How Dan the Zebra Stopped an Ill-Fated Government Breeding Program in Its Tracks

At the centennial of the death of this captive animal, an archaeozoologist visited collections at the Smithsonian to examine human-animal relationships

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/aa/baaa263d-68cd-4b04-84cd-1f8d655b7758/dan_zebra.jpg)

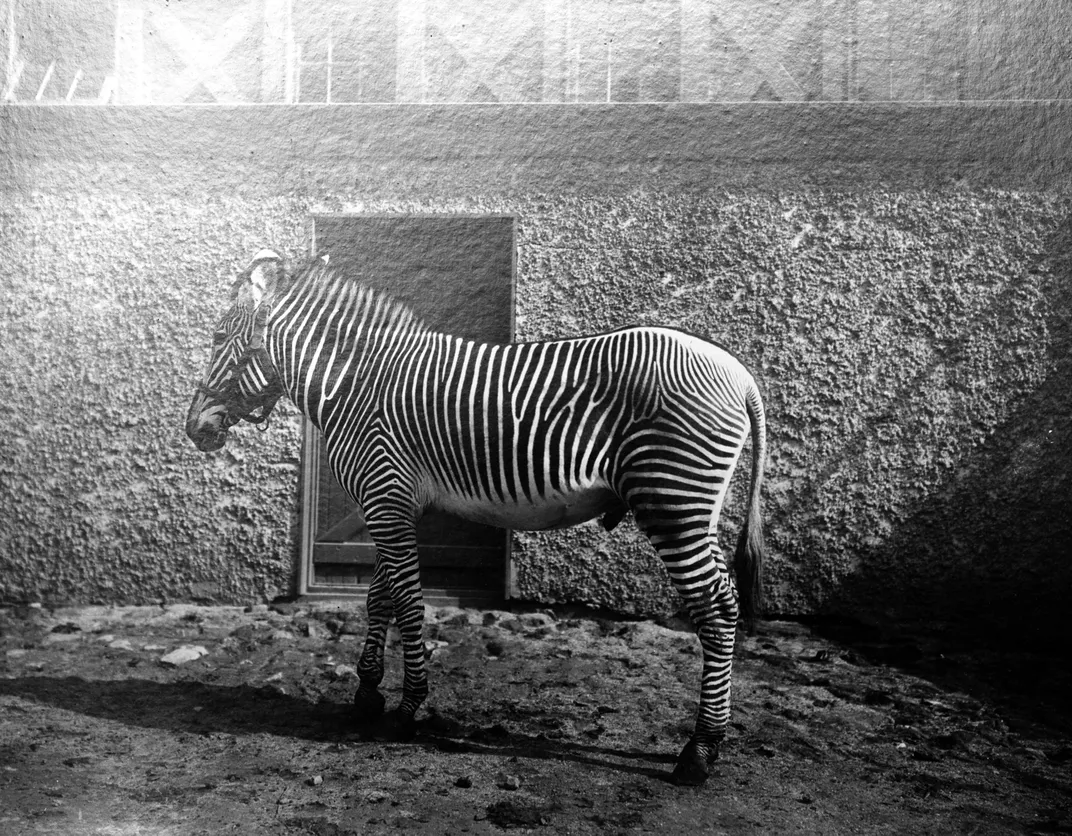

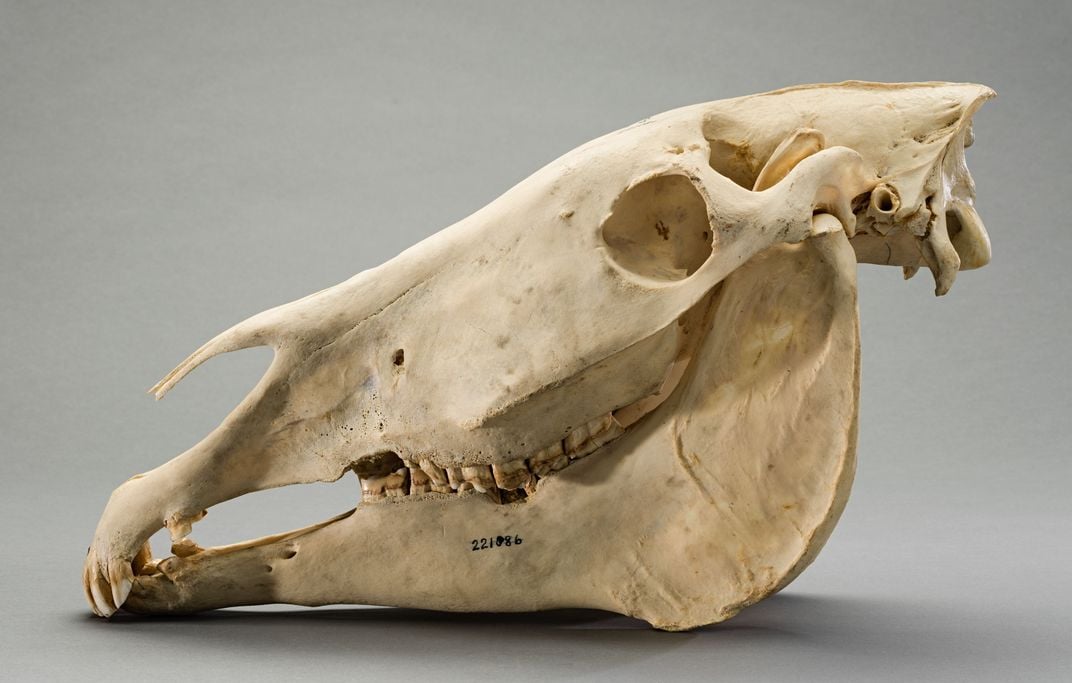

The skeleton of NMNH 221086, sometimes referred to as “Dan,” resides in a steel cabinet in a dimly lit storage room at the Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center in Suitland, Maryland. The skeleton is a male Grevy’s zebra (Equus greyvi) that was born in the kingdom of Abyssinia (now northern Ethiopia) in the early 20th century. In 1904, Abyssinia’s King Menelik presented the four-year-old zebra as a gift to President Theodore Roosevelt. Dan was soon transported to America—the first chapter in a strange journey that holds some important lessons for human history.

With technology and geopolitics changing at a faster and faster pace, the late 19th and early 20th century saw people, plants and animals moving between continents like never before, including the colonial and imperialist expansions of the western world into Africa, Australasia and the Americas. Before motorized vehicles, much of this expansion was powered by hoofbeats—horses were not only transportation, but also still played a key role in military infrastructure, agriculture, industry and communication.

However, some areas of the world, such as equatorial Africa, were hostile environments for horses. This region, known for its notorious tsetse flies and parasitic diseases like trypanosomiasis, presented extreme biological barriers to large livestock—leaving many dead nearly on arrival to low-latitude portions of the continent.

Against this backdrop, some western eyes turned to the zebra. With immense physical strength and stamina, the zebra by comparison to the horse and other equine brethren, is well-adapted to African climates and the continent’s fatal diseases.

As Western interests in Africa and other challenging climates for livestock transport expanded, these traits raised questions about whether zebras might be domesticated. Arriving in the U.S., Dan quickly became the focus of a government program that sought to domesticate the zebra by cross-breeding the animals with domestic horses and donkeys.

It didn’t go well. Dan was unruly, known for attacking his caretakers, and uncooperative with efforts to cross-breed with other equids. A 1913 summary of the program, published in The American Breeder’s Magazine, describes how Dan refused the mares brought to him. Dan was said to have “a positive aversion” to his horse counterparts, and when one was let loose in his paddock, he “rushed at the mare, and would undoubtedly have killed her had he not been driven back into his stall.” He did, however, ultimately mate successfully with a number of jennies (female donkeys).

