament. Ever after, the story concludes, smoke rose from the peak, given the name fu-shi (“not death”).

Throughout Japan’s history, the image of Fuji was used to bring together and mobilize the populace. During World War II, Japanese propaganda employed the mountain’s august outline to promote nationalism; the United States exploited the image of Fuji to encourage surrender—leaflets imprinted with the silhouette were dropped on Japanese soldiers stationed overseas to induce nostalgia and homesickness.

“It is powerful for any culture to have a central, unifying symbol and when it is one that is equal parts formidable and gorgeous, it is hard not to go all yin and yang about it,” says Cathy N. Davidson, an English professor at the City University of New York whose 1993 Japanese travelogue 36 Views of Fuji: On Finding Myself in Japan revolved around the volcano. “I do not know a single person who just climbs Mount Fuji. One experiences a climb inside and out, even amid tens of thousands of other climbers. The weight of the mountain’s art, philosophy and history climb the path alongside you.” In an almost literal way, she maintains, “Fuji is the soul of Japan.”

Artists have long striven to capture Fuji’s spiritual dimension. In an eighth-century anthology, Man’yoshu (Collection of a Myriad Leaves), a poem describes the volcano as a “living god” where fire and snow are locked in eternal combat. The 17th-century poet Matsuo Basho, a Zen master of non-attachment, meandered along its steeply winding paths with one foot in this world and the other in the next. One of his best-known haikus contrasts our temporal attempts to harness the wind with the celestial power of the mountain:

The wind from Mount FujiI put it on the fanHere, the souvenir from Edo.

Perhaps no artist used this dynamic to greater effect than Katsushika Hokusai, whose woodblock series, the original Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, juxtaposed the mountain’s calm permanence with the turbulence of nature and flux of daily life. The long cycle of Fuji views—which would expand to 146—began in 1830 when Hokusai was 70 and continued until his death at 88. In the first plate of his second series, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, the mountain’s patron Shinto goddess, Konohanasakuya-hime, rises from the chaos and mists of antiquity. She embodies the center of the universe, emerging from the earth during a single night. Hokusai shows us glimpses of Fuji from a tea plantation, a bamboo grove and an old tree stump, framed by cherry blossoms, through a trellis, across a rice field, in a snowstorm, beneath the arch of a bridge, beyond an umbrella set out to dry, as a painted screen in a courtesan’s boudoir, cupped in the claw-like fume of a wave reaching its grip over fishing boats.

Of Hokusai’s hidden agenda, the pre-eminent East Asian scholar Henry D. Smith II, now professor emeritus of Japanese history at Columbia University, notes: “By showing life itself in all its shifting forms against the unchanging form of Fuji, with the vitality and wit that informs every page of the book, he sought not only to prolong his own life, but in the end to gain admission to the realm of Immortals.”

**********

Straddling the border of the Shizuoka and Yamanashi prefectures, Fuji-san is not only the source of the ultimate mystical journey in Japanese culture; it’s also the focus of a substantial national rumpus. Pristine and starkly beautiful as it appears from afar, the magic mountain is entangled in a multitude of contemporary predicaments.

To the dismay of the local community, the vast sea of trees engulfing the northwest foot of Fuji, Aokigahara, may have become the world’s most popular suicide spot, far eclipsing sites like the Golden Gate Bridge. Though posted trail signs in Japanese and English bear encouraging messages along the lines of “Your life is a precious gift from your parents,” and “Please consult the police before you decide to die,” hundreds of bodies have been recovered since patrols began in 1971. An astonishing 105 suicides were confirmed in 2003, the year that officials—in an effort to deter the determined—stopped publishing data. Aokigahara is a disorienting place where sunlight seldom reaches the ground, and the magnetic properties of iron deposits in the soil are said to confound compass readings. Fueled in part by a popular crime novel, Seicho Matsumoto’s Tower of Wave, distraught teens and other troubled souls straggle through the 7,680-acre confusion of pine, boxwood and white cedar. In the eerie quiet, it’s easy to lose your way and those with second thoughts might struggle to retrace their steps. According to local legend, during the 1800s the Japanese custom of ubasute, in which elderly or infirm relatives were left to die in a remote location, was widely practiced in the Aokigahara. Their unsettled ghosts figured prominently in the plot of The Forest, a 2016 American horror film inspired by the Japanese folklore of yurei—phantoms experiencing unpleasant afterlifes.

