An Exhibit in Illinois Allows Visitors to Talk with Holograms of 13 Holocaust Survivors

The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie, Illinois, opened the new Survivor Stories Experience this fall

Aaron Elster was 7 years old when the bombs came, thunderous airplanes whooshing over the Sokolow Ghetto in Poland, bringing destruction in their path. Three years later, he stood against a wall with his family—his parents, an older sister and his 6-year-old sister Sarah—waiting to be sent to nearby Treblinka, one of the Holocaust’s extermination camps, as the German army came to liquidate the ghetto. But he escaped, crawling to the edge of the ghetto, crossing the barbed wire border, and running for his life. He never saw most of his family again.

Elster’s sister also escaped, connecting with a Polish farmwife who hid her on the property. He was able to locate her and, after he had spent some time hiding outside in other local farms and stealing food, the bitter cold arrived, and he joined his sister there. For the next two years, Elster lived in the attic of that farmwife’s house. He never left the attic during that time, surviving on soup and a slice of bread once a day. He couldn’t bathe or brush his teeth, had no new clothes to change into and wasn’t allowed to make any noise. Covered in lice, he spent his days delousing himself in silence until the war ended, at which point he was transferred to a Polish orphanage. He and his siter were eventually smuggled out of Poland and headed to the United States.

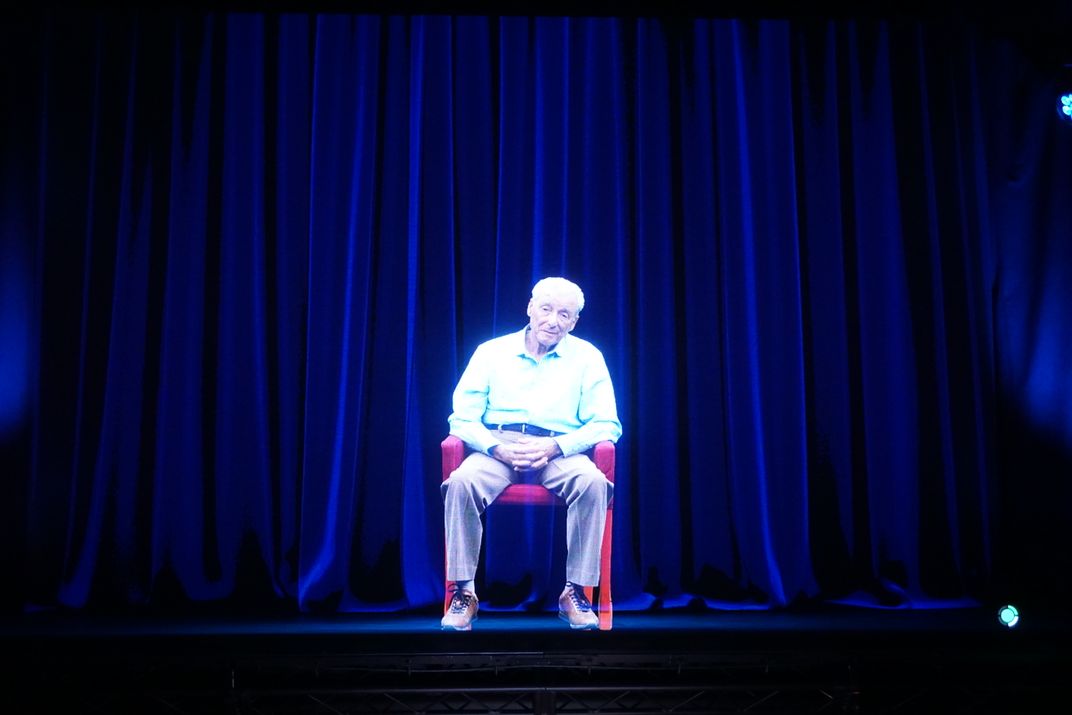

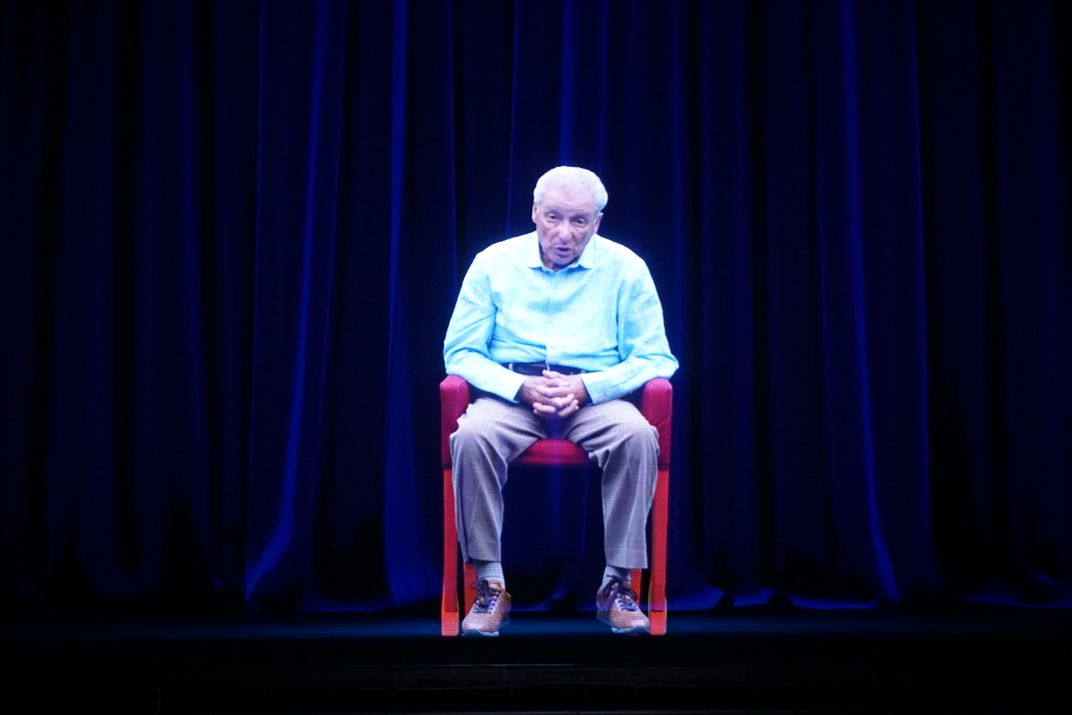

Now, Elster tells his story from the safety of the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center’s new Take A Stand Center in Skokie, Illinois—but he does so as a hologram. The Center opened to the public on October 29. Inside, it’s broken into three parts. Guests start in the Abe and Ida Cooper Survivor Stories Experience theater, where first-in-the-world technology allows visitors to interact with holograms of 13 Holocaust survivors, seven of which live in the Chicago area, including Elster. The survivors were filmed in 360 video with more than 100 cameras, a process that took about six days—all day—per survivor. They were asked around 2,000 questions each. The resulting holograms sit on stage in front of an audience, answering questions in real time about what their Holocaust experience was like.

“For me, talking about it was not that difficult,” Elster told Smithsonian.com. “I don’t know why, maybe my skin is too thick. But I know one of the people had to stop recording... Why would you want to stand in front of hundreds of guests and open up your heart and bleed in front of them? Because it’s important. This will exist longer than we will. And a whole new world of young people and adults will understand what people are capable of doing to one another, and that it just takes a little bit of goodness from each person to help change the world for the better.”

