Recognition of Major Osage Leader and Warrior Opens a New Window Into History

The story of Shonke Mon-thi^, a hidden figure in American history, is now recovered at the National Portrait Gallery

:focal(784x220:785x221)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/29/dd292ba7-34b9-45d1-bdc7-75a669fde2de/shonke-mon-thihorizontal.jpg)

In 1904, the priest of the Gentle Sky clan, Shonke Mon-thi^, came to Washington, D.C. as a member of an Osage delegation to negotiate the land and mineral rights of his nation. While in this city of diplomatic exchanges, the clan leader received an invitation from the Smithsonian Institution’s U.S. National Museum to pose for a photographer and have a plaster life mask made of his face.

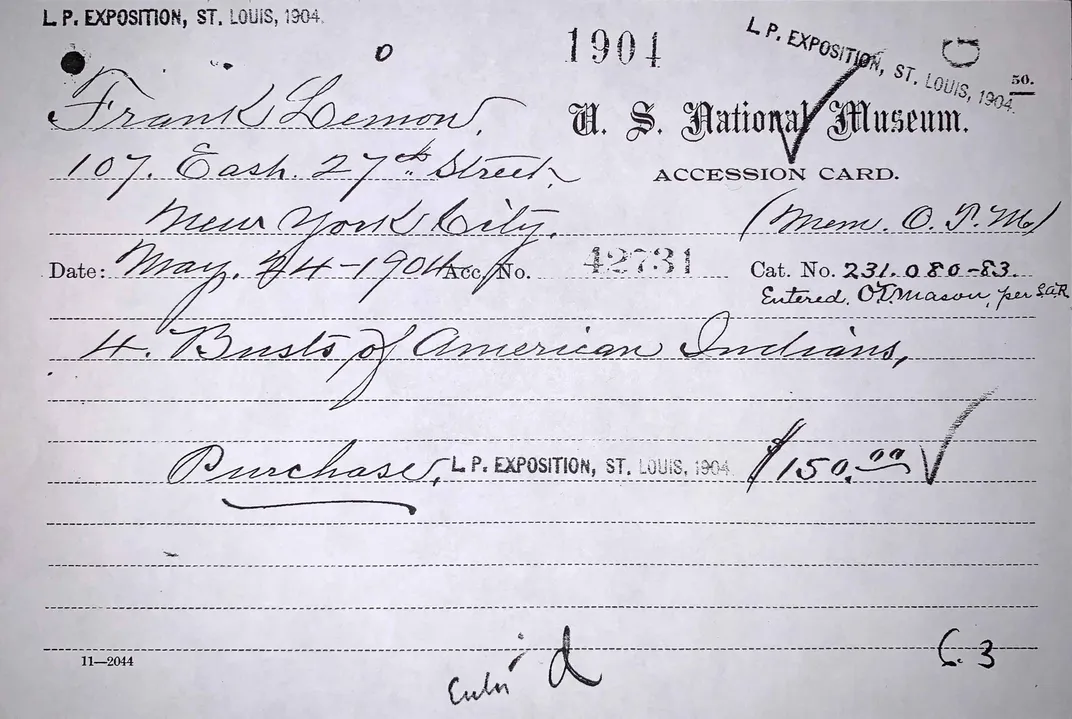

The resulting photographs and plaster were collected by the museum’s department of anthropology. They also served as the basis for sculptor Frank Lemon, who used them to craft a polychrome plaster bust that was exhibited at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. The fair’s extensive anthropological and ethnographic exhibits were widely varied, featuring busts, musical instruments, textiles, baskets, a model American Indian boarding school and numerous native villages with close to 3,000 indigenous people from North America and other parts of the world.

The St. Louis anthropological exhibitions, according to the U.S. National Museum’s annual report, were designed to illustrate the “higher culture of the Native American peoples as shown in their arts and industries.” The fair’s central topic of focus, however,—industrial and technological progress—created a symbolic contrast. Scholars Nancy J. Parezo and Don D. Fowler explore in depth the anthropologic exhibitions of the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition and the ideas on race that it promulgated. According to their book Anthropology Goes to the Fair: The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, the displays helped to foster a divide between the natives as representatives of so-called “primitive” societies, and the fair’s urban, middle and upper class, Euro-American audiences, as emblematic of “civilized” Americans.

