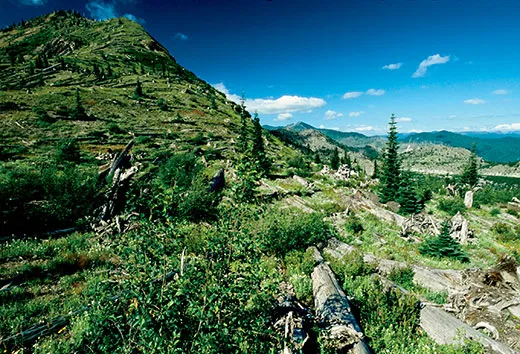

Evolution World Tour: Mount St. Helens, Washington

Over thirty years after the volcanic eruption, plant and animal life has returned to the disaster site, a veritable living laboratory

Catastrophic events shape evolution by killing off plant and animal populations and creating opportunities for new species. When Mount St. Helens exploded, scientists seized the opportunity to study the aftermath. “It’s been an ecologist’s dream to stay here for decades to watch how life reinsinuates itself onto a landscape that had been wiped clean,” says Charlie Crisafulli of the U.S. Forest Service, who has worked on the mountain since shortly after its eruption.

On May 18, 1980, at 8:32—a Sunday morning—the volcano set off the largest landslide in recorded history. Rock slammed into Spirit Lake, sending water up the hillsides and scouring the slopes down to bedrock. Another hunk of mountain spilled 14 miles down the North Fork Toutle River, burying the valley under an average of 150 feet of sediment. A blast obliterated, toppled or singed old-growth trees as far as 20 miles away. A column of ash soared 15 miles high, falling across 22,000 square miles. Flows of gas and rock at 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit surged down the slopes, incinerating all life in a six-square-mile area now known as the pumice plain.

Despite the devastation, Crisafulli says, some species hung on. Many nocturnal animals, such as mice and voles, remained in their underground retreats during the morning explosion. Several species of birds had yet to migrate to nesting sites in the area. Snow and ice protected some plants and aquatic species. Those biological holdouts—including organic matter from dead trees and insects that aid in soil formation—would lay a foundation for recovery.

The avalanche created hummocks and depressions that formed two lakes and 150 new ponds. Within a few years, the new bodies of water drew frogs and toads. Evidence of another survivor, the northern pocket gopher, could be detected by helicopter. “You could see these beautiful, deep dark rich forest soil mounds on top of this bleak, light gray ash,” says Crisafulli. As they burrowed, the gophers churned up plant debris and microbes essential for building soil. The mounds caught windblown seeds. And when returning elk stepped on gopher tunnels, they created amphibian refuges.

On the pumice plain, the pioneer species was a flowering legume called the prairie lupine, which added essential nitrogen to the heat-sterilized soil, enabling other plants to take root. Today, millions of lupine cover the pumice plain, along with penstemon, grasses, willows and young conifers.

Some 110,000 acres of the disturbed area are preserved in Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. It offers scenic overlooks, miles of trails, guided hikes and visitor centers to help understand and appreciate this living laboratory.