How Will 3-D Printing Change the Smithsonian?

The Secretary of the Smithsonian looks at the many advantages offered by the new technology

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/dc/96dcc137-27e7-4250-9732-aa91a3fa28a3/01-feb14-castle-3d-mammoth.jpg)

Few objects better convey the toll the Civil War took on Abraham Lincoln than the “life mask” cast by the sculptor Clark Mills in February 1865, just two months before Lincoln’s assassination. Craggy facial lines reveal more clearly than any narrative prose could the physical strain placed on the 16th president by four years of war and strife.

What if students studying the Civil War could, in their classrooms, hold that mask and see for themselves this view of Lincoln? That vision is close to reality. While our actual Lincoln mask will stay in Washington, D.C., teachers can now download data from a new Smithsonian website and create accurate replicas for students to inspect using a relatively inexpensive 3-D printer.

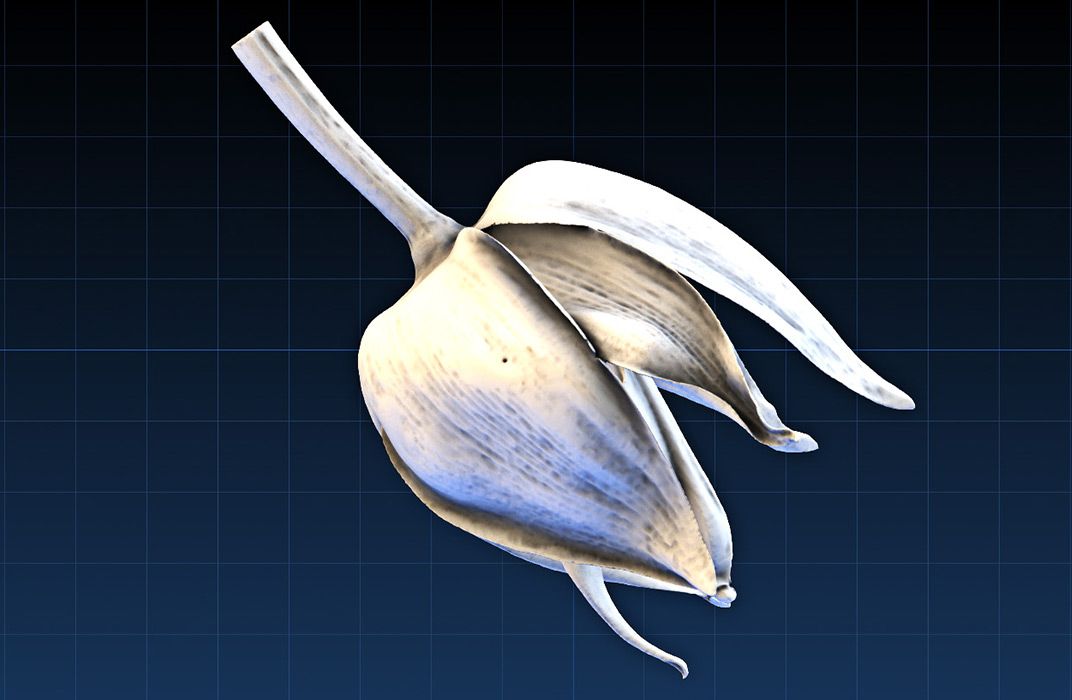

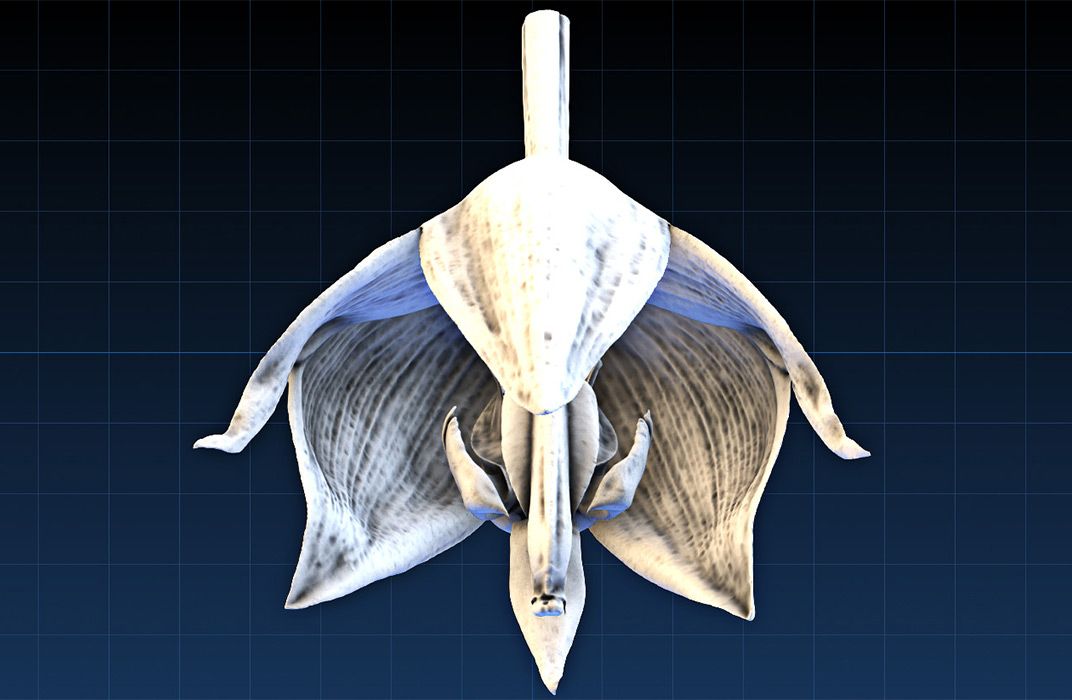

