In a Remote Amazon Region, Study Shows Indigenous Peoples Have Practiced Forest Conservation for Millennia

Smithsonian researcher Dolores Piperno says native people have always played an important role in sustainability

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/ed/c8ed063d-b8d2-4670-8f4a-bafbad111c29/untitled-1.jpg)

The Amazon, the world's largest and most biodiverse tropical forest, spanning nine countries and more than 2.3 million square miles, was once thought by scholars to hold untamed, unaltered, pristine wilderness.

However, the Amazon rainforest has long been home to many indigenous societies. In recent decades, researchers have found evidence of the many ways since prehistoric times that Indigenous peoples have shaped forest composition and its diversity, and domesticated native plants.

The human footprint in a number of regions is undeniable. Agriculture, fish weirs, roads, changes in soil composition and huge geometric earthworks called geoglyphs are evidence of the many ways Indigenous groups have had a significant impact.

Nevertheless, it is also becoming increasingly apparent that in some regions for thousands of years and into the present, the rainforest's native inhabitants have used forests in ways that didn’t much change them, leaving vast tracts of land little altered—no forest clearing and no agriculture with plants such as maize, squash, and manioc—indicating that in an anthropogenic age, humans have had little impact on these remote regions for as many as 5,000 years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/ca/0eca7caf-db73-4d35-8eee-3aaf4f99ab79/press_release_photo_2.jpg)

A new study, published in the journal Proceeding of the National Academy of Science and led by a Smithsonian researcher, proves that over millennia, a region of rainforest in the western Amazon shows no evidence of significant modification by Indigenous societies.

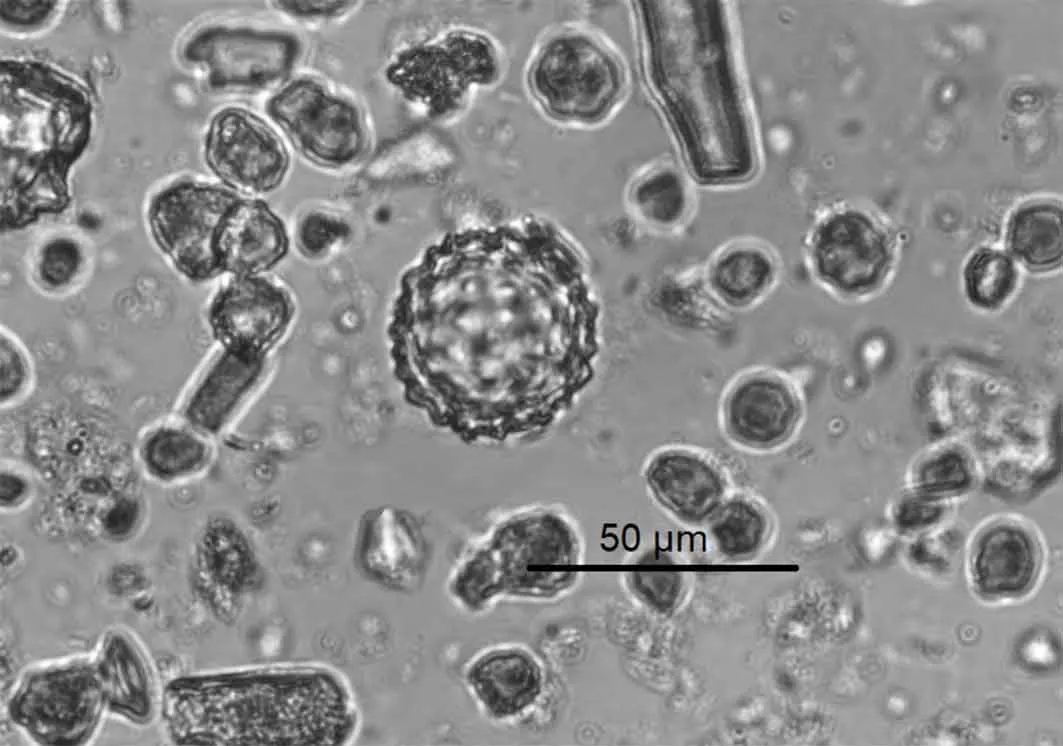

The study uses phytoliths, the microscopic silica bodies left behind by Neotropical plants after they decay, to determine what types of plants were growing at various periods, along with charcoal for the detection of the use of fire. Researchers working in the remote Putumayo region in northeastern Peru, collected soil core samples from three research campsites in the interfluvial areas, the forests located far from rivers and major tributaries, known as tierra firme.

“There have been a number of studies done by ourselves and others in the past decade or so, indicating little human modification of these interfluvial forests in western and central Amazonia during prehistory,” explains archaeobotanist Dolores Piperno, of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, who led the investigation. “So, this evidence is building,” she says.

Most of the significant human habitation and modification documented so far has been found around rivers and their tributaries, where the soils for plant cultivation and agriculture are more fertile and it's easier to find and catch game. The Indigenous communities that live along these riverbanks today practice subsistence agriculture in chacras—patches of land designated for growing food—and house gardens, they fish and hunt animals like peccaries and paca, and collect uncultivated products from the surrounding forests for food, medicine and other uses.

