In Obama’s Official Portrait the Flowers Are Cultivated From the Past

Kehinde Wiley’s painting is full of historical art references says Kim Sajet, the director of the National Portrait Gallery

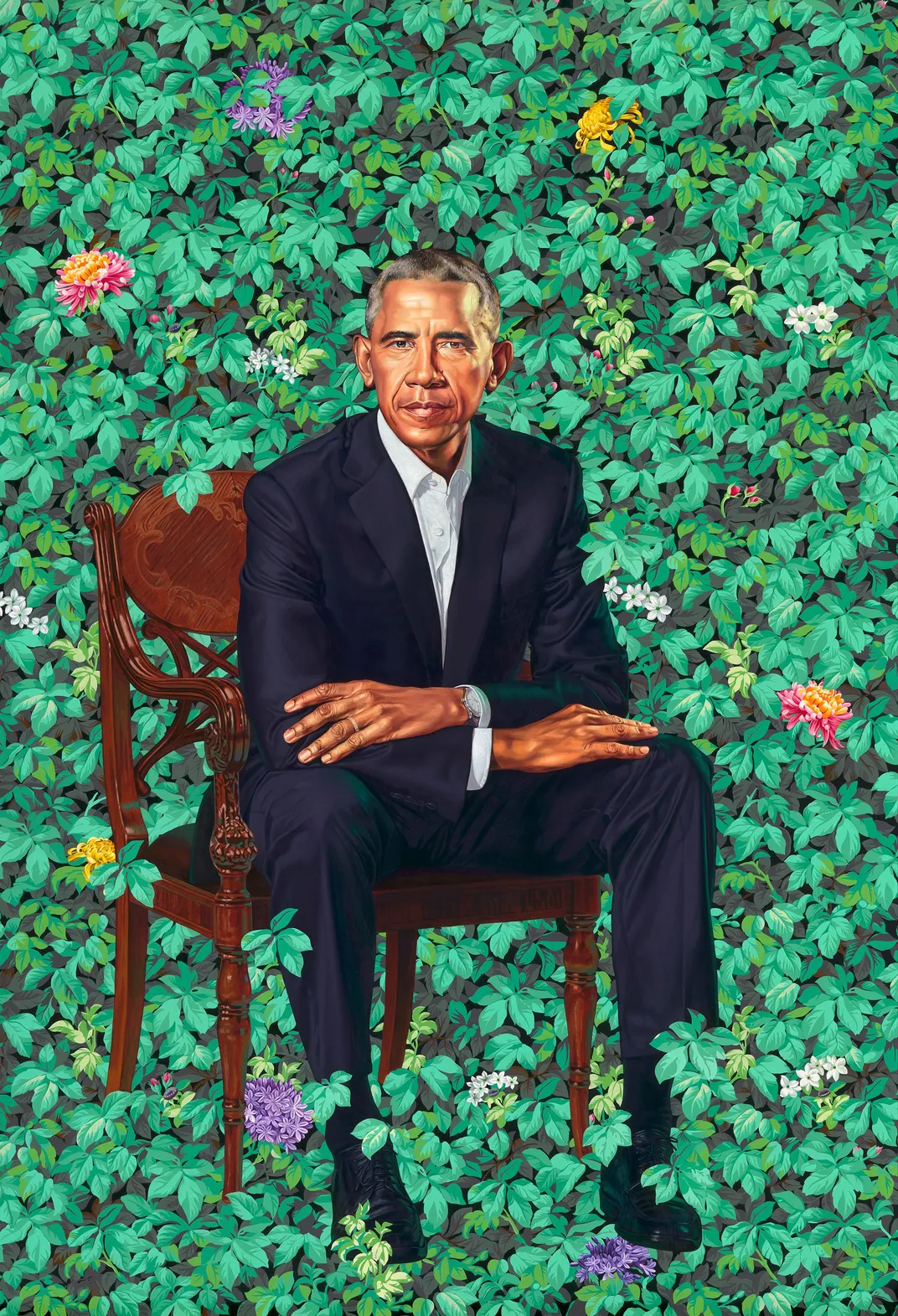

In the double-duty world of semiotics, or the reading of signs, the language of flowers has for centuries been used to carry coded meanings in visual art. As the official portrait of President Barack Obama by Kehinde Wiley attests, there is so much more than meets the eye.

Seated in a garden of what looks to be wild roses, the 44th president of the United States is surrounded by botanical symbolism meant to tell the life and history of the nation’s first African-American president.

