From Bottles to Newspapers, These Five Homes Were Built Using Everyday Objects

Open for visitors, these houses model upcycling at its finest

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/88/a5/88a56c27-e047-4406-b25e-49559f7505d4/pbv8.jpg)

Could bricks, wood and stucco be building materials of the past? By touring one of these five homes built using everything from stacks of yellowed newspapers to flattened beer cans, you might just become a believer in the power of upcycling.

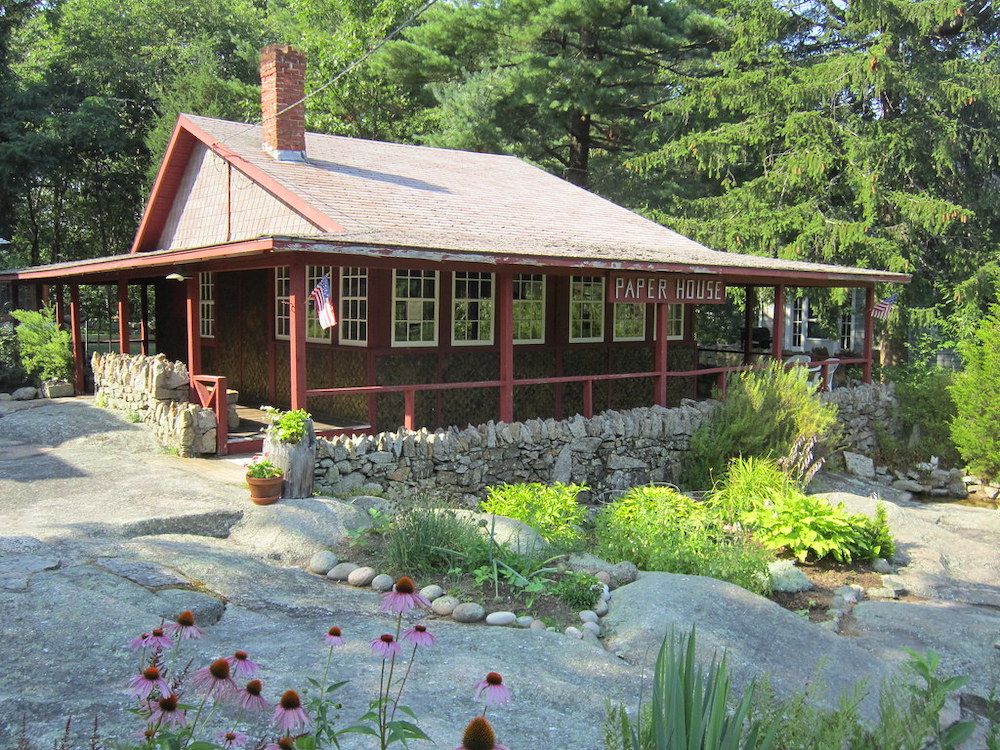

The Paper House, Rockport, Massachusetts

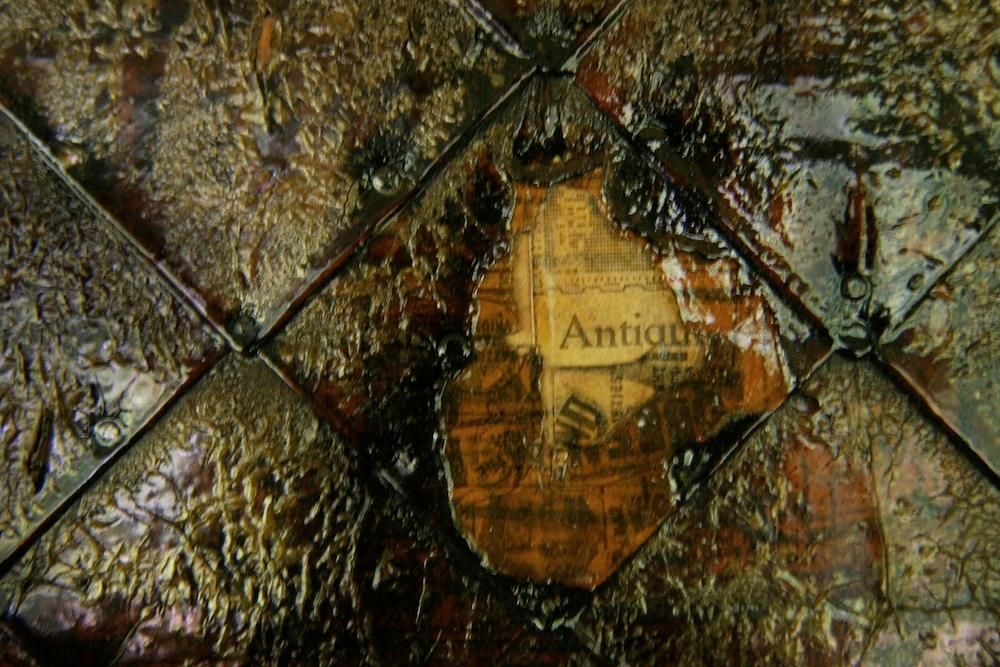

When Elis F. Stenman, a mechanical engineer who also happened to be the designer of the machine used to manufacture paper clips, built his summer home in 1922, he turned to paper as the perfect material to provide insulation. Armed with buckets of glue and varnish, along with towers of newspapers he had collected, Stenman portioned one-inch-thick segments of newsprint, which he jury-rigged together and inlayed between the home’s wood framework and roof. The design has proven to be quite waterproof, as it's still standing nearly 100 years later. In fact, the newspapers were so durable that Stenman decided to make furniture for the home out of them, rolling stacks of newsprint into logs to form tables and chairs.

In an interview published in the Cape Ann Sun in 1996, Edna Beaudoin, the home’s current caretaker and Stenman’s niece, said that no surface was safe from being plastered in paper. “When he was making the house here, he just mixed up his own glue to put the paper together. It was basically flour and water, you know, but he would add little sticky substances like apple peels,” she said. “But it really has lasted. The furniture is usable—it's quite heavy. Basically the furniture is all paper except for the piano, which he covered.”

The home has been open to visitors since the 1930s, and only began charging admission (10 cents per person) in 1942 when it became a museum. Today visitors can experience the Paper House for themselves for $2 for adults and $1 for children, and even catch up on the news of yesteryear, as the owner purposely made it so that the papers he used remained legible. One popular headline that people look for states, "Lindbergh Hops Off for Ocean Flight to Paris."

Beer Can House, Houston