In Aokigahara, you can’t see the forest for the trees; in Tokyo, you can’t see the mountain from the street. A century ago, 16 hills in the city were affectionately categorized as Fujimizaka (the slope for seeing Mount Fuji), all offering unobstructed views of the volcano. But as high-rises and skyscrapers climbed into the sky in postwar Japan, street-level perspective was gradually blocked out and vistas vanished. By 2002, the slope in Nippori, a district in the Arakawa ward, was the last in the central city to retain its classic sightlines to the mountain, a breathtaking panorama immortalized by Hokusai.

A few years back, over strenuous public protests, that vantage point was overtaken. An 11-story monstrosity—an apartment building known as Fukui Mansion—went up in the Bunkyo ward. “Bureaucrats were reluctant to infringe on property rights, and feared loss of tax revenue from redevelopment,” reports urban planner Kazuteru Chiba. “Tokyo’s approach to planning has been to build first and worry about beauty and preservation later.” Which is how, in Japan, scenic inheritances become distant memories.

The hottest issue currently embroiling Fuji is the volatility of the volcano itself. Fuji-san has popped its cork at least 75 times in the last 2,200 years, and 16 times since 781. The most recent flare-up—the so-called Hoei Eruption of 1707—occurred 49 days after an 8.6 magnitude earthquake struck off the coast and amped up the pressure in the volcano’s magma chamber. Huge fountains of ash and pumice vented from the cone’s southeast flank. Burning cinders rained on nearby towns—72 houses and three Buddhist temples were quickly destroyed in Subasiri, six miles away—and drifts of ash blanketed Edo, now Tokyo. The ash was so thick that people had to light candles even during the daytime; the eruption so violent that the profile of the peak changed. The disturbance triggered a famine that lasted a solid decade.

Since then the mountain has maintained a serene silence. It’s been quiet for so long that Toshitsugu Fujii, director of Japan’s Crisis and Environment Management Policy Institute, quotes an old proverb: “Natural calamities strike about the time when you forget their terror.” Several years ago a team of French and Japanese researchers warned that a sharp increase in tectonic pressure from the massive earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan in 2011 and caused the Fukushima nuclear plant meltdown had left the country’s symbol of stability ripe for eruption, a particular worry for the 38 million citizens of Greater Tokyo.

With that in mind, Japanese officials have adopted an evacuation plan that calls for up to 750,000 people who live within range of lava and pyroclastic flows (fast-moving currents of hot gas and rock) to leave their homes. Another 470,000 could be forced to flee due to volcanic ash in the air. In those affected areas, wooden houses are in danger of being crushed under the ash, which becomes heavy after absorbing rain. Winds could carry the embers as far as Tokyo, paralyzing the country’s capital. A large-scale disaster would force closure of airports, railways and highways; cause power outages; contaminate water; and disrupt food supplies.

In 2004 the central government estimated economic losses from an immense eruption at Fuji could cost $21 billion. To monitor the volcano’s volatility, seismographs, strainmeters, geomagnetometers, infrasonic microphones and water-tube tiltmeters have been placed on the mountain’s slopes and around its 78-mile perimeter. If tremors exceed a certain size, alarms sound.

Still, Toshitsugu Fujii says we have no way of knowing exactly when the sleeping giant might be ready to rumble. “We lack the technology to directly measure the pressure in a body of magma beneath a volcano,” he says, “but Fuji-san has been napping for 310 years now, and that is abnormal. So the next eruption could be The Big One.” He puts the likelihood of a major blow within the next 30 years at 80 percent.

Not least, the degradation of Fuji has come from simply loving the 12,388-foot mountain to death. Pilgrims have scaled the rocky paths for centuries, though women have been allowed to make the ascent only since 1868. Supplicants chant “Rokkon shojo” (“Cleanse the six sins, hope for good weather”) as they climb, and seek the power of the kami to withstand the hardships of mortal life. These days, the base of Fuji teems with a golf course, a safari park and, most jarring of all, a 259-foot-high roller coaster, the Fujiyama. Each summer millions of tourists visit the mountain. Most are content to motor halfway to the fifth station and turn back. Beyond that point, vehicles are banned.