The purple African lily symbolizes his father's Kenyan heritage; the white jasmine represents his Hawaiian birthplace and time spent in Indonesia; the multicolored chrysanthemum signifies Chicago, the city where Obama grew up and eventually became a state senator.

Each flower relates to a portion of Obama's life. Together the lily, jasmine and chrysanthemum—combined with rose buds, the universal symbol for love and courage—provide a metaphor for a well-cultivated, albeit sometimes tangled life full of obstacles and challenges.

Mention of a garden paradise can be found in writings as far back as 4000 B.C. during the Sumarian period of Mesopotamia where desert communities highly valued water and lush vegetation. The word 'paradise' comes from the ancient Persian word pairidaeza and there are more than 120 references to gardens in the Qur’an. In woven rugs, wall decorations and illuminated manuscripts from the 13th century onwards, the tree of life is a frequent symbol of understanding and truth, surrounded by intricate arabesque patterns of geometric flowers to symbolize the eternal and transcendent nature of God.

Flower symbolism appears on Chinese pottery dating to the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 220 A.D.) and both the rose and chrysanthemum were originally herbs that the Chinese cultivated and refined over thousands of years. Associated with longevity because of its medicinal properties, people drank chrysanthemum wine on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month as part of the autumn harvest.

Around 400 A.D., Buddhist monks brought the chrysanthemum to Japan where it became the official seal of the emperor. By 1753 Karl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, coined its Western name from the Greek words “chrysos” meaning gold, and “anthemon” meaning flower after seeing a poor specimen from China in the herbarium of fellow naturalist and world traveler Joseph Banks. Exactly a century later, when the U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry entered the Bay of Tokyo in 1853 and forcefully opened Japanese trade to the rest of the world, the exotic associations of the chrysanthemum transferred its meaning to Western decorative arts.