In 2014, Latino artist Ken Gonzales-Day, while studying on a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, was exploring the anthropology collections at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and came across Lemon’s 116-year-old sculpture of Shonke Mon-thi^.

Gonzales-Day’s research and the recent acquisition of one of the artist’s photographs into the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery represents a new approach to bringing acknowledgment and honor to one of the most decorated of Osage warriors and helps the museum to present a more inclusive view of American history. The story of how it happened and the process involved is a fascinating one.

The Story of Shonke Mon-thi^

“When I first saw Shonke Mon-thi^ ’s bust,” says Gonzales-Day, “I felt certain he was a man of importance. He had been painted with great care and unlike some other works in the collection, his name appeared on the plinth.” The polychrome bust depicts an elder man with a stern expression; his hair is shaved on the sides while locks fall to his neck. The sculpture is chipped at various places, the white plaster breaking through the subject’s brown skin evokes the age of the object itself.

“I thought perhaps it was part of a group of works I had been searching for, that had been displayed as part of the Louisiana Purchase International Exposition,” says Gonzales-Day. “It was. So not only was he a man of importance to his people, his likeness was also presented to exposition goers, and as such, he clearly represented a missing piece from the history of racial formation in the United States.”

For more than a decade, Gonzales-Day has traveled to museums around the world to photograph both art and ethnographical objects as part of his project Profiled (2008–present), examining and studying the sometimes subtle and sometimes blatant racial biases in the sculptural representation of white bodies and bodies of color. His search has taken him to such renowned collections as L’École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Bode Museum in Berlin, Tokyo National Museum, Museo de Nacional de Arte de Mexico City, and The J. Paul Getty Museum.

During his 2014 fellowship, the artist had dedicated much of his time to researching and photographing sculptures of Native Americans in several Smithsonian museum collections. “I wanted to explore how Native Americans were represented in our national museums. I was searching for forgotten histories and I continue to believe that uncovering and photographing historically forgotten works can allow us to see the past in new ways. My artistic approach borrows from restorative justice practices where punishment is replaced with reconciliation and restitution to create works that promote dialog, recover history and contribute to the public discourse on the history of racial formation.”

Historic portrait sculptures of Native Americans, he concluded, are rare at the National Portrait Gallery. Native individuals, Gonzales-Day noted, are mainly portrayed in lithographs and engravings made by European and Anglo-American artists since the 17th century and printed for wide dissemination, but seldomly are they portrayed in the medium of sculpture, which is often associated with social prominence and historic permanence.

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the artist also noted that many sculptural depictions of Native Americans within that museum’s collection are allegorical. But Gonzales-Day found that the largest number of sculptures representing specific Native American individuals are housed in the Natural History Museum’s collection. These artifacts frequently take the form of life masks, heads and busts made out of plaster, many of which were collected by the Smithsonian’s first anthropologists and ethnologists at the turn of the 20th century.

Originally created to illustrate the different human “types,” these sculptures served as tools to depict racial differences based on the physical anthropology research methodologies of the day—which have since been debunked by anthropologists arguing for an understanding of the social constructions of race. As manifestations of this earlier history of the study of race as a biological category, however, these objects still have powerful impact on our thinking today.

Gonzales-Day’s photographs of many of these sculptures were accompanied by an effort to resurface the details of the lives of these individuals. He pored over collections files, census records and archives in an effort to piece together their life-stories. The artist came to recognize that these sculptures were part of the Smithsonian’s institutional history and that in a sense, their presence at the Natural History Museum was a counterbalance to their absence at the Portrait Gallery.

I joined the artist in his effort to research the individuals they represented. The process was challenging, especially given the fact that many indigenous names at the turn of the 20th century had no standardized spellings. The base of the bust identifies the man as Shoñ-ke-mã-lo, but alternate spellings also included Shunkahmolah or Shon-ge-mon-in. Thus, we learned that sometimes switching an “o” for a “u” or adding a hyphen between syllables could yield information that might otherwise have remained hidden.

