How Smithsonian Helped Solve the Twitter Mystery of the Unknown Woman Scientist

Sheila Minor was a biological research technician who went on to a 35-year-long scientific career

:focal(213x91:214x92)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/61/3a610250-6fcd-4ce7-81de-819456107460/sheila.jpg)

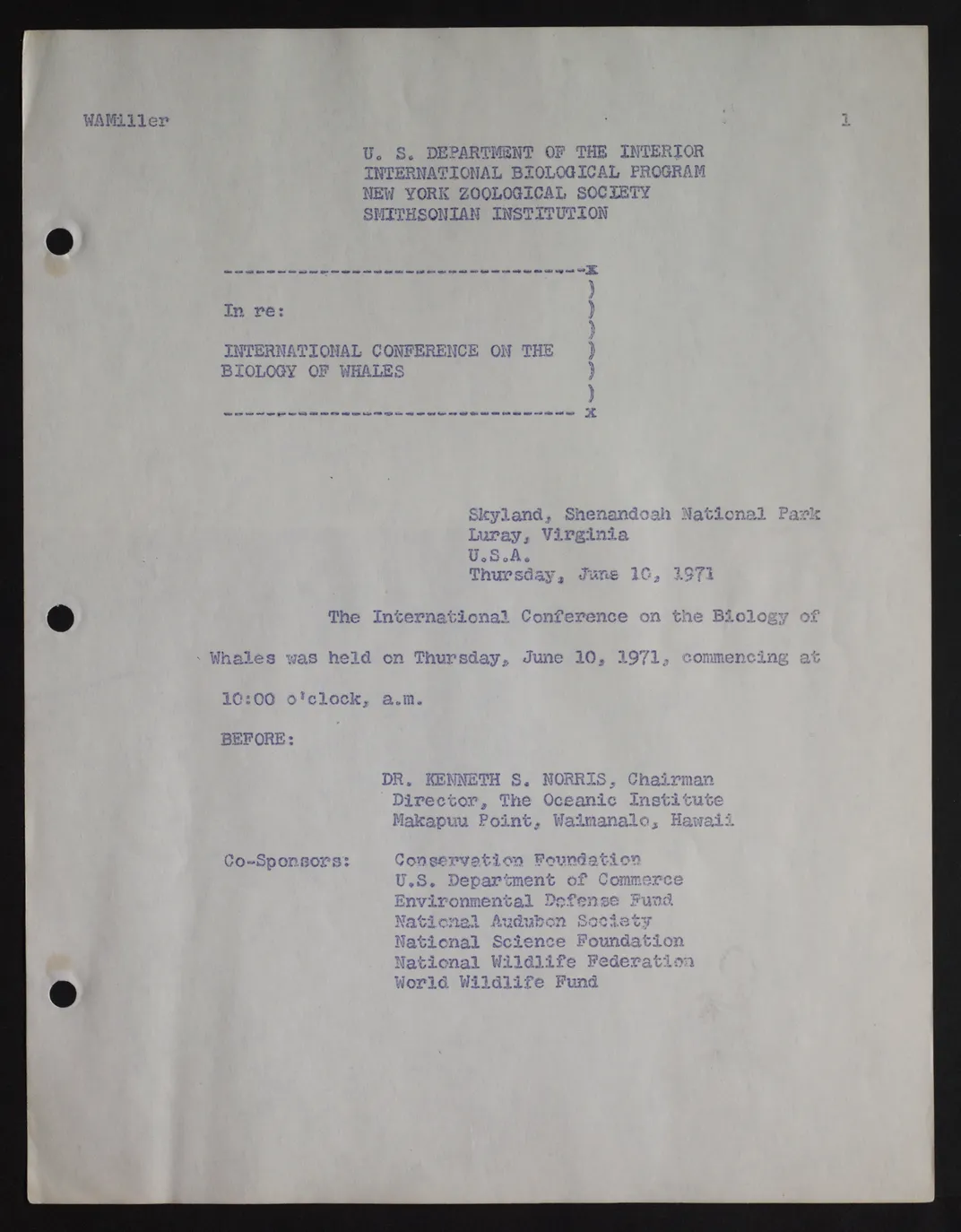

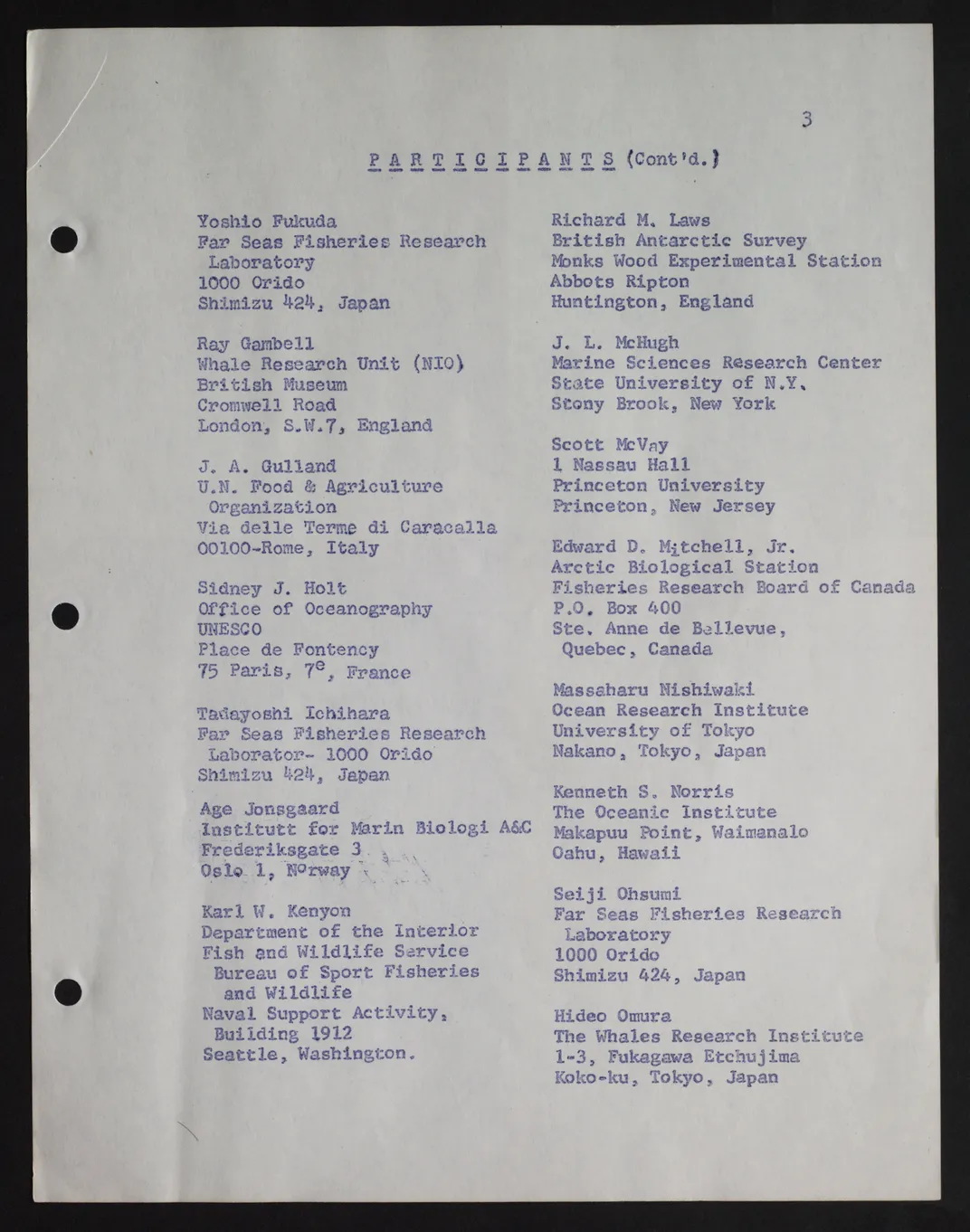

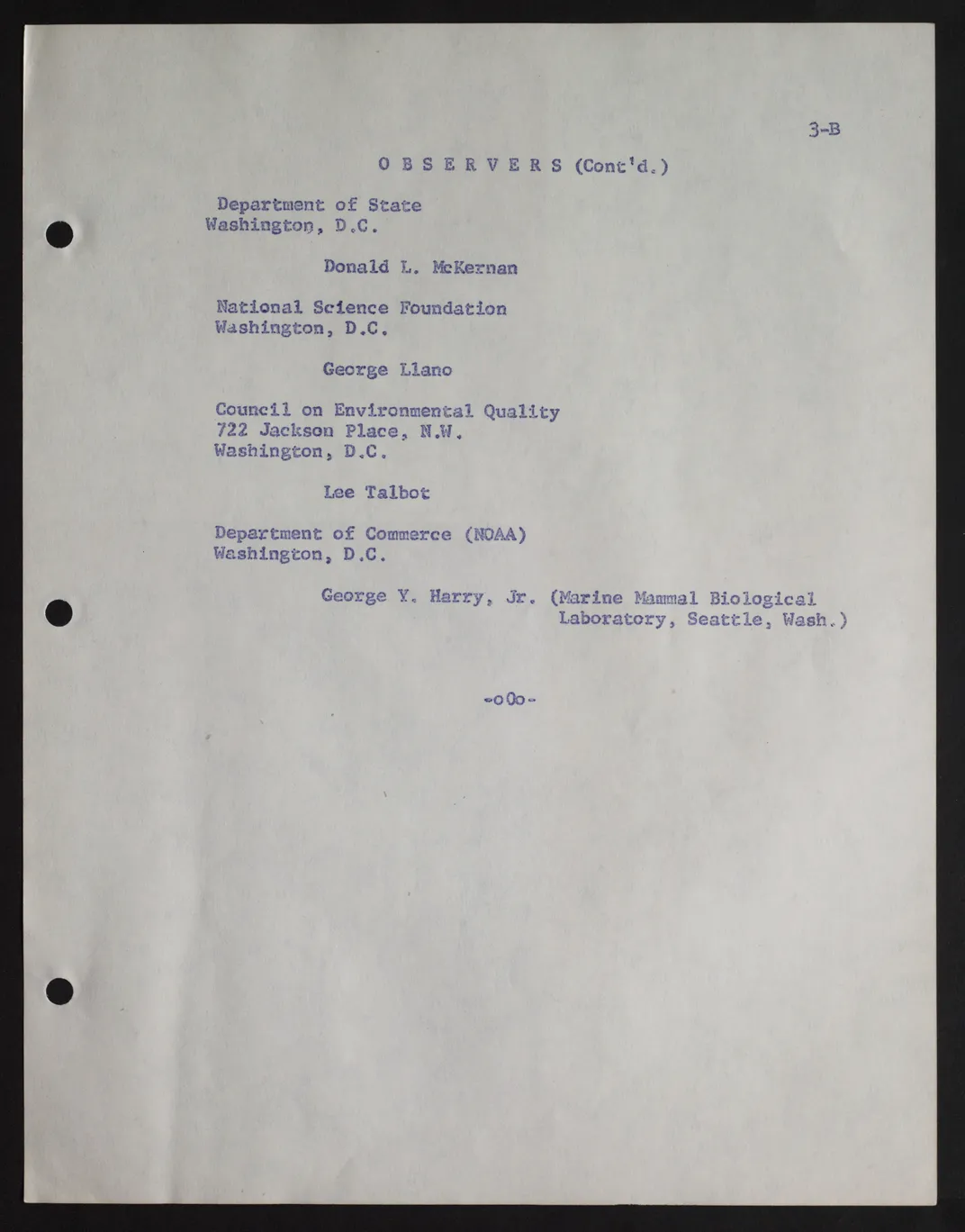

Illustrator Candace Jean Andersen was researching a picture book on the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 when she came across a photograph taken during a scientific conference. Her eyes locked on the only woman pictured, who also happened to be the only person who wasn’t identified in the photo by name and title.

“Seeing this lone woman in the group, I wanted to know who she was,” Anderson tells Smithsonian.com. “Surely she’s of some importance if she’s at this conference.”

The picture haunted her. A few weeks after she first saw the photo, she took to Twitter. “Can you help me know her?” she asked her 500 followers. She shared the full photograph and a cropped version that zoomed in on this mystery person: a pixelated magnification of a black woman wearing a headband, her face partially obscured by the man standing in front of her.

Her literary agent retweeted her. So did a zoologist friend. Soon, the responses started pouring in.

Candace, there's conference proceedings of the 1971 International Conference on the Biology of Whales. It was printed in 1974. You can buy it for $15: https://t.co/5icgdX1Fko

— Su (@smithjosephy) March 10, 2018

I can’t resist a mystery, and this one has me googling like mad. No name for you, but I’m learning a lot about 20th century black women scientists. Very cool!

