A New Photo Exhibition Depicts Just How Dramatic Mother Earth Can Be

Iceland, the land of fire and ice, brings vivid focus to the raw power of a geophysically active Earth

For more than 50 years, photographer, documentary film maker and naturalist Feo Pitcairn has traveled the world in search of subjects for his work. From the plains of Africa to the coral reefs of Indonesia and the islands of the Galapagos, he’s seen the tremendous diversity nature has to offer. So when he says a place is more diverse than any he’s ever seen before, that’s saying something.

“On my first tour of Iceland in 2011, I was immediately captivated by the stunning landscapes—craggy ocean shorelines, volcanic mountains, hot springs, ice fields and so much more,” he says. “What struck me about Iceland predominantly was the amazing diversity of nature and the forces of nature at work.”

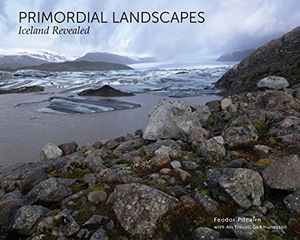

His photographs are the feature of the new exhibition Primordial Landscapes; Iceland Revealed at the National Museum of Natural History. Coinciding with the United States’ two-year term as chair of the Arctic Council, the international forum that coordinates Arctic policy, the show is a collection of photographs, poetry, audio and lighting effects, and a few select objects from the museum’s collection.

Iceland is one of the youngest land masses in the world—having bubbled up from beneath the Atlantic Ocean where North American and European tectonic plates are spreading apart. Primordial Landscapes pays homage to a land that is still being built—transformed by fiery volcanic eruptions, the flow of glacial ice and melt water, and carved out by wind and waves.

Forty-one of Pitcairn’s large-format photographs are arranged to portray those three themes: fire, ice, and transformation. Together, they reveal an earth alive in its brutality and magnificence. Benjamin Andrews, the museum's curator of mineral sciences, says the images convey the essence of the earth as a planet that continually resurfaces itself. “It’s wonderful to have an exhibit where Earth is the star,” he says. “These images show processes that have been happening on Earth for billions of years.”

Pitcairn made eight trips to Iceland to capture the diversity of the country which is about the size of Kentucky. “With each return to this place at the edge of the Arctic Circle, I became more intimately humbled by nature’s power,” says Pitcairn. With an exquisite eye for lighting and composition, Pitcairn has captured the sweeping landscapes in vibrant detail.

His images reveal deep molten red fountains of lava reaching from fissures in the black volcanic earth, fields of glacial ice permeated by a maze of crevasses, and vivid green moss covered terrain carved by foaming waterfalls.

The large-format digital Hasselblad he used exclusively on the project captures 60 million pixels, allowing for a spectrum of colors that far exceeds what’s possible with film or smaller format digital cameras. “I see myself as a fine arts photographer in my new career” says Pitcairn, an octogenarian with a long career as an award winning underwater cinematographer and wildlife photographer. “I’m now coming from a different perspective where it’s much more about trying to capture something that’s deeply evocative, that resonates with the human spirit.”

In reflecting that goal, the exhibition itself incorporates elements meant to evoke a broader sensory response to Iceland’s stark, compelling landscapes. Throughout the gallery, excerpts of poetry written by renowned Icelandic geophysicist, author, poet and former presidential candidate Ari Trausti Guðmundsson are projected on the walls above the photographs, accompanied on one wall by the projection of a simulated aurora borealis. The sounds of Iceland are also incorporated into the exhibition. Birds, bubbling geysers, rumbling volcanoes, ocean waves, wind, groaning glaciers and Guðmundsson reciting his poetry resonates from one end of the exhibition.

Exhibit developer and project manager Jill Johnson says the goal was for Primordial Landscapes to be more than a photo exhibit. “For us, having poetry is really different,” she says. “The intention was for it to be more of an affective experience, to transport people to Iceland. I think the poetry helps get people inspired by these landscapes, and hopefully they can feel the passion that comes from his expression.”

That’s why they chose to have him recite the poems in Icelandic, although he wrote them originally in English for an English-speaking audience.

“When you are writing poetry about Iceland for foreigners you do it differently than if you were doing it for the Icelanders themselves,” He says. “I feel that I have to explain or evoke feelings that sort of get a message across. That you have to preserve as much as you can of the ambiance, of the character of Iceland for the world to experience, not just us [Icelanders].”

As a country teeming with the scars and still-open wounds of a geophysically active world, one that by its mere existence celebrates the raw power of a changing earth, Iceland’s character comes through in this exhibit.

But as a discourse on life at the edge of the Arctic Circle, the issue of climate change and human impact is broached only briefly through references to melting glaciers in a few of the photo captions, but the near omission seems, if not intentional, at least, natural.

“I was not on a mission to knock people on the head about that,” says Pitcairn, “What I think about Iceland is that it’s one of those places where nature rules, and there’s not that many places like that around the world. When you come to Iceland you so much feel that nature is the dominant influence.”

In some ways, the absence of climate change speaks louder than if it had been confronted head on. Primordial Landscapes does not portray a fragile, threatened earth. Rather, as the title suggests, it presents Earth stripped of the human timescale, a terrain beneath our feet that is beyond human influence. One sequence of photos depicts the largest known lava flow on the planet, known as Laki. The flow was laid down in 1783, the same year the Americans celebrated the end of the revolutionary war. Yet in another aerial shot of the island of Surtsey is an amoebic mound of windblown peaks, black earthy shorelines and mossy green meadows. It was built by volcanic eruption in a matter of weeks just 50 years ago.

That is not to say that human presence is completely absent from this exhibit; however, the collection of photos seems to put us in the context of a bigger picture. The signs of humanity are portrayed in the past tense as a seemingly natural part of the landscape. There is an image of an abandoned farmhouse blending far off in the distance into a wheat-colored field at the base of a mountain. Another shows a cairn of grey stones set in an expanse of grey rubbly terrain. The façade of an old wooden cottage built of grey wood and grey stone into a grey hillside as if it grew there along with the moss that covers it.

Guðmundsson’s writings reflect a similar humbling at the hands of nature’s forces. “In my poetry I’m trying to get this message across that in very few cases do we really influence the earth,” Guðmundsson says. “We may change the landscape somewhat, we may pump greenhouse gases into the air, but in the end it’s always the earth that has the upper hand. Knowing that, you have to behave differently. You have to behave with some modesty. You have to live off nature without harming nature.”

Icelanders have become especially attuned to their impact on their land in recent years, not only because of climate change and melting glaciers, but also because of potential increases in shipping traffic as sea ice melts and, most urgently, the rapid expansion in tourism. The population of just 323,000 is now welcoming more than one million visitors a year.

“If this continues we will be faced with this tricky question of how many tourists can we accommodate without spoiling what the tourists are after?” Guðmundsson says. “We have to solve this problem somehow quite soon.”

But these are matters for another venue. Primordial Landscapes is perhaps one place to open the discussion. As part of the Museum of Natural History’s plan to celebrate the Arctic over the next two years, the exhibit will serve as a focal point for public programming and educational activities.

Primordial Landscapes: Iceland Revealed is on view in the Special Exhibitions Hall on the first floor of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., through April 2017.

Primordial Landscapes: Iceland Revealed

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/1f/ed1fa515-0cbb-40c5-a118-192dd351da67/primordiallandscapesplate6hiresweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/76/7c76158c-0c38-4e61-a91e-54531a706d75/primordiallandscapesplate24hiresweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/21/d621779b-bcc7-4c39-9b41-e50b22676ce1/primordiallandscapesplate27hiresweb.jpg)