After guzzling down an ice-cold beer, most people pitch empty cans into the nearest recycling bin, but not John Milkovisch. Instead, the retired Southern Pacific Railroad employee decided to use what he saw as prime building material for a home. He began construction in 1968, and for the next 18 years amassed more than 50,000 beer cans, which he collected himself (he hated being wasteful) and flattened to create aluminum siding for his approximately 1,300-square-foot Beer Can House in Houston. Milkovisch wasn’t choosy about what brands of beers he used, once saying that his favorite beer was “whatever’s on special.” And nothing went to waste. After accumulating thousands of beer can tabs, he strung them together like “people string popcorn on a thread” to create curtains and fringe for the home.

The Beer Can House was acquired by The Orange Show for Visionary Art, a non-profit foundation focused on preserving out-of-the-box creations like Milkovisch’s impressive nod to the benefits of recycling, after his wife's death in 2002. Today the home is open to visitors on Saturdays and Sundays (there are extended dates during the summer), and admission is $5 for adults, children 12 and under are free.

Plastic Bottle Village, Bocas del Toro, Panama

According to the website for the Plastic Bottle Village in Panama, “one man’s trash is another man’s condo.” Truer words could not describe Robert Bezeau’s project, which began in 2012, when he spearheaded a recycling program for Bocas del Toro, a province consisting of a portion of the mainland and islands in northwest Panama. (The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute has a research station less than two miles south of Plastic Bottle Village.) After accumulating tens of thousands of bottles discarded along city streets and beaches, Bezeau decided to put the plastic refuse to good use and recruited a team of locals to construct a building using the unwanted material, caging the bottles into metal “bricks” to build the structure. Realizing that they had more bottles than they needed, the group built a village, including a four-story castle made of 40,000 empty plastic water and soda bottles that is available for overnight stays and a dungeon comprised of 10,000 bottles where people can repent their own plastic waste crimes to the environment.