Modern Japan is a risk-averse society and climbing up the volcano is a hazardous undertaking. The ascent isn’t technically challenging—more like backpacking than mountaineering—but the terrain is unexpectedly treacherous, with fiercely fickle weather, high winds and, on occasion, attendant casualties. Of the 300,000 trekkers who in 2015 attempted the climb, 29 were involved in accidents or were rescued due to conditions including heart attacks and altitude sickness. Two of them died.

It was on a mild summer day, with only a gentle zephyr to dispel the fog, that I tackled Fuji. Most of my fellow hikers began their six- or seven-hour ascents in late afternoon, resting at an eighth station hut before setting off just after midnight to make sunrise at the pinnacle. In lieu of a keepsake “My Dad Climbed Mount Fuji and All I Got Was This Lousy T-Shirt,” I brought home a wooden climbing stave that, for 200 yen ($1.77) apiece, I had validated at every upper station. When I got home I displayed the stamped stick prominently in my office. It failed to impress anyone and is now wedged behind a can of motor oil in the garage.

In June of 2013, Unesco, the United Nation’s cultural arm, designated the mountain a World Heritage site—recognizing the peak as a defining symbol of the nation’s identity—and more or less sanctifying the climb as a bucket-list experience. In part to qualify for this prestigious listing, both Shizuoka and Yamanashi introduced a 1,000 yen ($8.86) entrance fee that helps fund first-aid stations and remediate damage inflicted by hikers. The mass of upwardly mobile humanity leaves an avalanche of trash in its wake, a national embarrassment. “The Unesco designation essentially created two schools,” American expatriate Jeff Ogrisseg observed in a posting on the website Japan Today. The first, he wrote, is comprised of pipe-dreamers who “thought that the World Heritage status would magically solve the problem.” The second is made up of “knuckleheads who think that paying the climbing fee would absolve them from carrying away their trash (which used to be the guiding principle).”

**********

The sudden double-clap of hands—a kashiwade to summon and show gratitude to the Yasukuni spirits—ricochets through the serenity of the Fujiyoshida Sengen Shrine like a gunshot. Wearing a billowing robe, straw sandals and split-toed ankle-high socks, a Shinto priest pays homage to Konohanasakuya-hime. Pray to the goddess and she may keep the holy peak from blowing its stack. A wind springs up, a strong gust that carries the pungent scent of pine needles. The priest, sandals slapping, heads down a lane lined with stone lanterns and towering cryptomeria trees to a gateway, or torii, that bears the mountain’s name. The torii, which marks the transition from the profane to the holy, is dismantled and rebuilt every “Fuji Year” (six decades). Built on the slopes of the volcano and moved to the lowlands in 788 to keep a safe distance from eruptions, Fujiyoshida Sengen is a traditional starting point for Fuji pilgrimages.

After passing through the torii, early wayfarers began their 10.6-mile climb up a path with widely spaced steps and sandy switchbacks, the Yoshidaguchi Trail, to the very lip of the crater. If ancient literature and painting are to be believed, the first ascents were nonstop sixth-century flights on horseback taken by Prince Shotoku, a member of the Imperial Clan and the first great Japanese patron of Buddhism. On the other hand, Nihon Hyaku-meizan (100 Famous Japanese Mountains), a Japanese climber’s paean to the country’s peaks, published in 1964, records a magical solo shuttle to the summit in 633 by En no Gyoja, a shaman credited with founding Shugendo, the way of mastering mysterious power on sacred mountains. By the Muromachi period (1333 to 1573), two walking routes to the peak had opened—the Yoshida and the Murayama—and true believers were making regular ascents, usually after visiting one of the temples at Fuji’s southern foot.

It wasn’t until the appearance of the peripatetic ascetic Hasegawa Kakugyo in the 15th century that the climb became popular. His disciples encouraged the common people—farmers and townsfolk—to join Fuji-ko. Following hidebound ritual, devotees today embark on annual pilgrimages during July and August, having undergone mental and physical purification before making the climb to the summit. Scaling the mountain signifies rebirth, a journey from kusayama, the mundane world, to yakeyama (literally, “burning mountain”), the domain of the gods, Buddha and death. Early wanderers revered every step as they passed the ten stations along the route. That’s not quite the deal now; most hikers prefer to start at the 7,600-foot fifth station, where the paved road ends. Since Fuji is covered in snow much of the year, the official climbing season is limited to July and August when conditions are less dicey.

