The Latest on the Kickstarter Campaign to Conserve Neil Armstrong’s Spacesuit

As a new biopic blasts off, the protective suit worn by the ‘First Man’ on the moon is readied for its star turn

:focal(400x358:401x359)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/a2/41a2be6a-f22e-4753-8d20-6447b88d9ecc/oct018_a01_prologue-copy_webcrop.jpg)

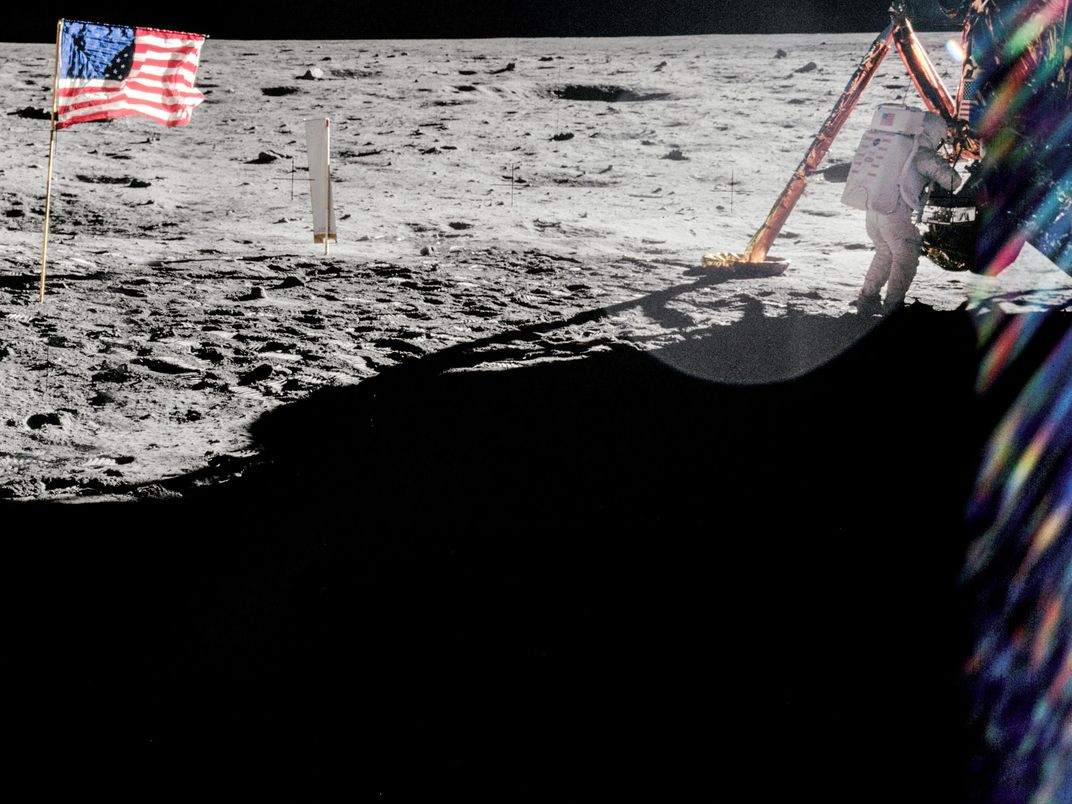

On the 49th anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s historic moonwalk—the transfixing “one small step...one giant leap” moment—his spacesuit, lunar dust still embedded in it, lay facedown on a table, its booted feet dangling off the edge, pointed toward the earth.

A recreated version of the suit makes a center-stage appearance in October, as First Man—the biopic reprising the heroism of Armstrong and his fellow Apollo astronauts, starring Ryan Gosling as Armstrong and Claire Foy as his wife, Janet—opens in theaters. According to costume designer Mary Zophres, she and her team consulted NASA and Apollo engineers—and located original space-age materials and fabrics—in order to replicate the suits. "We put in a herculean effort to make it as real as possible."

Upon its triumphant return to earth, the actual first spacesuit to walk on the moon received a hero’s welcome nearly equal to that received by the man who wore it—perhaps helped by the fact that the suit may have been more receptive to publicity than the famously press-shy Armstrong himself. It went on a tour of all 50 states with Apollo artifacts, before being transferred to the Smithsonian in 1971 and given pride of place in the new National Air and Space Museum when it opened in 1976. The suit remained on display there until 2006, when it was removed to climate-controlled storage.

On a recent afternoon at NASM’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, where conservators are restoring the suit, it looked as though Armstrong might have moments ago stripped it off and slipped into something more comfortable. Yet the years have taken their toll, particularly on the increasingly brittle rubber lining of the suit’s interior, once responsible for maintaining air pressure around the astronaut’s body. The suit was designed to make it to the moon and back—but not to last through half a century of public display. A garment intended to survive temperature swings of 500 degrees, deflect deadly solar radiation and function at zero gravity is today very fragile. It must now be kept at around 60 degrees, shielded from flash photography and supported against the effects of gravity.

“Spacesuits are such a challenge because they have composites and materials degrading and off-gassing constantly,” says Malcolm Collum, Engen Conservation Chair at NASM. “The suit will eventually destroy itself unless we can get those acidic vapors out and filtered away.” (The rubber lining, for example, exudes molecules of hydrochloric gas as the suit ages.)

The suit was a marvel of engineering and materials science, 21 intricately assembled layers, incorporating components such as aluminized mylar, and Beta cloth–Teflon-coated silica fibers developed for the Apollo mission. Each suit was custom-made for the individual astronaut. The materials were innovative, but many techniques were traditional, including French seams of the type used for wing fabric on World War I airplanes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/e0/79e0e80b-f259-4e2d-9f16-e88983664c00/oct018_a01_prologue_copy.jpg)

In 2015, in anticipation of the approaching 50th anniversary, the Smithsonian began planning to put the spacesuit back on view. The museum launched a Kickstarter campaign, “Reboot the Suit,” seeking to raise $500,000 for the conservation project. The campaign reached its initial goal in only five days and went on to raise a total of $719,779 from 9,477 donors. (The additional funding will pay for restoration of the suit Alan Shepard wore in 1961 during the first manned American spaceflight.)

To minimize manipulation of the fragile artifact, it has been X-rayed, CT-scanned, and probed with a borescope. The suit was lightly cleaned with a filtered vacuum fitted with micro attachments.

“You’re always learning new things,” says Collum. Why is there a different fabric weave here? What is this patch for? Former astronauts could recall only that a suit chafed here or made them sweat there, but for design details, conservators had to go to the engineers who worked for the suit’s original manufacturer, International Latex Corporation, of Dover, Delaware. “We had 11 engineers from the Apollo program at ILC visit and consult with our team,” says Meghann Girard, the Engen Conservation Fellow assigned to the project. One of the few women in the ILC group, Joanne Thompson, had been responsible for much of the experimental sewing. Two rectangular patches on the back, she explained, were added at the last minute over concerns that the life-support system could cause chafing.

When the suit goes on view next summer for the moonwalk anniversary, it will be encased in a state-of-the-art, air-filtered glass enclosure with 360-degree visibility, UV protection and temperature maintained between 60 and 63 degrees. The prototype system, it is hoped, will become the new standard for spacesuit displays.

For conservators, the most powerful experience was simply being in proximity to an object so freighted with history. “It constantly speaks to you,” says Collum. “Imagine a person standing in this suit on the moon, looking back at earth. It’s emotional. You don’t get numb to these sorts of things.”