— Matilda (@mfortuin11) March 10, 2018

Women of color amplified that message, and helped to narrow down the search, opening up a conversation on her race.* By Saturday, the post had gone viral, and Andersen had to turn the notifications off her phone.

The search to identify “hidden figures”—a term popularized by the 2017 Oscar-nominated film and its book inspiration, about a team of black women mathematicians at NASA whose work was never recognized—has gained new attention in recent years. Efforts by historians, researchers and the general public have begun investigating the stories behind unsung women, particularly women of color, and writing their accomplishments back into the mainstream narrative.*

Andersen’s effort tapped into that energy, leading history enthusiasts, professional historians and archivists down the rabbit hole.* Perhaps, some suggested, she was Matilene Spencer Berryman, an oceanographer who was also an environmentalist and attorney, and who died in 2003. But others quickly pointed out that Berryman would have been in her early 50s when the photograph was taken, while the woman in question appeared to be much younger.

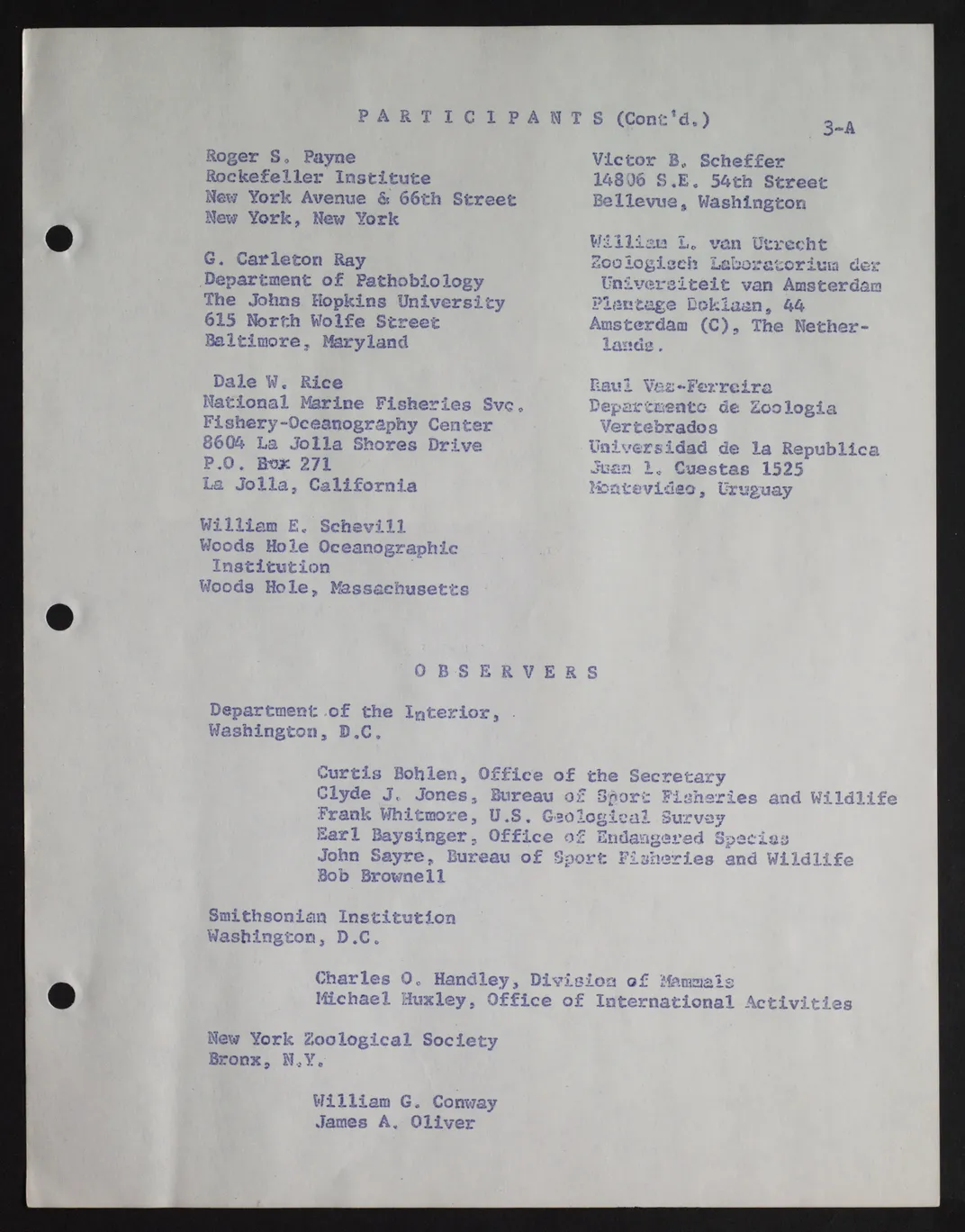

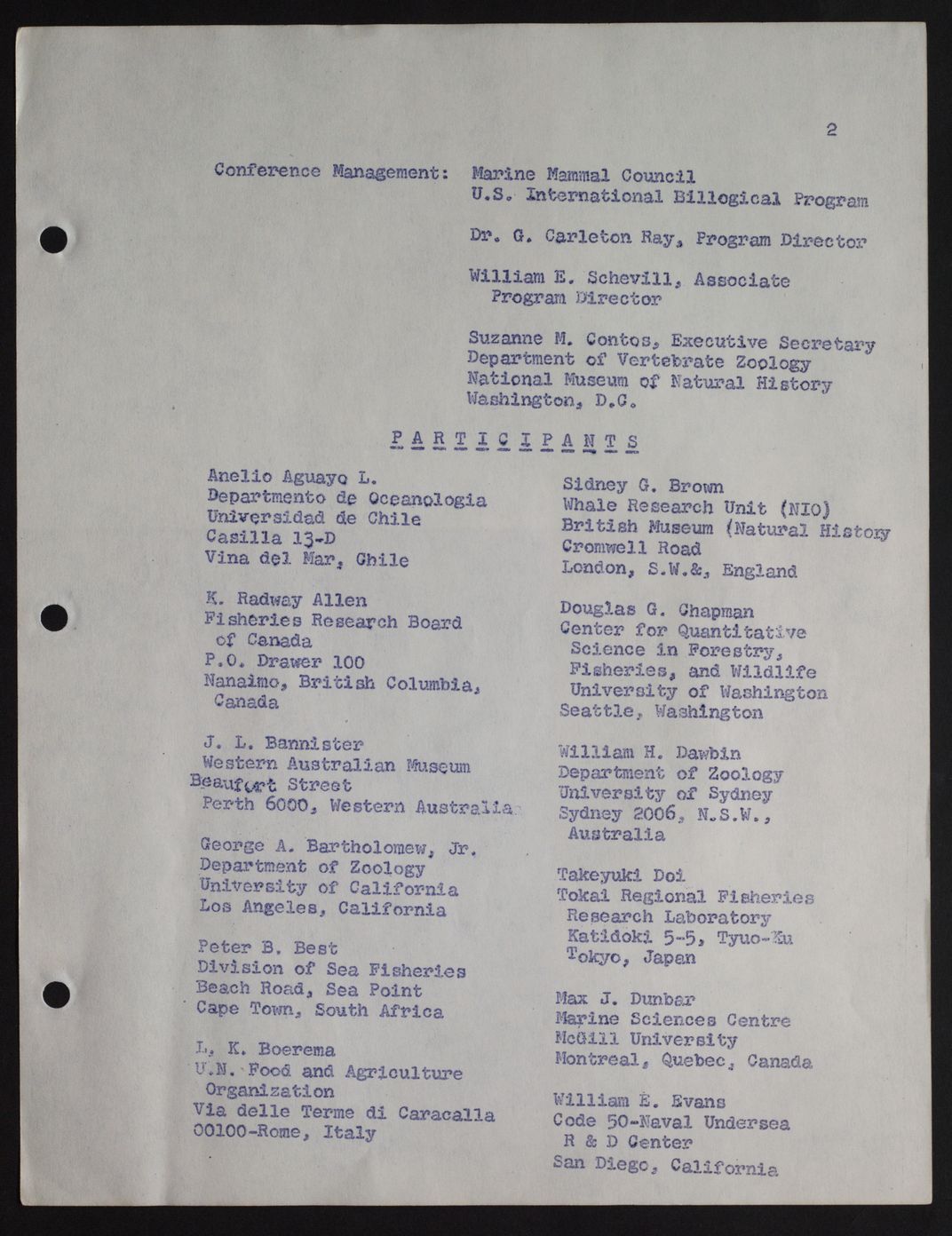

Twitter users also floated Suzanne Montgomery Contos, the executive secretary who organized the conference in question, the 1971 International Conference on Biology of Whales, as the possible mystery woman. But no: Contos, herself, ultimately chimed in on the thread to say it wasn’t her.