Today, the fifth station is a tourist village that might have been modeled after Tokyo Disneyland. At high season, the concourse is virtually impassable, thronged by masses of single-minded shoppers foraging through tables and bins heaped with curios. Stations at higher elevations have inns where you can eat and buy canisters of oxygen. At night, the lodges pack in climbers as densely as commuters in the Tokyo subway. Eight wireless internet hotspots have been activated on the mountain. “Free Wi-Fi?” wrote one commenter on the Japan Today website. “Sorry, but the entire point of nature is not to be connected to the internet.”

**********

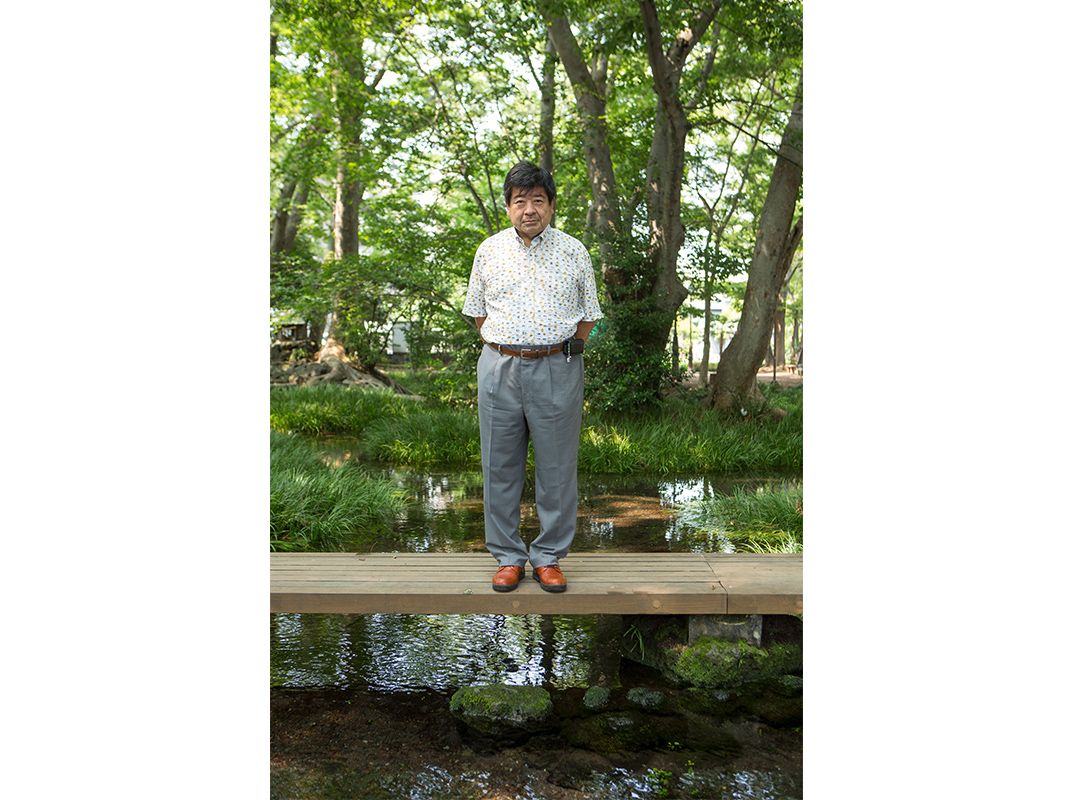

There’s a Japanese adage to the effect that Fuji should be climbed once in every person’s lifetime. The corollary is that anyone who does it more than once is a fool. Toyohiro Watanabe has ascended Mount Fuji 83 times—an even dozen in 2001, when he helped install the mountain’s first composting toilets—a project that was anything but a fool’s errand. The 66-year-old Watanabe, a roundish fellow who talks in a kind of sardonic rumble, walks with all the grace of a sake barrel. The Fujian equivalent of John Muir, he has launched four nonprofits to conserve and reclaim the environment of the volcano.