“Indigenous populations today and likely in the past were living in and exploiting the riverine forests just a few kilometers away from where we did our work,” says Piperno. But the nearby forests that are located further inland “appeared to have been much less impacted.”

Piperno says this study offers key insight into how to better protect these ecosystems. The 2019 wildfires, which devastated almost 3,500 square miles of rainforest, and which were exacerbated by the effects of climate change, only emphasized the fragility of the Amazonian ecosystems and reinforced the urgency for more effective action to preserve them.

“Indigenous people have always played a very important role in the sustainable use of the forest and the conservation of biodiversity, and they should continue to be central to it, especially because of their deep knowledge of the forest and its relevance in their daily lives,” Piperno says.

This study began five years ago, when Piperno’s co-authors, Nigel C. A. Pitman, Juan Ernesto Guevara Andino, Marcos Ríos Paredes, and Luis A. Torres-Montenegro, visited the unexplored area located between the banks of the Putumayo and the Algodón rivers, a forest characterized by gentle rolling terrain, tierra firme forests, peatlands and palm swamps. The researchers conducted an intensive core sampling of an area at the three research campsites, Quebrada Bufeo, Medio Algodón and Bajo Algodón, using an auger that drills out a column of soil about two to three feet long. They also conducted a botanical inventory, analyzing 1,300 species of plants and 550 species of trees.

The soil cores were sent back to the United States and Amsterdam to Piperno and ecologists Crystal McMichael and Britte Heijink, two other co-authors of the paper. Piperno performed the phytolith analysis, while McMichael and Heijink did the charcoal analysis, in their respective labs.

By documenting the vegetation and fire history, the researchers could better understand the level of human impact on the forest over the past 5,000 years. Phytolith and charcoal analyses were carried out on the ten soil cores collected. Phytoliths are used to identify different types of tropical vegetation, and charcoal fragments are evidence of fire.

“Phytoliths document well many important tropical flora, from weeds and other plants associated with human presences and disturbance to various kinds of forested vegetation,” says Piperno, who pioneered the development of the procedures for archaeological and vegetational history studies of phytoliths. Throughout her career, she has worked extensively analyzing these plant microfossils in archaeological sites in places like the Amazon and Central America tropics, highlighting their importance as tools to better understand the history of crop domestication and early agriculture.

“Phytoliths are very durable, and can be found where other plant remains are absent or poorly preserved,” says Daniel Sandweiss, a geoarchaeologist of the department of anthropology and the Climate Change Institute of the University of Maine, who was not involved in the study.

“They alone or with other plant remains, such as pollen and starch grains, have been used in a wide variety of studies, often to understand better what species people used in the past,” he adds, noting that Piperno is the world's leading expert on phytoliths in archaeology.

The phytoliths analysis indicated there was no detectable human influence on the diversity of species of plants and trees in these zones. That means there were no telltale signs of crops being grown, unlike the current areas of human settlements along the nearby rivers, where a number of plants, like maize, squash, manioc and various fruit trees are cultivated. Two kinds of palms that are important food sources and have been domesticated as a source of food in Amazonia were shown to not have increased over time, indicating that Indigenous peoples had not planted them or caused them to grow in any larger abundance in the tierra firme region.

Natural fires are rare in this region due to frequent precipitation; fires would have most likely been started by humans in order to clear areas for agriculture or for encampments or villages. Charcoal quantities in the same soil cores revealed that fires seldom occurred and were intermittent between the three campsites, indicating that over hundreds of years human-caused fires had not had any impact on the region’s vegetation.

Other indicators of human settlements were not found, such as ceramics, stone tools and terra preta or terra mulata (dark or brown earth)—distinctive Amazonian dark soils made by human activities, which often contain remains of artifacts, charcoal and other elements.

Piperno says that the study highlights the importance of integrated paleoecological, archaeological, anthropological, ecological and botanical research, to best understand the prehistoric legacies of Amazonia societies. She points out that the researchers intend to do more work in these remote tierra firme regions, which alone comprises more than 90 percent of the land area of the Amazon rainforest. It's a lot of territory yet to be explored in such depth, but essential to determining the overall reach of human impact on the land.

In addition to giving us a deeper understanding of how Amazon societies have coexisted with the rainforest, the study has further significance.

Put simply, Indigenous peoples play a key role in protecting these ecosystems. In the paper, the authors mention the collaborative relationship they established with some of the Indigenous communities in the region for conservation efforts, and highlight the importance of further studies of this kind and the inclusion of present Indigenous societies in the development of strong environmental policies.

“It is important to include modern indigenous peoples in conservation and sustainability efforts,” says Piperno.

“This study shows that Indigenous agricultural practices sustainably managed the forest's natural biodiversity for millennia,” says Sandweiss, a scholar of the effects of climate change on cultural development. “It draws renewed attention to Indigenous practice and urges planners to incorporate them to protect the Amazonian rainforest's natural biodiversity.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/foto_perfil_2020.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/foto_perfil_2020.jpg)