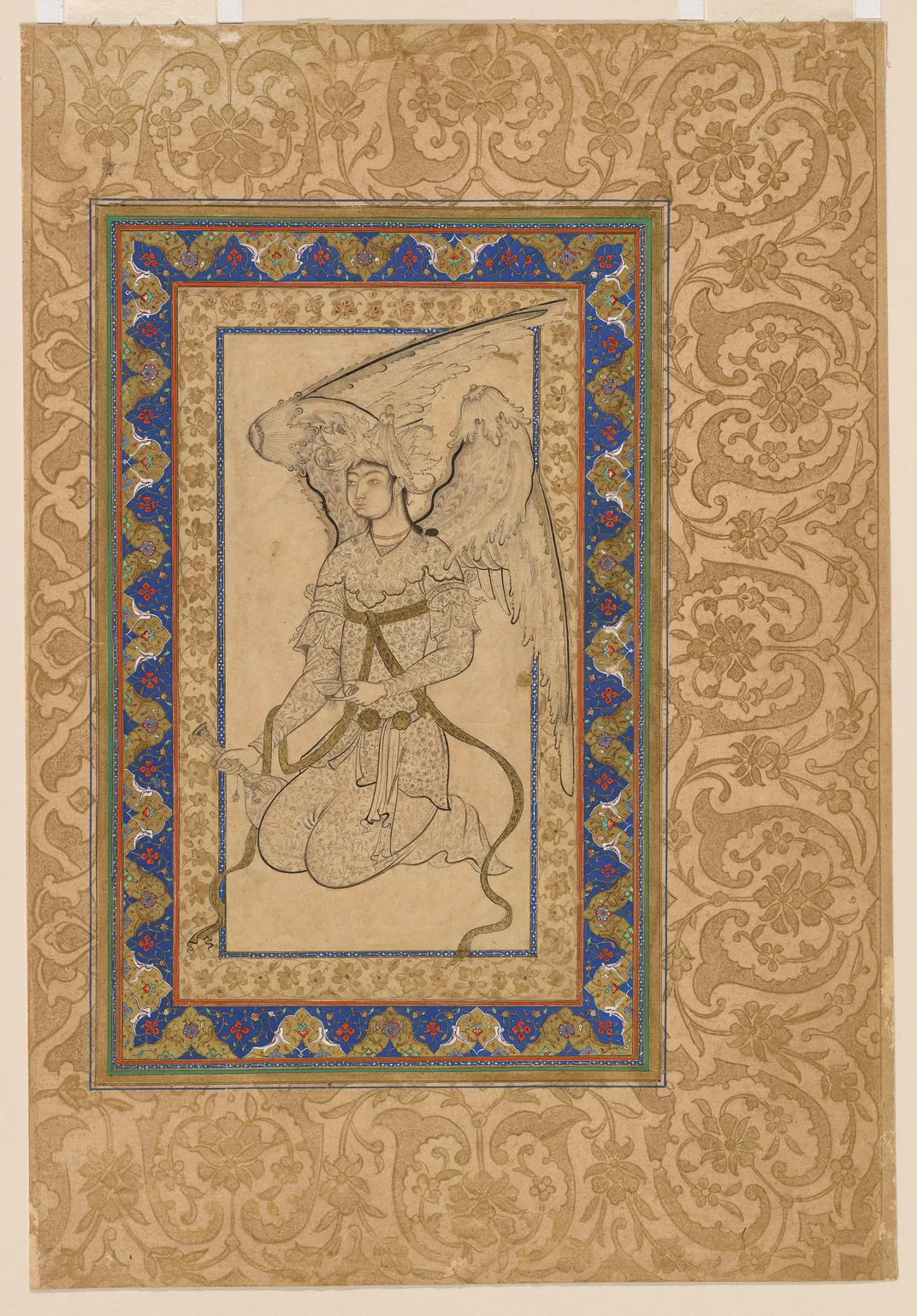

When the Mongols invaded western Asia and established a court in Iran in the mid 13th-century floral symbols common in Chinese art such as the lotus symbolizing purity, the peony connoting wealth and honor, and the Chinese monthly rose, jueji, famous for blooming throughout the year and known for youthful beauty and longevity, began appearing in Islamic designs albeit in more stylized form.

The twisting serrated leaf known as the 'saz' displayed these symbolic flowers by use of intricate patterns that unified the composition. The kneeling angel attributed to the painter Shah Quli in the collections of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, the Smithsonian's Museums of Asian Art, for example, shows pomegranate flowers to indicate fertility set within a saz leaf border.

Kehinde Wiley's floral associations date predominantly to Western traditions going back to 15th-century medieval Europe, where botanical references were deliberately placed in everything from stained glass windows, illuminated manuscripts, liturgical garments, church decoration and paintings to expand simple biblical stories into more complicated teachings of the church. Developed in an age when most worshippers couldn’t read Latin, flowers provided a bridge between the ecclesiastical world and that of the everyday.

Flowers arranged in the foliate bar boarder of an illuminated manuscript in the Getty Museum collections and made by the Master of Dresden around 1480-85, for example, show a veritable florist-shop of symbolism around a scene of the crucifixion with red roses marking the shedding of Christ's blood, dianthus (early carnations) the carrying of the cross, irises the resurrection, white lilies for purity and chastity, the three-petal violet for the holy trinity of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, and columbines to represent the Virgin Mary's sorrow, together with strawberries, her "kind deeds.

Many of these flowers were in fact herbs used for medicinal purposes and thus the herbarium of medieval times were not just well known, but based on direct observations of nature.

The love of flower symbolism continued into the Victorian era and is especially wonderful in relation to William Morris and the pre-Raphaelites who were inspired by the theories of John Ruskin to turn to nature for inspiration and soothe harried workers of the Industrial Age. A Sweet Briar wall paper designed by Morris in 1917 was intended to bring the garden into the home, while a tapestry panel of Pomona the goddess of fruit and trees by Edward Burne-Jones for Morris's company surrounds herself with the fruits of nature and the symbolic blessings of women (apple and Eve) and fertility (oranges), surrounded by many of the botanical symbols of the European Renaissance listed above.

Kehinde Wiley's portraits are distinctive because of the colorful and highly intricate all-over patterns he employs to foreground his subjects, such as LL Cool J, also on view at the National Portrait Gallery.

The treatment in President Obama's portrait, however, is subtly different. Instead of an obviously manmade decoration where nature is reduced to ornamentation, the vegetation around the president has not been 'tamed.' As Wiley in his remarks at the unveiling acknowledged, "There is a fight going on between he in the foreground, and the plants that are trying to announce themselves at his feet. Who gets to be the star of the show?"

The nature around President Obama is living, not static; green with heights of floral color, not the reverse; and the garden that has grown up about him provides both a metaphorical past of covered ground with a future of still-budding potential.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/16/6316c5fd-d52a-436d-877e-f88f7dd498db/kw_rosebud.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KSajet_portrait_orange_1.13.JPG)