Unfolding the AIDS Memorial Quilt at the Folklife Festival

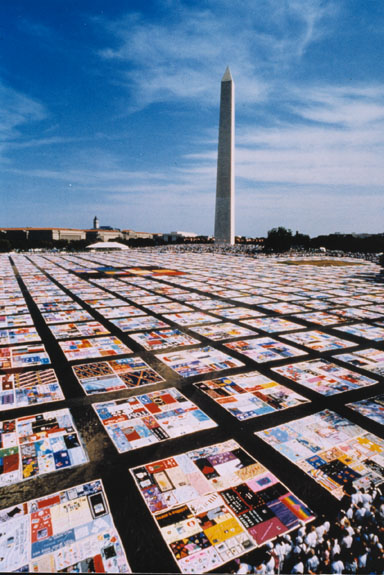

The AIDS Memorial Quilt, spread out on the National Mall. Image courtesy of The NAMES Project Foundation.

It would take more than 33 days to view the entire AIDS Memorial Quilt—if you spent only one minute per panel. The piece of community art, nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, remains the largest in the world.

The quilt was displayed for the first time on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. on October 11, 1987, during the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. It included 1,920 panels. Today there are more than 48,000.

The quilt has returned to our nation’s capital as a part of the 2012 Smithsonian Folklife Festival through July 8. The program, Creativity and Crisis: Unfolding The AIDS Memorial Quilt displays the patchwork of names and memories first thought up by the NAMES Project Foundation, an international organization that seeks to heighten awareness in the struggle to stop HIV and AIDS. We spoke with Julie Rhoad, president and CEO of the foundation, about how the quilt also managed to sew together a community for the past 25 years.

1) How did the idea to make the AIDS Memorial Quilt come about?

In 1985, people were rapidly dying from what was at that time not yet named HIV/AIDS. Family members and their friends in the Castro didn’t have a place to grieve. It was a very volatile time. The NAMES project founder, Cleve Jones, organized a march in 1985 where he asked his friends and family to carry placards with the name of somebody they had lost to this yet unnamed disease. When they got to the Federal Building at the end of the march, Cleve got some ladders and they taped the names up the side of the wall. When Cleve looked at it, he saw a quilt.

Two years later, when a small group of people got together to talk about HIV/AIDS, Cleve brought a three-foot by six-foot panel of cloth that had one of his dear friends’ name on it, and they realized it was time to form the NAMES project. We were founded in 1987 to make sure that people would be remembered and to make sure people would begin to talk about HIV/ AIDS in a different way—that these are real people who lived real lives and had people who loved them! As a result, it revolutionized the notion of quilting. Friends and family members began to make panels for their loved ones, growing to 1,900 total in the first few months. When the organization took them to DC and they laid the panels out on the Mall for the first time in 1987, people began to think ‘Oh my goodness, this is really not about statistics, it’s about people.’

2) What does it mean for the NAMES Project Foundation to bring the quilt back to DC?

I think 25 years ago we thought we’d be done with the disease within five years—that we’d be able to unhinge the panels, send them back to the panel makers and say ‘Here is your loved one’s panel. Care for it, we cared for it. It helped end AIDS.’ The same thing is true right now. We’re 25 years in, we have more than 94,000 names on this quilt and we’re not only one of the major symbols of the epidemic, we are also the evidence—we bear witness. So in a time, when science is saying that the potential exists for us to find a pathway to end AIDS, it’s imperative that we stand on our National Mall and tell people that this is about them. It’s about all of us.

3) How did you get involved with the organization?

In 1981 when the disease was first being identified, I was beginning a career in the professional theater and was witness to a community that was decimated by this disease. Thirty years ago HIV/AIDS became a part of my world and it has remained so because part of my world is now gone—a slew of friends are gone. I came to this from the arts community and it made sense for me to be involved in an artistic response like . To want to care for it, to make sure that in the foreseeable and the not foreseeable future that this quilt is always here to bear witness.

4) What might people coming to the Mall this year find on these panels?

I think each panel of this quilt is beautiful in its own way. I remember a panel maker said in one of their letters: ‘How does a mother, begin to sum up the life of her son in a three-foot by six-f00t piece of cloth?’ I think people will not only see a glimpse into a person’s life, but they will see how people loved them and how important they were. There are panels that have all sorts of things on them from flags to feathers to sequins; bowling balls, wedding rings, ashes, poems, photographs—all sorts of records of the person’s life. When you look at it from up close and personal, the intimacy and detail lovingly stitched into each one of these panels is evidence of love and life.

5) Do you have a personal connection to the quilt?

It’s personal the instant you begin to read one of the panels. All of a sudden it’s like you know a little bit about Bill Abbott, for example, because his leather jacket is here and there are pictures of his friends and family. You begin to know he was an artist. You know what size he was because of his jacket, that he was born in 1960. It’s a fascinating look at how valuable life is regardless of whether it’s a life that was lived for 30 years or 13.

6) At the Folklife Festival, there will be workshops for people to create their own panels. How will these events contribute to the message?

What happens around the quilting table, is kind of extraordinary. People may start the conversation by helping somebody make a panel and then discover after an hour or so together that a second person who’s come into the room is also there helping because they need to find a way to make a panel themselves. The dialogue begins and continues there.

7) What do you hope people will leave the festival thinking?

It would be interesting to see how people feel before they see it and after. We wonder about things: Does a piece of fabric carry the kind of weight of relevance that any other form of communication does? It’s such a pivotal time for HIV/AIDS in the world that when we look at how people responded and how they cared for one another through arts and culture as a communication tool, we realize is advocacy, it is art. We are coming to the Mall to say we are connected to one another as human beings—that we have a responsibility for one another.

Creativity and Crisis: Unfolding The AIDS Memorial Quilt program at the 2012 Smithsonian Folklife Festival is a partnership between the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and The NAMES Project Foundation, with the support and participation of many others. For a complete listing of events at the festival click here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)