Museum Curators Reflect on the Legacy of the Queen of Soul

Aretha Franklin dies at 76; her memory lives on at the Smithsonian in artwork, photographs and other ephemera

Aretha Franklin was no one’s understudy. But when the Queen of Soul took the stage at the 1998 Grammy Awards, she was not the singer audiences expected. At the eleventh hour, operatic legend Luciano Pavarotti had called to cancel his long-awaited headliner performance of “Nessun dorma” (None Shall Sleep) due to illness—and with no warning or preparation, Franklin agreed to step in.

It was neither her genre nor her typical vocal range. But Pavarotti was Franklin’s dear friend, and she had performed a heartfelt tribute to him earlier that week. With only 20 minutes notice, Grammy producers burst into Franklin’s dressing room with an outrageous request—and moments later, they were anxiously ushering her on stage.

They needn't have worried. That night, the lady legend of soul was luminous.

In an honorific tenor, Franklin delivered one of the most memorable performances of her career, obliterating the implicit boundaries that had fenced in one of opera’s best-known arias. Franklin’s tribute was not entirely faithful: No one would have mistaken her voice for that of a white, male Italian (as per the song’s tradition). But she had never intended it to be.

“I was mesmerized,” recalls Dwandalyn Reece, curator of music and performing arts at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, who was in the audience that night. “She brought her own signature style and interpretation. She translated [“Nessun dorma”] and really captured the essence and emotionalism of the piece.”

At the 1998 Grammy Awards, Franklin wasn’t a replacement. She was a visionary.

Aretha Franklin died on August 16 at age 76, surrounded by friends and family at her home in Detroit, Michigan. The much-beloved Queen of Soul leaves behind a stunning legacy that revolutionized the genre of rhythm and blues, and empowered generations of civil rights activists and feminists. At the Smithsonian Institution, her life’s story is remembered in photographs, artwork, recordings and other ephemera.

“She transformed popular music,” says Reece. “She [carried on] the traditions of African and African-American music, bringing the sacred and secular together. . . and [transcended] everything from historical movements to base emotions.”

Franklin features in the African American History Museum’s Musical Crossroads exhibition, curated by Reece to reflect the prominent influence of African-American music on American culture.

“You hear her in every singer who sings in popular music, even today,” explains Reece. “Her sense of liberation has opened the floodgates of singers who follow her, and she carries on the tradition of singers who preceded her as well. She’s a cultural linchpin.”

Franklin was born in Memphis, Tennessee, on March 25, 1942, but spent most of her childhood in Detroit, where she moved at the age of four. It was here, in the Baptist church where her father was minister, that her musical career officially began.

Her vivid, commanding voice, honed by Sunday gospel and the burgeoning jazz-fevered culture of Detroit, quickly exceeded the spaces it was granted in a church pulpit. Before long, she had mastered the piano and was belting out show-stopping solos with ease. Franklin’s talent was clearest of all to her father, who became one of her first managers during her teenage years.

After moving to New York at the age of 18, Franklin consciously transitioned into secular music. Reflecting on the strained racial tensions that had pervaded the segregated neighborhoods of her childhood in 1950s Detroit, she began to test the waters of signing R&B, noting in a column in the Amsterdam News, “the blues is a music born out of the slavery day sufferings of my people.”

At the same time, a good friend of her father’s named Martin Luther King, Jr., was making waves across the nation. As Franklin’s voice began to reverberate across the musical world, it sent echoes through a rising historical movement. In 1967, Aretha’s reclaimed feminist anthem cover of Otis Redding’s “Respect” topped the charts. A year later, King was assassinated; Franklin eulogized him with a heartfelt rendition of Thomas Dorsey’s “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.”

“She really [blurred] those boundaries that divide black and white music, or sacred and secular music, or what musical sounds and techniques can really describe and define what a musician should be,” says Reece.