Under the guidance of the Natural History Museum’s curator of North American ethnology Gwyneira Isaac and research collaborator Larry Taylor, I contacted the Tribal Historic Preservation Offices and the tribal museums of each community represented in Gonzales-Day’s photographs. During my conversations, I provided respondents with information about the artist’s project, shared images of relevant works, and invited individuals to help piece together the stories of the sitters from their communities.

Following the museum’s protocol for these collaborations, I also tried to locate the living descendants of the individuals. Our contact with the Nations yielded meaningful exchanges that pointed to how contemporary readings of these anthropological busts, accompanied by conversations with communities and descendants, can help address historical trauma and erasure, and bring overdue recognition to forgotten figures.

The process of conversations with Native communities, including the Osage, Pawnee, Seneca, Lakota Sioux and the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, culminated with an exhibition in 2018-2019 that showed Gonzales-Day’s work along with the revealing works of the artist Titus Kaphar.

A case in point was the outcome of our research around the portrait of Shonke Mon-thi^. After months of looking for clues by cross-referencing sources with different spellings, we finally understood the stature of the sitter in his community and his contributions to the United States.

Shonke Mon-thi^ is often referred to as Shunkahmolah, his birth date is unknown, his death date is believed to be around 1919. He was a spiritual and political leader of the Osage Nation and won honors during an attack on Confederate forces in 1863. By the time of his death, Shonke Mon-thi^ was one of three living men who had earned all 13 o-don, or war honors, given unanimously by his nation. In addition, he assisted Smithsonian anthropologist Francis La Flesche, a member of the Omaha Tribe, in documenting Osage religious rites. The details of the subject’s life, including his participation in the Osage delegation to Washington, D.C., in 1904, made clear his historical significance. The Portrait Gallery’s curatorial committee agreed with this conclusion, so I reached out to representatives of the Osage Nation and asked if they would support the Portrait Gallery’s acquisition of Gonzales-Day’s related photograph.

I subsequently made contact with Steven Pratt, great grandson of Shunkahmolah, who received the idea enthusiastically and provided additional details on the biography of his great grandfather. I learned that Shonke Mon-thi^ (“Walking Dog”) earned his name for his remarkable ability to run long distances carrying messages between Osage chiefs. Anglo-Americans, unable to pronounce his name, had started calling him Shunkamolah.

Pratt supported the acquisition but asked that the title of the sculpture be changed to his great grandfather’s original name. With the approval of the Osage and the Traditional Cultural Advisors Committee, as well as that of the National Portrait Gallery’s Board of Commissioners, Gonzales-Day’s photograph of the Portrait of Shonke Mon-thi^ entered the museum’s collections this past summer. To complete the circle, Gonzales-Day gifted a print of the photograph to Steven Pratt, as a gesture of respect for the living legacy of his ancestor.

Once the process of acquisition had ended, I could not help but marvel at the remarkable turn of events this acquisition embodied. A major political and spiritual Osage leader and warrior had claimed his rightful place in the nation’s Portrait Gallery.

Thanks to the vision of one contemporary artist, who through his camera lens reframed an anthropological bust as a memorializing portrait, and after the constructive dialogue between Native stakeholders and museum professionals, Shonke Mon-thi^’s visual biography now resides in a national collection dedicated to the individuals who have shaped America’s history and culture.

I would like to thank Gwyneira Isaac, curator of North American Ethnology at the National Museum of Natural History, for her valuable insight into the history of anthropological busts, casts and the development of theories on race. Thanks as well to Larry Taylor, a pivotal figure in the rediscovery of Native American face casts in museum collections, for sharing his knowledge of Shonke Mon-thi^ and the sculptures known as the "Osage Ten." Finally, my deep gratitude goes to Steven Pratt, the great grandson of Shonke Mon-thi^, Andrea Hunter, director of the Osage Tribal Historic Preservation Office, and the Traditional Cultural Advisors, for their counsel and trust in the process of representing Shonke Mon-thi^ at the National Portrait Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/staff_tainac.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/staff_tainac.jpg)