At Tsuru University, where he has taught sociology, he pioneered the field of “Fuji-ology.” He lectures on the mountain’s greenery and culture, and requires his students to collect rubbish at the site. “Fuji-san is representative of the environmental problems in Japan,” he says. “Through hands-on learning activities, I have established a new area of study centered on Mount Fuji.”

Watanabe grew up in Mishima, known as the City of Water, because it collects much of Fuji-san’s meltwater runoff. In 1964, enchanted by the otherworldly sublimity of the mountain, Watanabe made his first solo climb. Starting on the shore of Suruga Bay, he filled a jug with saltwater and ambled 30 miles to the summit, where he poured out the contents and bottled the melted snow. Then he lugged the jug of brine back down and poured it into a pond on the grounds of a Shinto shrine. “I wanted to show my appreciation to the mountain gods,” Watanabe recalls.

The land underlying northern Mishima is a field of lava. Groundwater seeps through cracks and fissures in the porous volcanic soil, gushing forth to form springs and the Genbe-gawa River. When Watanabe was growing up, children frolicked in the shallows of the Genbe. But by the late 1960s, development began to encroach on the base of Mount Fuji. Forests were leveled for resorts, factories and housing. Industries pumped water from underground reservoirs, and less and less reached Mishima. “The little that did was polluted by trash and residential wastewater,” Watanabe says. “The Genbe was as filthy and stinking as a gutter.”

In 1992, Watanabe spearheaded Groundwork Mishima, an initiative intended to reclaim and restore the Genbe. “Even the hearts of local citizens had begun to overflow with waste,” he says. “I’d see them brazenly litter as we cleaned up the aquatic environment—an affront to the mountain kami.” Watanabe has leaned on the private sector and government agencies for financial support, and also assembled specialists with a comprehensive knowledge of ecosystems, civil engineering and landscape gardening. Part of the funding was used to build a riverbank promenade featuring steppingstones and boardwalks. Today, the waters of the Genbe run as clear as a perfect dashi broth.

Back then, Watanabe campaigned for the mountain to be named a World Heritage site, but his efforts failed because the U.N. raised concerns about environmental degradation, notably visible in debris left behind on Fuji by hikers and motorists. Pathways were strewn with discarded oilcans and car batteries, broken office furniture and TV sets. Even rusting refrigerators. “Fuji-san was not just the mountain of fire,” Watanabe says. “It was also the mountain of garbage.”

At the end of each climbing season, raw sewage from the mountain’s outhouses was flushed down the rock face, leaving a stench in its wake. In 1998, Watanabe founded the Mount Fuji Club to conduct cleanup campaigns. Each year up to 16,000 volunteers join the periodic, all-day efforts.

The volume of debris hauled away by the litter brigades is stupefying: more than 70 tons in 2014 alone. The civic organization has also helped to remove bur cucumbers, a fast-growing invasive plant species, from Kawaguchiko, one of the lakes in the Fuji Five Lakes region.

The club’s greatest achievement may have been its advocacy for “bio-toilets,” packed with chipped cedar, saw dust or other materials to break down waste. Forty-nine have been installed near mountain huts, at a cost of one billion yen ($8.9 million). But the units have begun to fail. Replacement will be expensive. “So who’s going to pay?” Watanabe asks.

Some of the $630,000 in tolls collected in 2015 went toward park ranger salaries. For now, the Ministry of the Environment employs only five rangers to patrol the Fuji national park’s 474 square miles.

Watanabe says that’s not enough. He also wants the number of climbers reduced from 300,000 annually to a more sustainable 250,000. While government officials in Shizuoka seem amenable, their counterparts in Yamanashi, whose trail sees two-thirds of the foot traffic, fear that fewer visitors would hurt tourism. A quarter-million locals earn their living from Fuji-related sightseeing. “Yamanashi actually encourages more climbers,” Watanabe says. His objections have not gone unheeded. Local prefectures recently established guidelines for hikers who scale Fuji out of season. Climbers now are encouraged to submit plans in writing and carry proper equipment.

Watanabe has called for creation of a Mount Fuji central-government agency that would be charged with putting together a comprehensive preservation plan for the volcano. He frets about the potential impact of acid rain-carrying emissions from coastal factories. “Fuji has a power all its own,” he says. “Yet it is getting weaker.”