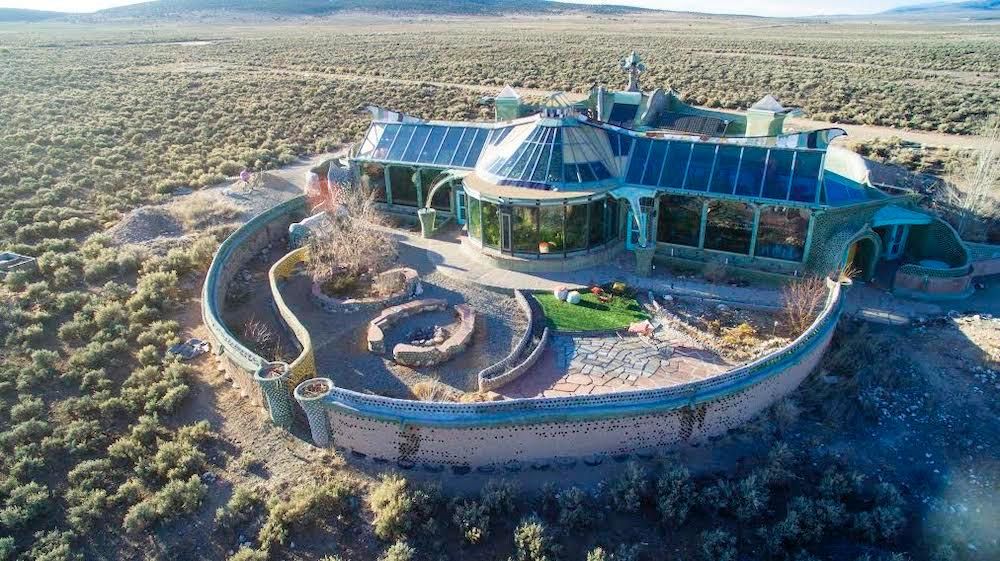

Earthship Biotecture, Taos, New Mexico

Mike Reynolds built his first Earthship when he was 23 years old. Fresh out of college, the future architect moved to Taos in the early 1970s to visit a friend and fell in love with the desert landscape, discovering that the dry climate would be ideal for his out-of-this-world idea: creating an Earthship. Starting out with nothing more than an empty six-pack of Schlitz beer and some adobe concrete, Reynolds set out to create a home that was not only sustainable and energy efficient, but also easy enough for someone without a construction background to build. In an interview published in the Taos News in 2017, the Earthship inventor said he was inspired by “piles of old tires” he would see around town, so he “filled them with rammed earth” and stacked them one on top of the other along with discarded tin cans and glass bottles to form structures. His idea caught on, and soon Earthships became a common site around Taos.

At its headquarters in Taos, Earthship Biotecture, an organization that promotes the construction of sustainable homes using materials that are readily available, offers nightly stays at some of its onsite Earthships, including the 5,300-square-foot Phoenix Earthship that is completely off the grid and resembles a greenhouse. Self-guided tours are also available through the Earthship Visitor Center.

The Bottle Houses, Cape Egmont, Prince Edward Island, Canada

A six-gabled house, a tavern and a chapel are three structures commonly found in villages throughout the world, but this cluster of buildings on Prince Edward Island is a bit different. Built out of approximately 30,000 glass bottles and held together using cement, The Bottle Houses are the creation of Éduoard T. Arsenault and his daughter Réjeanne. The duo began construction in 1980, inspired by a castle Réjeanne visited in Boswell, British Columbia constructed entirely of empty glass embalming fluid bottles. Over the months, the father and daughter collected empty bottles from local restaurants, dance halls, friends and neighbors, and by 1981 they opened the six-gabled house to the public. Inspired by the public’s interest, the pair built the tavern in 1982, which was followed by the chapel in 1983. Since then, the three buildings have remained open to visitors, with sunny days being the best time to visit. It’s then that the clear, green, blue and brown bottles create an awe inspiring “symphony of color and light,” according to its website.