Finally, users floated the name Sheila Minor (then Sheila Jones).

Dee Allen Link, a Smithsonian research associate at the National Museum of Natural History’s Marine Mammal program, saw the Twitter thread over the weekend. She had a feeling one of her colleagues might be able to help identify the mystery woman. Since Smithsonian was one of the sponsoring institutions for the conference, she checked in with some of her mentors who she suspected would have been there that day themselves.

She was right. Don Wilson, a curator emeritus of mammals, recognized the woman as Minor, who he said worked for Clyde Jones at Fish and Wildlife Services in the early 1970s.

Contos confirmed the name. She had reached out to her former boss, G. Carleton Ray, who had actually taken the photo. Both Wilson and Ray, however, thought Minor was “support staff.”

Andersen didn’t want the trail to end there.

Suzanne Contos thinks we've hit a dead end.

— Candace Jean Andersen (@mycandacejean) March 12, 2018

Bob and Don think Mystery Woman's name is most likely Sheila Minor.

What do you think, Twitter?

Do we assume she's Sheila?

— Candace Jean Andersen (@mycandacejean) March 12, 2018

Do you think the photo was a quick snapshot, and she just happened to be there?

I wonder what all her papers are?

Did she significantly contribute to the conference?

If she worked for Fish & Wildlife Services then, I wonder what she's doing now? pic.twitter.com/DrY3YzXJmW

By Sunday night, the thread had unearthed several social media profiles she thought might belong to the woman in question. Before she went to bed, Andersen reached out to the person she suspected to be Minor by Facebook. When she woke up, she had a message from Minor (who has since remarried, but has chosen to keep her current last name out of the public eye) waiting. It included an email address and the promise “We have so much to discuss.”

“I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, she’s a living, breathing woman,'” she says. “And she had responded with the heart eyes emoji and the ‘OMG’ so she’s got personality. She’s real.”

As Andersen waited to hear more, the Twitter thread caught the eye of Deborah Shapiro, a member of Smithsonian’s archive reference team, who flagged the potential Smithsonian connection. When she got into the office Monday, Shapiro found that Smithsonian’s own outreach team had also flagged the thread.

“We haven’t had a viral thread come to us as long as I’ve been here,” Shapiro says. While the research and outreach teams have worked independently to unearth women affiliated with the Smithsonian who have been obscured from history, they also rely on the public for help. “We need outside researchers to come in and ask us questions to connect some of the dots for us,” she says, “because there are so many of these stories that have yet to be revealed.”