Other zebras were brought in to supplement the program, and crossed with southwestern burros (feral donkeys) to produce zebra-ass hybrids with a more suitable and less dangerous temperament. Jennies were also used to collect material, and perform artificial inseminations of female horses. Unfortunately, these second-generation animals showed little inclination to work as riding or draft animals, and were also infertile so that producing another generation required repeating the cross-breeding process from scratch.

After its many trials and tribulations, the program eventually ran out of funding and enthusiasm. The zebra domestication program proved to be an absolute failure.

Dan was sent to the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, where he lived out his days until his death on December 14, 1919. His remains became a part of the scientific collections at the Smithsonian, where they this year mark their 100-year anniversary.

After Dan’s death, the dream of an American domestic zebra died as well.

But why were some animals domesticated, and others not? This zebra’s tale may actually hold important clues into the deep history of horse and animal domestication. A similar process of capture and experimentation with animal breeding, captivity and use must have played out countless times over human history. However, in the end only a handful of large animals—among them horses, donkeys, llamas, camels and reindeer—were successfully domesticated (meaning that after generations of breeding, they become dependent on humans for their upkeep) for use in transport, while other hooved animals like the zebra, the moose, the elk and the deer remain undomesticated.

Scientists have long considered the earliest horse domestication took place among an ancient population of animals from Botai, Kazakhstan—these were believed to be the first ancestors of the domestic horse (E. caballus) and the first to be managed, ridden and domesticated. But in 2018, research by geneticist Ludovic Orlando and his team showed that the Botai animals were not the ancestors of modern domestic horses, but rather of today’s Przewalski’s horse (Equus przewalskii), a closely related sister species that has never, in later periods, seen use as a domesticate.

About 5,500 years ago, the people of Botai subsisted almost completely on these horses. Their tools were made from horse bones. Archaeological evidence suggests the horses were part of ritual burials. They may have even kept them for milk.

However, the domestication of the Przewalski’s horse—if it can be called domestication—did not last across the centuries and Equus przewalskii returned to the wild, while Equus caballus proliferated across the globe as a highly successful domesticated animal.

The strange 20th century efforts to domesticate the zebra offer a plausible explanation: perhaps, like their striped cousins, Przewalski’s horses were too unruly to justify a sustained, multigenerational process of captive breeding.

The zebra was not a complete failure as a domestic animal. While few zebras were effectively trained for riding, many did find their way into transport infrastructure as members of driving teams in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Anecdotal accounts suggest that the animals were more effectively controlled in team harnesses, particularly when they could be paired with more docile mules to mitigate their wild behavior.

Its successes may be even more instructive in understanding the earliest horse domestication. A major lingering mystery is that, beginning with their first appearance in archaeological sites or ancient records, there is, in fact, very little evidence of horses being used for riding. From the frozen steppes of ancient Russian and Kazakhstan, to the sandy ruins of ancient Egypt, or the royal tombs of central China, the first horses are nearly always found in teams, usually with chariots.

If the first domestic horses were behaviorally similar to the zebra—disagreeable, violent, and dangerous—pulling carts may have been the only practical form of transportation available to ancient horsemen. In this scenario, it might have taken centuries of breeding and coexistence between human and horses before behavior, knowledge and technology reached a point where riding on horseback was safe and reliable.

Sorting out these possibilities will take many lifetimes of work, but fittingly, Dan and others like him may still have an important role to play in finding the answers. Without historical records, and with few other kinds of artifacts available from crucial time periods, of the most useful data sets for studying domestication come from the study of the animals’ bones themselves—a discipline known as archaeozoology.

Over recent decades, a growing number of researchers have sought clues to the domestication process in the skeletal remains of ancient horses. Robin Bendrey, a professor at the University of Edinburgh is one of these researchers. To find answers in ancient bones, Robin and his colleagues spend countless hours studying the skeletons of modern horses, donkeys, zebras and other equids with well-documented histories and life experiences.