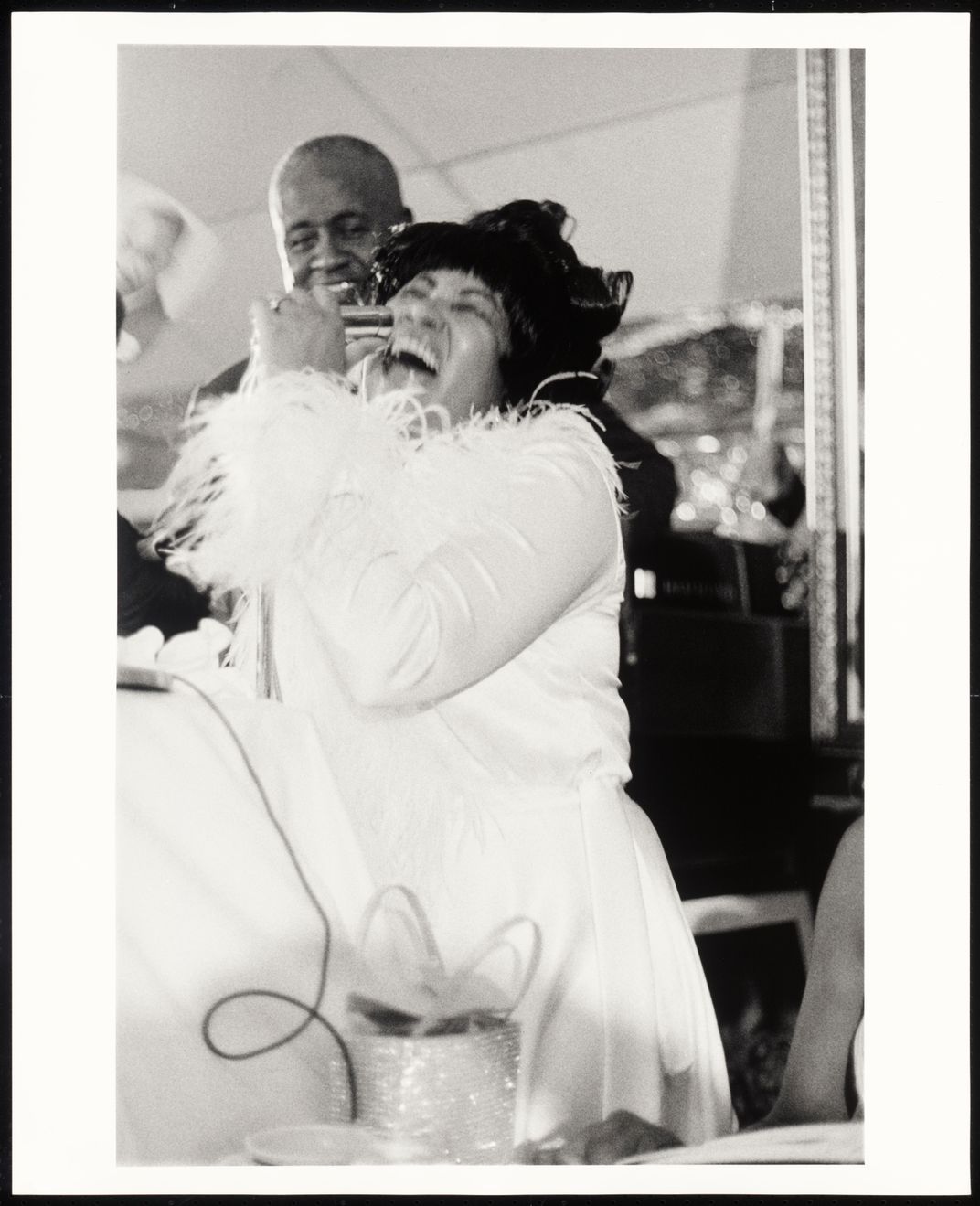

By the end of the 1960s, Aretha Franklin had been dubbed “The Queen of Soul.” She was an unmistakable juggernaut of musical accomplishment: Her voice, strong and defiant, boasted a colossal range to match her spirit. One particular famous photo, currently on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, depicts Franklin decked out in a white, feather-cuffed jacket as she croons ebulliently into a microphone at the 1968 Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“She brought innate, keen sense of musicianship and style and really defined soul as an essence,” Reece explains.

