Remembering AIDS: The 30th Anniversary of the Epidemic

A collection of trading cards was an odd way to promote AIDS Awareness, but somehow, they worked

![]() To the mark the 30th anniversary of the HIV and AIDS epidemic, the National Museum of American History recently opened three displays throughout the museum that include a panel from the famous AIDS Memorial Quilt, a collection of public health and other political and scientific responses from the early 1980s, and a selection of brochures, photos and other archival ephemera documenting the difficult reactions and tragic stigmas associated with the disease.

To the mark the 30th anniversary of the HIV and AIDS epidemic, the National Museum of American History recently opened three displays throughout the museum that include a panel from the famous AIDS Memorial Quilt, a collection of public health and other political and scientific responses from the early 1980s, and a selection of brochures, photos and other archival ephemera documenting the difficult reactions and tragic stigmas associated with the disease.

Located near the first floor archives center, the two-case exhibit “Archiving the History of an Epidemic: HIV and AIDS, 1985 -2009" recalls the early years when so many Americans at first tried to ignore or dismiss the onslaught of the disease. On June 5, 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta reported that five young, gay men had died of diseases usually seen only in elderly or immune-depressed patients. Within weeks, many more cases surfaced. By 2007, more than 575,000 deaths would be attributed to the disease. Today, the illness has become chronic and manageable with the use of effective multi-drug treatments.

I knew I was in for an overwhelming story of tragedy, but then among a sea of brochures, photos and touching quotes, a handful of collectible trading cards caught my eye. The attractive illustrations featured prominent individuals who had been affected by the disease.

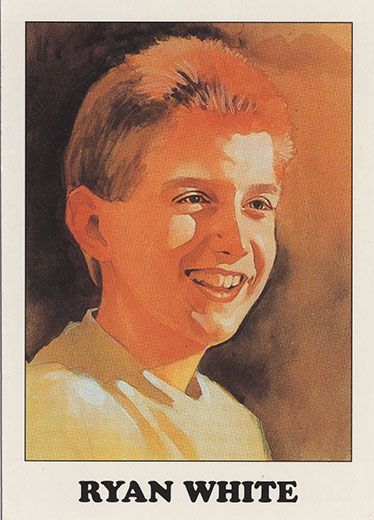

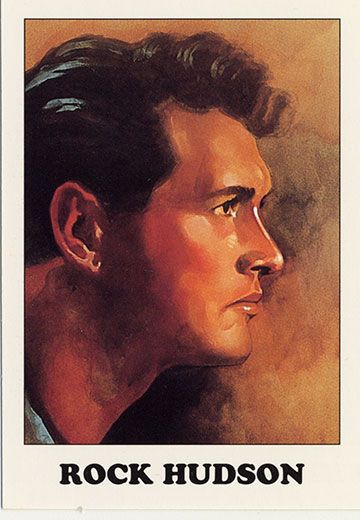

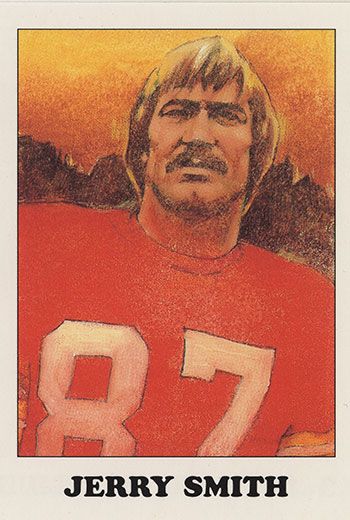

There was football player Jerry Smith, the first professional athlete to die of the disease; young Ryan White who contracted the illness through a blood transfusion; the handsome leading man Rock Hudson, who never publicly revealed his homosexuality.

“These individuals represent the broad spectrum of AIDS sufferers, Rock Hudson, the 1950s ideal of the American male (who happened to be gay and closeted) and Ryan White, a young hemophiliac, who contracted AIDS from a blood transfusion,” the show’s curator Franklin Robinson told me. “We see the terrible loss of talented individuals from all professions and individuals whose lives were cut short before they perhaps realized their potential. In a broad sense they represent that AIDS does not discriminate, young or old, gay or straight, whatever gender or race, anyone is capable of contracting AIDS.”

Called “AIDS Awareness Cards,” they were published in 1993 by Eclipse Enterprises of Forestville, California, and written by editor Catherine Yronwode. The illustrations were done by Charles Hiscock and Greg Loudon and the cards were distributed in sets of twelve, and packed with a condom to amplify the message of “safe sex,” a term that evolved along with the epidemic.

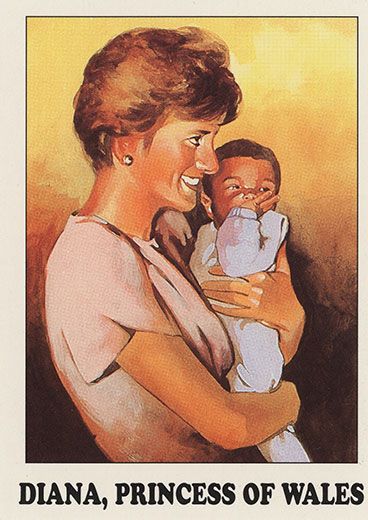

The cards included images of a young Princess Diana holding one of her children, as well as Elizabeth Taylor and Madonna.

“Through these women specifically,” says Franklin, “we see strong and prominent individuals who used their position and means within society to try and dispel the stigma of AIDS. Selflessly they took a stand of reaching out to the AIDS affected population with love and compassion when it was very unpopular. They illustrated that one can lead by example.”

When published the cards received negative publicity. Some accused Eclipse of capitalizing on the tragedy of the disease. But the editor Catherine Yronwode defended them. In a 1993 Orlando Sentinel article she said, “If you take the time to read the cards, you will come away with a good understanding of the disease.” While 15 percent of the generated revenues were donated to charitable groups fighting the disease, Eclipse ceased producing the cards in 1994, says Robinson.

In a time when people should have been interested in learning about AIDS and the mysteries that surrounded it and HIV, it was a struggle to grab the attention of the young adult audience, Robinson says when asked why he selected them for the exhibit.

“I thought the cards were a unique and innovative way for viewers to take away the message that AIDS is not just a disease affecting gay men but in a sense belongs to everyone. I hope the cards inspire viewers to reflect that someone they may know or admire is, or has been, affected by AIDS and that everyone may play a part in battling this epidemic.”

The 30th Anniversary of HIV and AIDS is a three-part commemoration and includes displays in the Archives Center and in the “Science in American Life” exhibit. A panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt is on view on the first floor in the Artifact Walls display cases.