“The study of modern skeletons of animals with known life histories is crucial,” he says, “Because it allows us to understand the different factors that influence skeletal variation and abnormality. We can then use these comparative data to investigate pathology in archaeological remains and make robust interpretations about past human-animal relationships.” By looking at bones of individual animals, Bendrey and others have been able to trace skeletal features linked to human activity, like bridling or riding, that can be used to trace the process of domestication in assemblages of ancient bone.

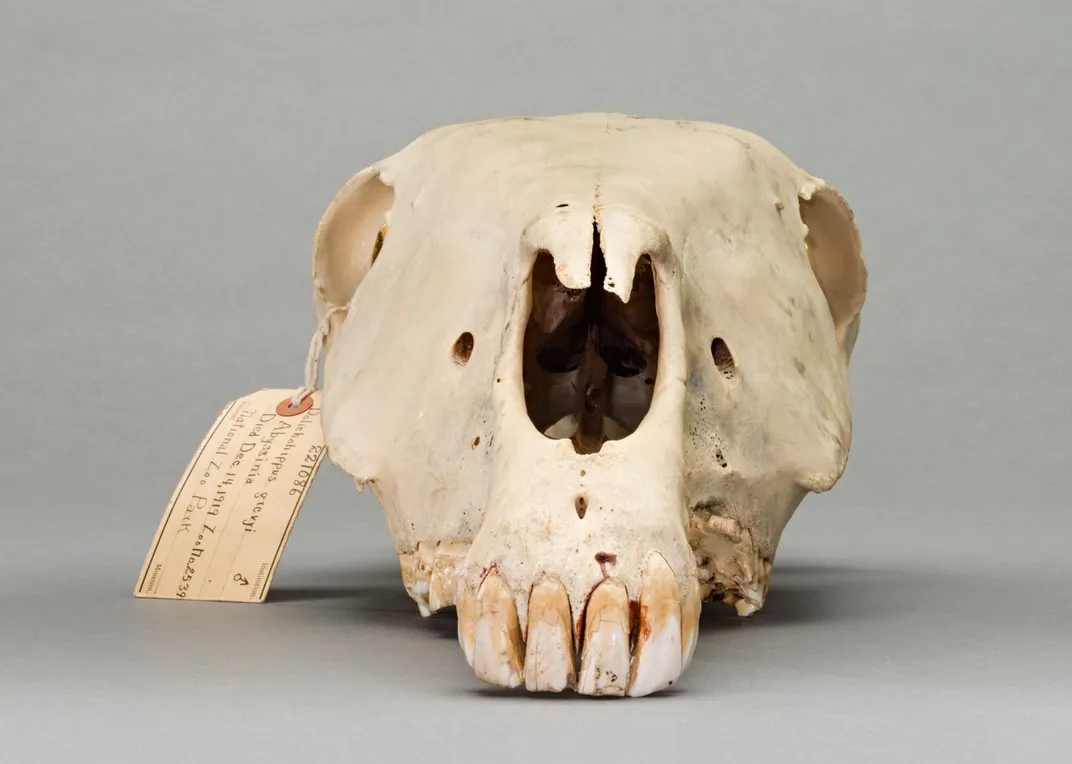

Today, Dan’s skeleton preserves a number of interesting clues into his life that may help future researchers understand domestication. While the skeleton of a wild equid is usually relatively free of major problems, Dan’s teeth are worn irregularly—a common issue in animals that were feed an artificial diet rather than gritty natural forage. Dan’s skull also shows several kinds of damage from a harness or a muzzle. This includes warping of the thin plates above his nasal cavity, new bone growth in on the front margins of the nasal bones, and wearing away of the nasal bones thin from a bridle/halter noseband. By documenting issues like these in modern natural history collections, archaeozoologists can expand their analytical toolkit for identifying domestic animals, and understand how they were fed, bridled and harnessed, or otherwise used by early people in the deep past.

William Taylor is a specialist in the study of archaeozoology and horse domestication. He serves as assistant professor and curator of archaeology at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History. He was assisted on this story by Seth Clark as part of his 3D Fossil Digitization Internship at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.