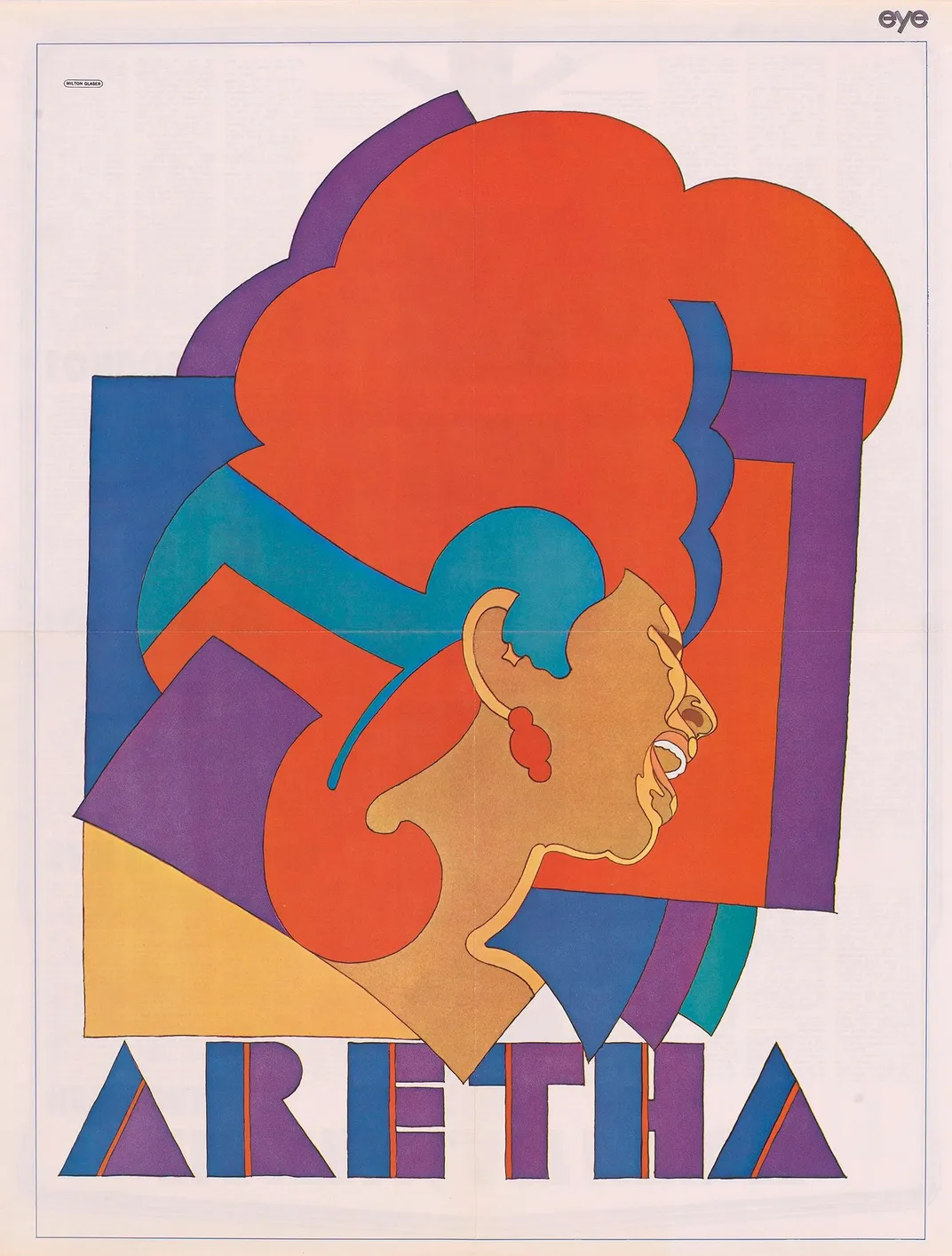

In November of that same year, a poster of Franklin appeared as the insert in the short-lived Eye Magazine, a Hearst Corporation-sponsored publication for young adults. Rendered by famous graphic designer Milton Glaser (who is also responsible for the “I love NY” logo), the poster features a “highly emotional” view of Franklin, mouth open, sporting a “glorious” 1960s bouffant hairdo in vibrant reds, blues and purples, says Asma Naeem, the National Portrait Gallery’s associate curator of prints, drawings and media arts.

“[The portrait] has an electricity, a pulsating rhythm, that you can just imagine that her voice had,” says Naeem. “Glaser’s design—from the patterning, color, composition and shapes, all suggest the amazing verve and energy of Aretha Franklin.”

