Colombia Dispatch 12: Still Striving for Peace

In spite of all the positive work that has done in recent years, there are concerns that the government may be cracking down too hard in the name of peace

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/wrapup_631.jpg)

In the nearly six weeks I spent criss-crossing Colombia on long bus rides, I was often amazed by the friendliness and optimism of its people. If I asked for directions, I was invariably accompanied to my destination to make sure I found it. A quick chat often evolved into a lively conversation and invitations to dinner or connections with friends in other cities. People told me how frustrated they were with the Colombian stereotype of drugs and violence, that most people lived normal lives and there is so much more to the country.

The steamy atmosphere and tropical rhythms of the Caribbean lowlands seems like a completely different country than the Andean chill of cosmopolitan Bogota. Each region has a distinct dialect, food, music and climate. Colombians everywhere are full of national and regional pride in their culture.

Many of those regions are now opening up, following the example of the recovery of once-deadly cities like Medellin. For many years, Colombians feared traveling long distances on highways, afraid of running into a rebel roadblock on an isolated stretches of road. Several times locals informed me that if I had traveled the same road a decade ago I could easily have been kidnapped.

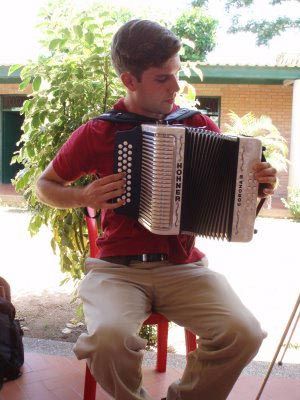

Now, frequent military checkpoints on roads, along with billboards telling the motorists they can "travel safely, the army is along the route," are the most visible remnants of the conflict where I traveled. In most of the areas I visited, the violence seemed to be happening in another world. Life goes on normally, from soccer matches on the beach to street parties in big cities that were full of musicians, jugglers and fire eaters.

Yet Colombia's battle with the cocaine trade and illegal armed groups is far from over. There still is social inequality, corruption, rugged and isolated geography and an established drug trade. While middle-class families live in comfortable homes and shop at Wal-Mart-style superstores, many of the republic's poor live in impoverished conditions and fear violence in remote rural areas. Even in the major cities, I heard reports of new brutal paramilitary groups like the "Black Eagles" in Bogota, formed in part by demobilized paramilitaries who regrouped.

The billions of dollars in U.S. aid given to Colombia to fight coca cultivation—much of it through controversial aerial fumigation—have not significantly slowed cocaine production. And the Colombian government is now investigating more than 1,000 possible "false positives," the chilling term for civilians killed by the military and presented as guerillas in an effort to pump up body counts. It's a serious blow to the credibility of the country's military, which receives strong U.S. support.

Reminders of the violence are still everywhere in Colombia. A frequent radio advertisement features a little boy listing the dangers or cocaine and marijuana and pleads with farmers not to "grow the plant that kills." Announcers at a soccer match read a public-service announcement telling guerillas that might be listening from their jungle camps "there's another life, demobilization is the way out!"

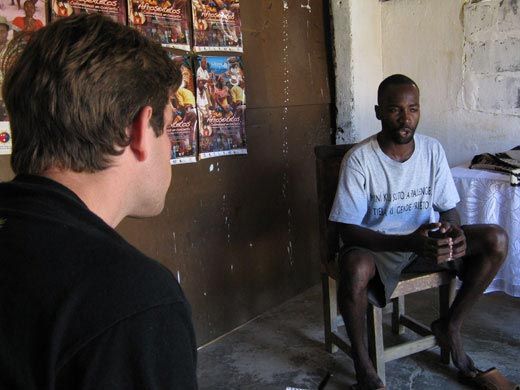

In recent years, Colombians have struggled to calm its decades-long conflict, and everywhere I went I met people working for peace. I arrived on July 20, Colombia's independence day, and crowds filled the streets of Cartagena to call for the release of the hundreds of hostages still being held by guerrillas. They all wore white T-shirts for peace, with slogans including "free them now" and "no more kidnappings." The scene was mirrored by hundreds of thousands Colombians in cities and towns across the country and worldwide in cities such as Washington, D.C. and Paris. It was a spirit I felt everywhere in country; that after years of conflict, people seemed ready for change.