Japan’s Most Mouthwatering Dishes Are Made of Plastic

Discover sampuru, the art of mind-blowingly realistic fake food

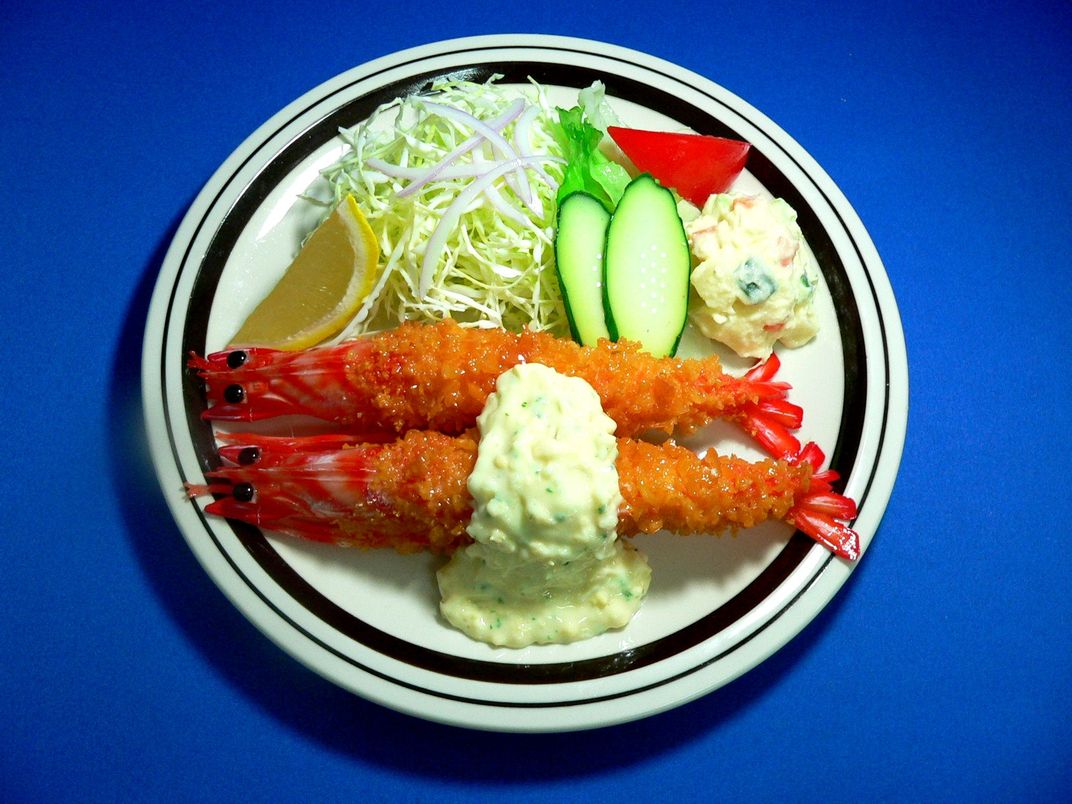

Walk down any street in any city in Japan and you'll see them: Mouthwatering plates of food in what can seem like every shop window, beckoning you into restaurants that sell everything from ramen to pastries. They never go bad, but don't take a bite. It's likely that the food you see isn't food at all—rather, it's a clever plastic recreation of the delights to be found inside.

Japan's fake food, or sampuru, revolution began in Gujo Hachiman, about three hours from Tokyo. It all started in 1917, when businessman Takizo Iwasaki was struck by inspiration. The legend is up for debate, but at some point Iwasaki witnessed either a wax anatomical model or candle drippings on a table and became obsessed with the lifelike potential of wax. He was inspired to begin an advertising company for food products—but without the food. Rather, every item inside would be made out of wax. Soon, Iwasaki was making models and selling them to restaurants and grocery stores as examples of the food on sale.

No more guessing what a menu item might look like—or even reading a menu at all. Later, during the reconstruction period after World War II, the models proved invaluable for American soldiers who couldn’t read restaurant menus. All they had to do was point at what they wanted from the sample selection and get ready to dig in to the real thing.

Today, about 80 percent of the nation's sampuru is still made in Gujo Hachiman. The materials have changed—wax had a habit of melting in Japan’s hot sunlight—but the idea remains the same: Intricately decorated food models line restaurants and department store shelves, showing exactly what the food looks like and helping people who don’t speak the language decide what to eat. The fake food has even taken on a life of its own. Tourists can buy elaborate models to bring home and purchase mouthwatering fakes on everything from keychains to iPhone cases.

Japan’s plastic food makers remain faithful to the original recipe, often “cooking” the plastic like they would cook real food. Sets of kitchen knives cut plastic vegetables, plastic fish is skillfully pressed onto fake rice balls held together with adhesive and real spices are even added to some finished products to make them look more realistic.

There's a reason the food looks so real: It's entirely based on the real thing. Restaurants and other vendors shilling food send photos and samples of their foods to the producer of their choice, who then makes silicone molds of each product. The items that don’t need to be painstakingly handcrafted are formed in the molds and painted—all by hand. Everything else is made out of melted color plastic or vinyl. The hot liquid is poured into warm water and shaped by hand, with paints and markers used to add the finishing touches. Some items, like cakes, even have melted plastic piped on to look like icing.

“People ask me, can’t I learn from the craftsmen?” Justin Hanus, owner of Fake Food Japan in Osaka, told Smithsonian.com. “People don’t understand that to learn this art, it takes years of training. It’s like an apprenticeship. If you were to be an apprentice, you’re looking at least at three years, but five years to be at the level deemed to be quality they would accept.”

That's a little better than the ten years it takes to be a sushi chef, but hey, it’s plastic food. And it’s food that lasts—Hanus says one sample piece can last for about seven years.

To put your plastic crafting skills to the test, head to Fake Food Japan in Osaka or Ganso Sample in Kappabashi, Tokyo. Both locations offer one-off classes and workshops for budding fake food artists. Or simply wander the dining districts of any city in Japan, and let the artificial whet your appetite.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)