Though Eye Magazine went out of print in 1969 after distributing only 15 issues, this poster would go on to sell millions around the world. An original of the poster, complete with a set of cautious instructions for its removal (“tear carefully along the perforated line”), was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2011. Its caption honors the “First Lady of Soul,” whose songs were “earthy and sensual, with the pulsing rhythm of her early gospel days.”

“It’s an important historical document,” says Naeem of the poster. “It really captures the mood of the period, the aesthetic of the era. . . it shows not just the incredible relevance and majesty of Aretha Franklin, at a very early point in her career, but also the incredible energy of soul music [that] has been a part of our culture for so long.”

At the same time, the poster’s unassuming roots speak to the ubiquity of the woman it depicts. Franklin’s 25-by-25-inch portrait, originally intended for the preteen target audience of an oft-forgotten 1960s periodical, hangs alongside gargantuan life-sized portraits and fragile oils on canvas—but is perhaps even more compelling in its unpretentious accessibility.

“Portraiture is around us in the most unsuspecting of ways,” affirms Naeem.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/54/4e548f72-4b6a-4d01-88ac-b7ecd2e7dec8/aretha_franklin_courtesy_of_the_national_portrait_gallery.jpg)

Three years ago, Franklin was among the recipients of the 2015 Portrait of a Nation Prize at the National Portrait Gallery’s inaugural American Portrait Gala.

“The Prize celebrates individuals in their accomplishments in their various fields,” Naeem explains. “We decided to honor individuals whose portraits are already in the [Gallery’s] collection for their exemplary achievements.”

All five 2015 honorees—Major League Baseball Hall of Famer Henry “Hank” Aaron, U.S. Marine and Medal of Honor recipient Corporal Kyle Carpenter, fashion designer Carolina Herrera, designer and artist Maya Lin and Franklin—received their prizes in person. At the Gala, Franklin performed “Respect,” “Freedom” and “Chain of Fools” in the Gallery’s Kogod Courtyard, rousing “the gowns and tuxes out of their chairs,” according to the Washington Post. Before the close of the evening, she posed for a photo next to her own poster, a likeness from nearly 50 years prior.

In her 1968 depiction, Franklin was only 26 years old—but her legacy had already been firmly established. In the decades following, Franklin would go on to collect 18 Grammys—as well as both a Grammy Legend Award and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award—and become the first woman to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Her voice was eventually declared a “natural resource” of Michigan. In 2005, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom—and ten years later, her performance of “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” at the 2015 Kennedy Center Honors moved President Barack Obama to tears.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History boasts more than 100 of Franklin’s records in its collection, chronicling the “vast expanse and depth of her recording career,” says John Troutman, the museum’s curator of American music. “[She had such a] breadth in her songwriting and vocal prowess. . . [and even] crafted incredibly intimate scenes of daily life,” Troutman reflects. “One of my favorite and often-overlooked of her songs is ‘First Snow in Kokomo’ [from the 1972 album Young, Gifted and Black]. . . the song is absolutely breathtaking in its quiet celebration of the profound grace, awe and joy of life.”

In her last years, Franklin’s health faltered noticeably. In 2010, she began to cancel performances due to her ailments. She requested privacy, rarely speaking of her illnesses.

However, Franklin determinedly continued to book concerts across the country until February 2017, when she officially announced her impending retirement. Her last show occurred in November of 2017.

Early on Monday, August 13, family members reported that Franklin had been hospitalized and was “gravely ill.” She returned home later that same day. Publicists confirmed her death the morning of August 16.

“Her image as a legend and a pioneer looms very large,” says Reece. “It’s hard to imagine a world without Aretha Franklin.”

The National Portrait Gallery honors the life of Aretha Franklin with an In Memoriam display of the 1968 poster created by graphic designer Milton Glaser. The poster will be on view August 17 through August 22, 2018.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/32/4a32f0d9-b33d-45a6-824d-408e5a863445/aretha_franklin_with_her_portrait_courtesy_of_angela_pham_bfacom.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/c7/54c72839-885f-40e6-bb3d-b06eb7651178/2-aretha_franklin_performs_at_the_american_portrait_gala_courtesy_of_angela_pham_bfacom.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/ab/48abed00-97bc-4187-bfcb-c78fd4e2f50c/aretha_franklin_courtesy_of_angela_pham_bfacom.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)