Which General Was Better? Ulysses S. Grant or Robert E. Lee?

The historic rivalry between the South’s polished general and the North’s rough and rugged soldier is the subject of a new show at the Portrait Gallery

To showcase one of history's most memorable rivalries, the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery tasked its senior historian David C. Ward with the challenge of featuring the Civil War's two most storied generals in its "One Life" gallery. The one-room salon is the site where the museum's scholars have previously exhibited the portraits, letters and personal artifacts of such cultural luminaries as Ronald Reagan, Katharine Hepburn, Abraham Lincoln and Sandra Day O'Connor.

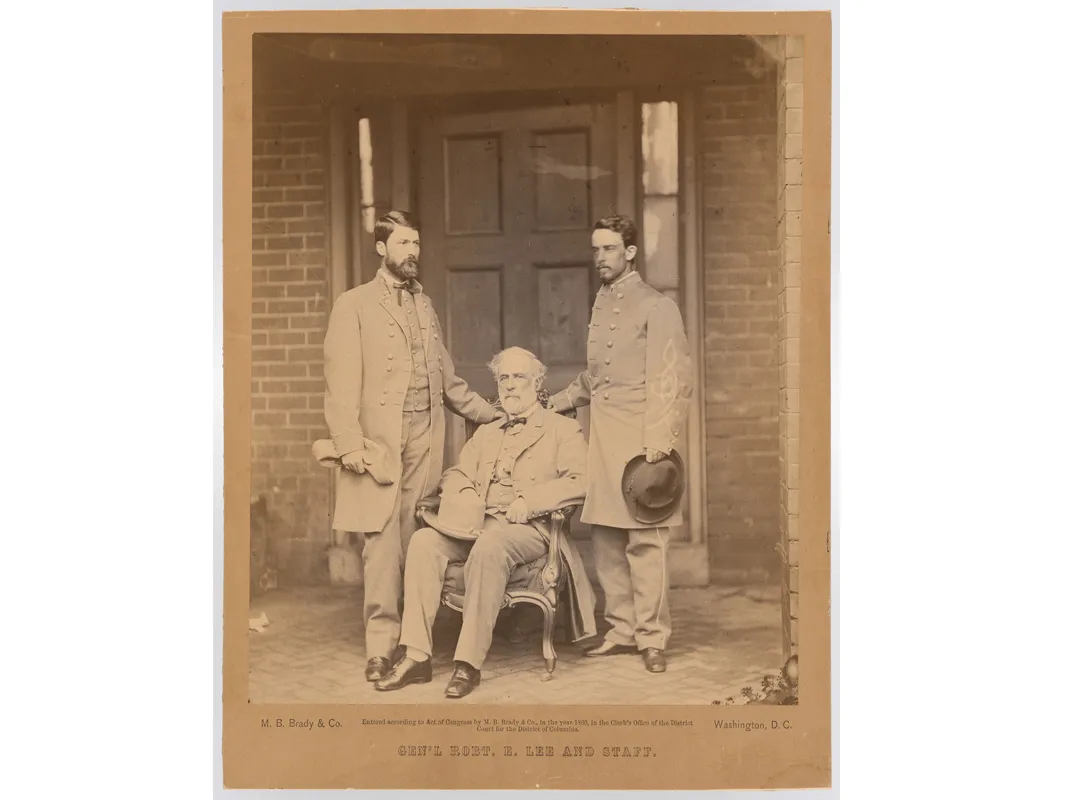

Here, the rough and tumble Ulysses S. Grant from Ohio faces off with the southern patrician Robert E. Lee. The room itself seems too small for such large personalities. The photographs, drawings and paintings depicting the lives of these two men seem to pulse with a kind of tension that recalls the horrifying 19th-century era when the country was riven, yet united behind their respective generals—Grant in the North and Lee from the South.

"They are products of their times," says Ward. "These men epitomized their societies." Grant is an unexceptional-looking tanner from Ohio—while Lee is "more patriarchical than the partriarch." The story of these men, their fallacies, their reputations, their legacies are well depicted in a number of art works, including the significant loan of a Winslow Homer painting titled, Skirmish in the Wilderness, from Connecticut's New Britain Museum of American Art.

But we asked curator Ward if he'd tell us who was the better general, and here is what he sent us.

The question has intrigued historians and armchair strategists since the Civil War itself. Lee is usually accounted the superior commander. He scored outrageous victories against the Army of the Potomac up until Gettysburg 1863, fighting against superior numbers and better supplied troops. His victory at Chancellorsville, where he divided his army three times in the face of the enemy while being outnumbered three to one, is a master class in the use of speed and maneuver as a force multiplier. Lee also had the difficult task of implementing a strategy to win the war that required him to invade the northern states, which he did twice. He knew the South couldn’t just sit back and hold what it had: the North was too strong and some sort of early end to the war had to be found, probably a negotiated peace after a shock Union defeat in Pennsylvania or Maryland. Lee also benefits from the cult of the “Marble Man” that arose after the War. With the southern ideology of the “Lost Cause” Lee, the heroic, self-sacrificing soldier, was romanticized as the exemplar of southern civilization. As such, Lee increasingly was seen as blameless or beyond reproach, which caused his mistakes or errors on the battlefield.

Conversely, Grant’s military reputation suffers from his reputation as president, which historically is regarded as one of the worst administrations of all. Grant’s haplessness as president has redounded to color his performance during the War. Grant’s personal charisma was never as high as Lee’s anyway; and he has been dogged by questions about his drinking. But taken on its own terms, Grant was an exceptional general of both theater commands, as in his seige of Vicksburg, and in command of all the Union armies when he came east. There was nothing romantic about Grant’s battles: he committed to a plan and then followed it through with an almost uncanny stubborness. He saved the Battle of Shiloh after the Union line was shattered on the first day, reorganizing his forces and counterattacking. “Whip ‘em tomorrow, though” he remarked to Sherman at the end of an awful first day’s fighting; and he did. His seige of Vicksburg was a remarkable campaign of combined operations with the “brown water” navy. And he was implacable in the final year of the war when he engaged Lee continuously from the Battle of the Wilderness to Appomatox.

I think that Grant slightly shades Lee as a commander because in the last year of the War he managed all of the Union armies, including Sherman in the South and Sheridan in the Shenendoah Valley. Grant served in the field, supervising Meade, who was still commander of the Army of the Potomac, but he had his eye on the entirety of the Union campaign. Moreover, Grant recognize the new reality of warfare: that the firepower commanded by each side was making a battle of maneuver, like Chancellorsville, impossible. Lee didn’t think much of Grant as a general, saying that McClellan was the superior foe. On the other hand, Lee beat McClellan. He didn’t beat Grant.

The exhibition, "One Life: Grant and Lee: 'It is well that war is so terrible. . .'" is on view at the National Portrait Gallery through May 31, 2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/fc/22fc67a2-a6a3-4b30-9e62-c5ddb101d07c/appottmax.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/7a/1d7ae2eb-5b55-4c9d-8b96-4cebbc7e75cc/grant1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/3f/bc3f3dbf-83ce-4f31-8187-d558d7c6b1fd/grant3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/2a/742a7ca9-26b6-4420-b1c2-736de8287ee6/grant4.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/db/d9dbd69b-fe7f-4a4a-8010-911e7832c710/lee1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/f5/56f5546a-742a-4bda-8464-6a591fc90527/lee2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/ad/9cadf123-f95d-4a32-8979-ed9466415a4c/lee3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/ad/22adc8a1-2298-4a39-afc9-e908c7934fc0/grant2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)