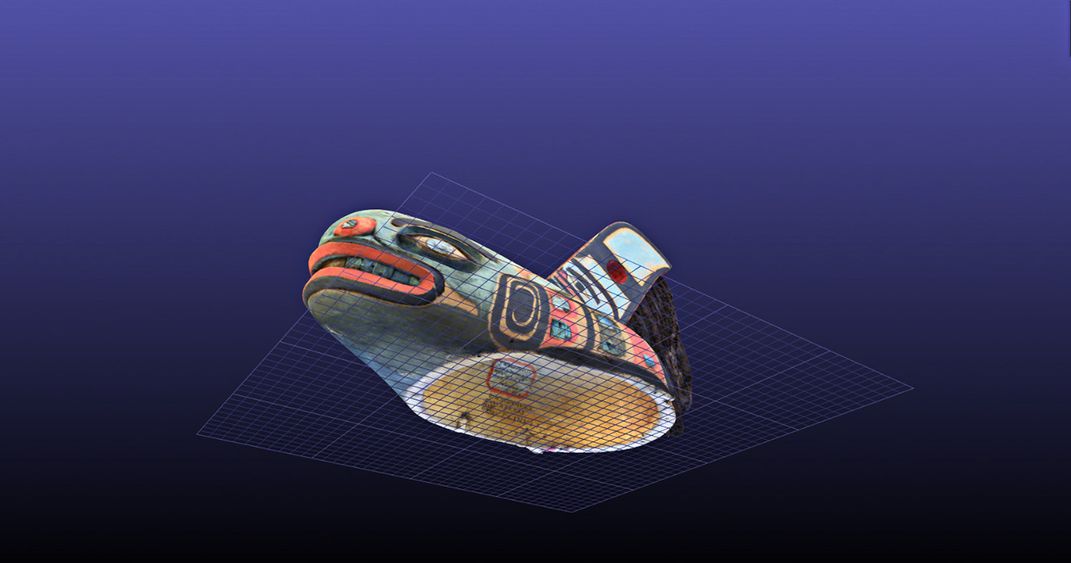

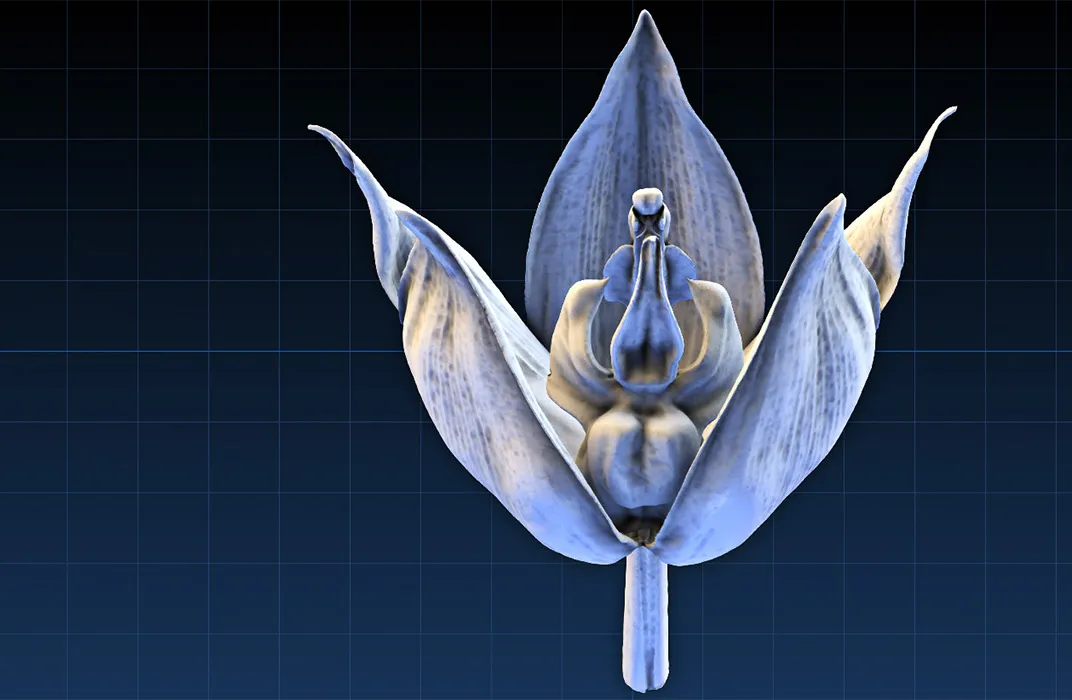

The Lincoln mask is one of 20-plus objects from our collections that the digitization office has placed online as a demonstration of the potential of 3-D scanning. Others include the Wright Flyer, a woolly mammoth skeleton, a sixth-century Chinese statue known as the Cosmic Buddha, a supernova remnant and a bee.

Using most standard web browsers, our online viewing tool, called the 3-D explorer, lets you rotate specimens, zoom in, create cross-sections and accentuate textures. In the week the site went live in November, 100,000 people visited 3d.si.edu, as many as visited our main portal, si.edu.

Smithsonian X 3D, our name for all endeavors related to 3-D scanning, is a boon not just to educators but to scholars, too. The five-foot-tall limestone Cosmic Buddha, for example, is covered in detailed carvings depicting Buddhist “realms of existence,” which can be hard for even experts to decipher. Our curators say that with the aid of the viewer, they are seeing nuances in the scenes that have eluded researchers for centuries.

At a conference hosted by the Smithsonian on the launch of our 3-D initiative, I was introduced to the technology by being scanned myself. I tentatively stepped onto a slightly elevated octagonal platform, surrounded by 80 cameras mounted on metal poles, wondering aloud if I was about to be transported to another dimension. But the process was, from my end, as simple as getting a picture taken, and the next day I was holding a six-inch-tall likeness of myself, printed in a plaster-like substance.

Three-dimensional imaging will allow us to take irreplaceable, one-of-a-kind artifacts heretofore seen only in museums and, in a sense, put them in the hands of learners around the world. A day after the website’s launch, a reader of a popular science-fiction blog posted a digital rendering of Smithsonian’s woolly mammoth within an ice-age scene of his own creation. That’s exactly the kind of playful experimentation we’d hoped the 3-D explorer would inspire, and we can’t wait to see what else you come up with.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wayne-clough-240.png)