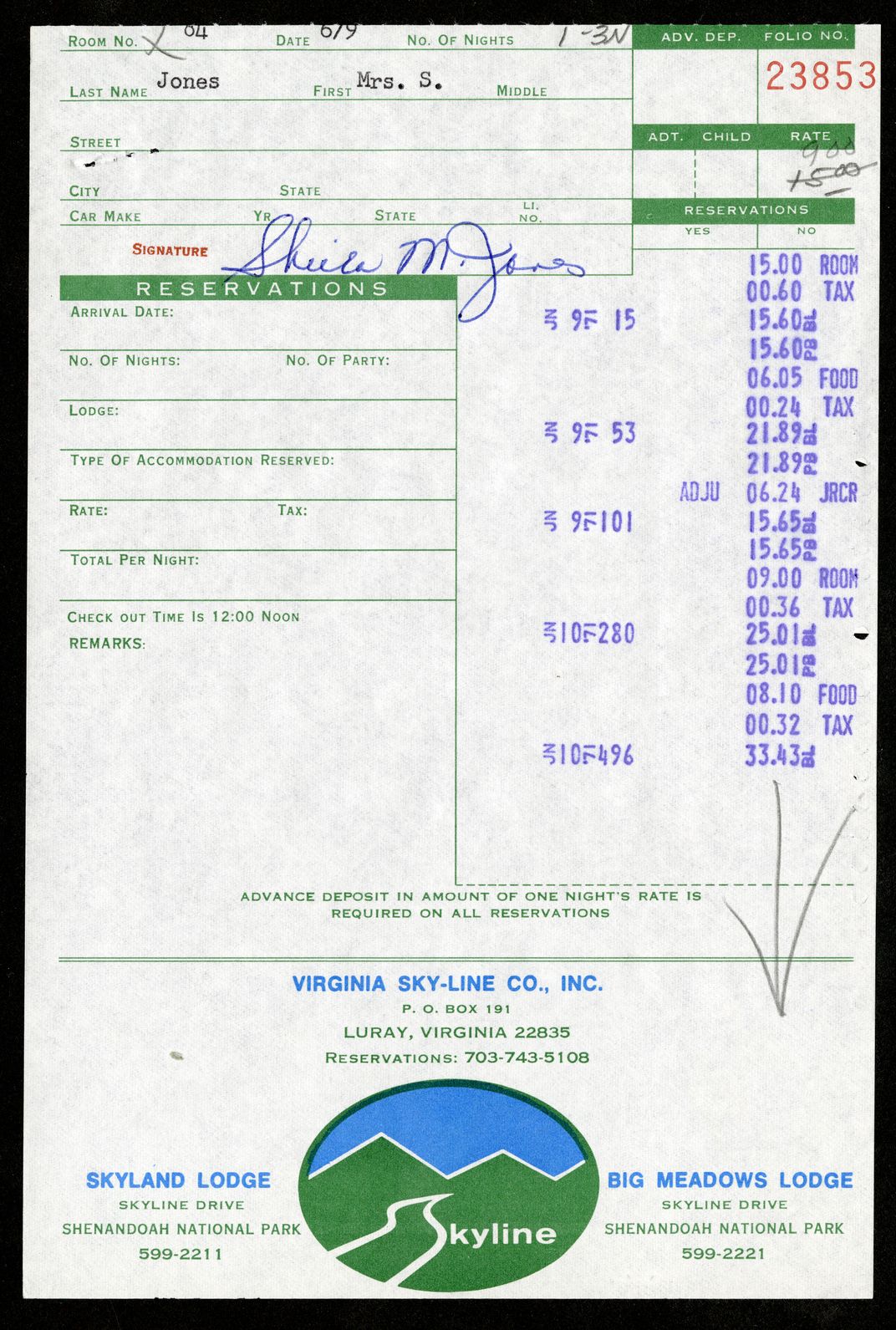

It turned out that the archives did have a folder titled “Sheila Minor, 1972-1975,” which they arranged to have sent in from off-site storage. Meanwhile, they tracked down papers on-site that included the receipts from the hotel the conference attendees stayed at. One of them listed a Sheila M. Jones. Bingo.

“That was really exciting to see,” says Shapiro.

The image proved that she was there at the conference. But when the archivists got their hands on Minor’s file this week, they were able to fill in more details to her story. Minor wasn’t there as an administrative assistant; she was a biological research technician with a B.S. in biology. This was her first job with the federal government in what would become a 35-year-long career at various federal bureaus.

She went on to earn an environmental science master’s degree at George Mason University, and collaborated with K-12 schools to improve science education. In the next two years she participated in a two-island study researching mammals of the Poplar Islands, and presented her findings at the American Society of Mammalogists Meeting in 1975.

Shapiro says the fact that Minor was initially dismissed as an administration assistant made the ultimate reveal all the sweeter. “There’s so much unconscious bias—maybe even conscious bias—because she happened to be a black woman in the photo,” she says. “It wasn’t until I got the biofile back from offsites I saw that, no, she was really a scientist and she did research of her own.”

Moreover, Minor’s omission from the photograph tells a larger story of women in science who have been “not identified” throughout history. “There are all these pictures I haven’t ever seen of women whose names were lost,” says Andersen. “Then there’s women who weren’t even photographed, hustling and likely not credited. It’s kind of intimidating the amount that we don’t know.”

Andersen didn't start out this journey to help put women's stories back into history. But now she says she feels energized, citing the Smithsonian Archives’ ongoing Wikipedia edit challenge, which is continuing the work to shine a light on more of these women.

“Who’s next?” asks Andersen.

*Editor's Note, March 19, 2018: This article has been updated to specify that the "hidden figure" movement centered around writing women of color back into history. It also has been updated to note that women of color helped amplify the Twitter thread, and that professional historians, archivists and librarians contributed to the search, in addition to amateurs. The piece has been updated, and Smithsonian.com regrets the omissions.