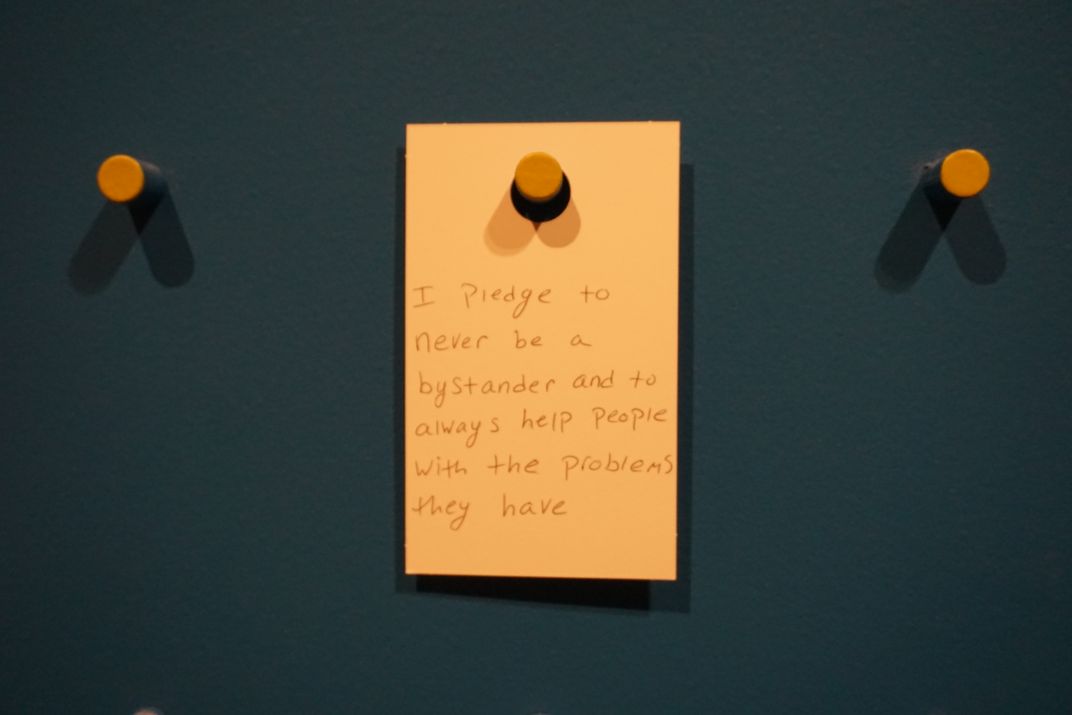

After a roughly half-hour hologram experience, guests move into the next part of the exhibit, the Upstander Gallery. Here, 40 people are featured as “upstanders,” those who are working hard to stand up for human rights and make the world a better place as a result. From there, guests move on to the Take a Stand Lab, a hands-on tool that helps anyone become an upstander themselves. The interactive Lab shows people different ways to take action, and then sends them home with a kit on how to actually do it.

The whole center took three years and about $5 million to create, but the jewel of the exhibit is the survivor experience. Before interacting with one of the survivors’ holograms, there’s a five-to-seven-minute video of that person relating their experience of survival through the Holocaust. As Elster watched his own video during the exhibit unveiling, he sat in the audience with tears in his eyes.

“I was sitting here listening to my own story that I’ve told 150,000 times, and suddenly I wanted to cry,” he said. “Sometimes I can just tell it like a story, and other times it becomes real. I’ve accepted the fact that my parents and my aunts and uncles were killed. But I had a little sister, Sarah, who loved me so much. I created this terrible image of how she died, and that causes me such pain. Do you have any idea how long it takes to die in a gas chamber? It takes 15 to 20 minutes before your life is choked out. Think about it. A 6-year-old little girl, people climbing on top of her in order to reach out for any fresh air that still exists in the room. They lose control of all their bodily functions and they die in agony. This is what you carry with you. It’s not a story. It’s reality.”

Another survivor, Sam Harris, described the experience of carrying thousands of bodies out of Auschwitz. "It’s impossible to believe, with what we went through, that we could still be here as human beings to talk about it," he said. "Maybe that’s why we were saved. As I watch [my portion of the experience], it brings back memories to my mind about what it was like. I was four years old when Hitler came. If I let myself go, this whole room would be flooded with tears.”

Both Harris and Elster agree that regardless of the emotions creating this experience brought back up, capturing these memories is vital to educating future generations about what happened during the Holocaust.

“When we’re gone, what happens next?” Elster said. “Do we become one sentence in the history of World War II? They killed Jews and that’s it? Or are we still alive, in essence, to tell people what happened, how they can help, how each and every one of them can make a difference. We keep saying ‘never again,’ but we have to remind the world what happened, and what could happen again, and why it shouldn’t happen to anybody. We’re still killing one another. So our hope is to make sure that young people understand what human beings are capable of doing to one another, and [that] we expect them to be upstanders. We expect them to make a difference, because they can."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)