Not long ago, Japan was rocked by the discovery of graffiti on boulders at several locations on the peak. One splotch of spray-paint prompted a horror-struck headline in the daily newspaper Shizuoka Shimbun: “Holy Mountain Attacked.” Watanabe was less disturbed by vandalism than by the excrement visible along the trail. Rudeness enrages Fuji, says Watanabe. “How long before the kami are so insulted that the volcano explodes?”

Of all the gods and monsters that have visited Fuji, only Godzilla is unwelcome there. In obeisance to the etiquette of destruction observed in films featuring the legendarily overgrown lizard, Fuji’s summit is treated as a national treasure to which the alpha-predator is denied access. Godzilla has clomped about the lower slopes in several movies—and another accidental tourist, King Kong, was dropped on his head during an aborted ascent—but Godzilla has never conquered Fuji. Here’s what he’s been missing:

On this brisk midsummer morning you’re trekking far above an ugly gash on the mountain (the parking lot), and continuing to climb. While confronting the Zen of pure exhaustion, you climb into the stark wasteland that transfixed Basho and Hokusai. It’s still there: In the sudden and swirling haze, clouds engulf the path and fantastically gnarled pines rise out of the fog like twisted, gesturing spirits. Perhaps this is why Fuji feels strangely alive. Basho wrote:

In the misty rainMount Fuji is veiled all day —How intriguing!

**********

You’re channeled up a trail cordoned off by ropes, chains and concrete embankments. The hikers are so bunched up that, from above, they look like a chain gang. Some wait in queues for hours as the path bottlenecks toward the summit. Three years ago Asahi Shimbun reported: “Before dawn, the summit is so crammed with hikers waiting for the fabled view of sunrise that if even one person in the crowd took a tumble, a large number of people might fall.” To the east, you see the palest smudge of light. To the west, hardened lava flows envelop the base of boulders, some of the rocks as big as houses.

Behind you, the faint tinkling of prayer bells. Much later, in the gloaming, you look down and see a long, bobbing thread of lanterns and straw hats—pilgrims shuffling ever-skyward to keep divine wrath from befalling their community. Hours of muddling through the volcanic wilderness leads to the hallowed ground of the summit, the very altar of the sun.

Statues of snarling lion-dogs stand sentry at the stone steps. You plod through the wind-weathered torii, and trudge past vending machines, noodle shops, souvenir stalls, a post office, relay towers, an astronomical observatory. Perched on the mountaintop, the detritus of civilization seems a sacrilege.

Eventually, you lumber to the lip of the yawning rust-brown crater. Buddhists believe that the white peak signifies the bud of the sacred lotus, and that the eight cusps of the crater, like the flower’s eight petals, symbolize the eightfold path: perception, purpose, speech, conduct, living, effort, mindfulness and contemplation.

Followers of Shinto hold that hovering above the caldera is Konohanasakuya-hime (“She who brought forth her children in fire without pain”), in the form of a luminous cloud, while the goddess’s servants watch and wait to hurl into the crater whoever approaches her shrine with an impure heart. Sulfur venting from the caldera taints the cold air and stings your nostrils. On opposite sides squat two concrete Shinto shrines strung with glistening totems and amulets that climbers have left behind as good luck talismans. The rim is lined with couples holding hands and brandishing smartphones on selfie sticks. “Banzai!” (“Ten thousand years of long life!”), they shout. Then they shamble off to slurp ramen in the summit cafeteria.

At daybreak, you stake out ground on a lookout and watch the rising sun burn off the clouds. In the thin air you can make out Lake Kawaguchiko, the Yokohama skyline and the endless sprawl of Tokyo. If you stand and concentrate very, very hard you can conjure a vision of Ejiri in Suruga Province, a Hokusai view with Fuji in the background, majestically immobile, simplicity itself, the constant divine. You imagine Hokusai’s travelers in the foreground—caught by a whoosh of wind on the open road, holding onto their hats, bending into the gust as fluttering sheets of paper escape from a woman’s kimono and whirl over a rice field.

The mountain begins to feel mysterious again.

Mount Fuji: Icon of Japan (Studies in Comparative Religion)