Eddie Van Halen on How Necessity Drives Innovation

The rock star, who died on October 6 at age 65, said that perfection is boring and mistakes are the “most exciting element of music”

:focal(1728x585:1729x586)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/8a/488a6d39-5908-4813-8bb8-43adf62bd766/gettyimages-490790426.jpg)

Editor's Note, October 6, 2020:Rock legend Eddie Van Halen has died of cancer at age 65, his son, Wolfgang, announced on Twitter.

“[M]y father, Edward Lodewijk Van Halen, ... lost his long and arduous battle with cancer this morning,” wrote Wolfgang in the statement. “He was the best father I could ever ask for. Every moment I've shared with him on and off stage was a gift.”

In 2015, Smithsonian magazine spoke with Van Halen to learn more about his innovative career. Read the conversation, recirculated to mark the musician's passing, below.

For Eddie Van Halen, seminal rock star, inventor, and experimenter, innovation stems from necessity. In 1978, he created the hybrid black-and-white guitar that combined parts from a Fender and a Gibson, transforming the instrument to develop the sound he wanted and needed.

Today, he uses an EVH Wolfgang, also a product of constant reinvention and experimentation, named after his son. Replicas of both guitars along with an amplifier will be donated to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, joining the original Frankenstein 2, which Van Halen donated in 2011.

The avant-garde rocker’s evolution is ongoing—with a pending album and tour in the works, as well as a patent on another musical innovation. He spoke with Smithsonian magazine about the process behind his inventions, his training as a classical pianist and his love of mistakes in music.

What made you want to take a chisel to a guitar and change what was going on in music?

It was just a necessity. What I needed to be able to play the way I do. No instrument existed like that. I had to build my own.

Describe the process behind the innovation of the black-and-white guitar?

At a very early age, when I first started playing guitar, I would go to music stores and everything I played just didn’t do what I wanted it to. I liked the sound of a Gibson, it has a humbucking pickup in it, which is a much fatter sound whereas a [Fender] Stratocaster has a very thin sound, so unless you use some kind of distortion device, I could never get what I wanted out of a Stratocaster. It’s very clean sounding. But…what I liked about the Fender is that it had a vibrato bar and the Gibson did not.

So I went to a custom shop out in San Dimas called Boogie Bodies and they sold a Strat-style body and necks and things like that. I bought a really cheap second—ones they don’t sell that have flaws like a knot in the wood—so I bought a body for $50 and a neck for $75, and I took [the guitar] home and took a chisel and a hammer and started making holes to put a humbucking pickup in it. And then I made my own pickguard and what possessed me to paint it that color, nobody knows.

Some things I came up with out of necessity—like building that guitar, no guitar like that existed.

What are the key differences between that first guitar you made and the modern-day Wolfgang model you built and use now?

It’s a natural evolution of many, many things that I’ve stumbled onto while building guitars—the Wolfgang has a locking tremolo on it and a patented device called a D-Tuna, which works with the low E string—by clicking a switch you can automatically drop down to a D. The frets in my current guitar are made out of titanium so they don’t wear out. And the volume knob is very, very easily turned and really smooth all the way from zero to ten. So there’s no sudden surge like many other guitars.

It also has a kill switch: when you push the button, it cuts off the sound in the guitar completely, so you can do special effects with it. It’s a state-of-the-art guitar, and includes all the things I’ve learned over the years.

Do you see yourself continuing to change parts of it?

I already have come up with another patent—haven’t really pursued it yet—it’s called a D2H, which is a very complicated device that allows you to drop or pre-tune a string and flip the lever and it will drop to that pre-tuned note. And when you flick it back up, it goes back to wherever it was.

Can you talk about your background as an immigrant coming to the United States?

Music has been part of my life since day one. We were exposed to it at a very early age because my father was a musician. My father would be out playing a gig and he would be gone for weeks at a time, which made my mom not really want us to follow in my father’s footsteps, for one. But, we definitely got the bug because we were around music all the time. We trained to be classical pianists. My mom wanted us to do something respectable, if we were to go into that field. At the same time, how many famous classical pianists do you know? That would have been a harder business to get into than the one we’re in.

We showed up in America with the equivalent of about $50 and our piano. My father played on the boat and after a couple of nights of him playing, he asked my brother Alex and I if we would play during intermission. So we played on the boat, too. All of a sudden after that, we were sitting with the captain of the boat having dinner. So, we learned at an early age, the perks of being onstage.

When we came to America in 1962, we couldn’t speak the language, we lived in one room in a house shared with three other families. My father had to walk three miles every day to wash dishes at a hospital. He was a janitor at the Masonic Temple. My mom was a maid. A year into living in Pasadena, California, he began playing with other people on weekends. He played clarinet and saxophone. Music was our common thread that paid the rent, it was a bond in the family. We would not have survived had it not been for music.

Music has been a lifesaver for the Van Halen family. When we graduated high school, everyone else was going off to college. We couldn’t afford to go off to college. We just carried on, doing the only thing we knew how to do.

Why does rock ‘n’ roll lend itself so readily to reinvention?

It’s a feeling, it’s a vibe, it stands for something. Rock ‘n’ roll stems from the blues, but at the same time, there are elements of jazz, which is very free-form. It is more based on a feeling and expression of yourself than it is the actual notes you are playing.

So the curators are going to have to write labels for these pieces you've donated, want to give them a hand? What's your defining contribution, if you don't mind saying so yourself?

The label would have to say: “This is a black and white striped guitar, which changed the industry and how to build guitars because one like that had never existed before and the techniques I came up with playing that guitar had also never been done before. You can hear it in everything from songs like “Eruption” and the intro to a song called “Women in Love,” to others including “Mean Street” and "Cathedral.””

What are your thoughts on the shift in music from traditional records to digital streaming and what that bodes for music, moving forward?

That’s a toughie. When things went digital, everything changed. I still prefer to use tape machines at home as opposed to Pro Tools. Pro Tools is a computer, which is all ones and zeroes. It’s not true. It’s not as warm-sounding and if you make a mistake, it can easily be fixed in the computer. Whereas, I like mistakes.

When we record, we play live altogether. We don’t do one instrument at a time and get it perfect. To me, that’s not what music is about. Music is meant to be heard and seen live. The record is more to remind you of the show you just saw.

Why are the mistakes in music so important?

The most exciting element of music is when someone’s about to lose it, you know? If someone is so perfect…when you see Van Halen live, there’s always an element that keeps you on the edge of your seat. Because, you’re just waiting for it all to fall apart, but it never does. That creates a tension within the band itself, which in turn, creates excitement.

How do you get to that point when you don’t know what’s going to happen next in a performance?

That’s where you just throw all caution to the wind. I have a saying for that: “fall down the stairs and hope you land on your feet.”

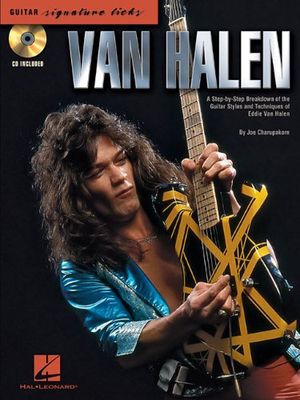

Van Halen - Signature Licks: A Step-by-Step Breakdown of the Guitar Styles and Techniques of Eddie Van Halen

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)