The father’s presence in the history of art isn’t nearly as prominent as that of the mother, especially as centuries of Western art was built around images of Madonna and child. Yet one of the most enduring images in art is that of God reaching down from heaven to spark life to the reclining figure of Adam. Michelangelo’s famous pose on the ceiling of the recently-reopened Sistine Chapel is thought to be inspired by the medieval hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus,” which mentions the digitus paternae dexterae or “finger of the paternal hand.”

At more than a dozen museums of the Smithsonian Institution, a sense of fatherhood can be found among some 6,000 artworks, objects and artifacts. Sometimes the depictions are anonymous and oblique, others are intensely personal. Some artists borrow from ancient myth; others depict recognizable figures of history or of contemporary life. And while some deftly chronicle the father’s role in a changing society, others draw from their own childhood memories. “As a child I loved my mother, feared my father, chased grasshoppers, killed snakes and ran naked through the woods,” said the painter Robert Broderson, whose work from the Smithsonian American Art Museum is among those below.

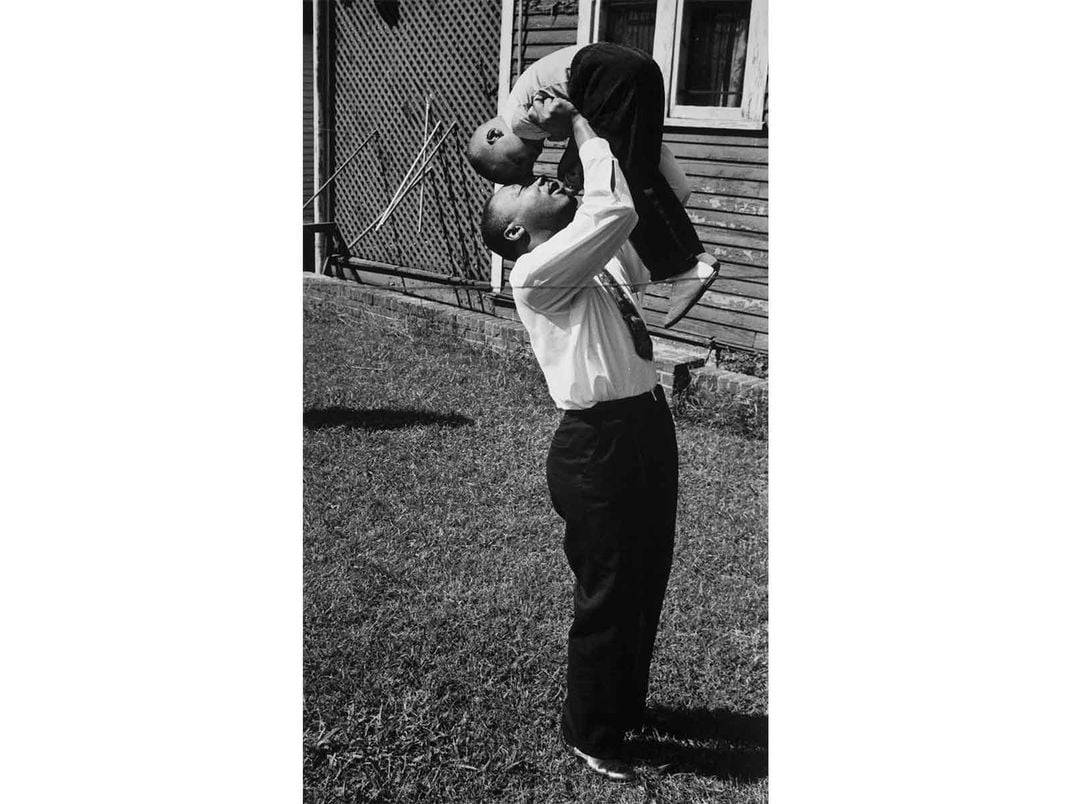

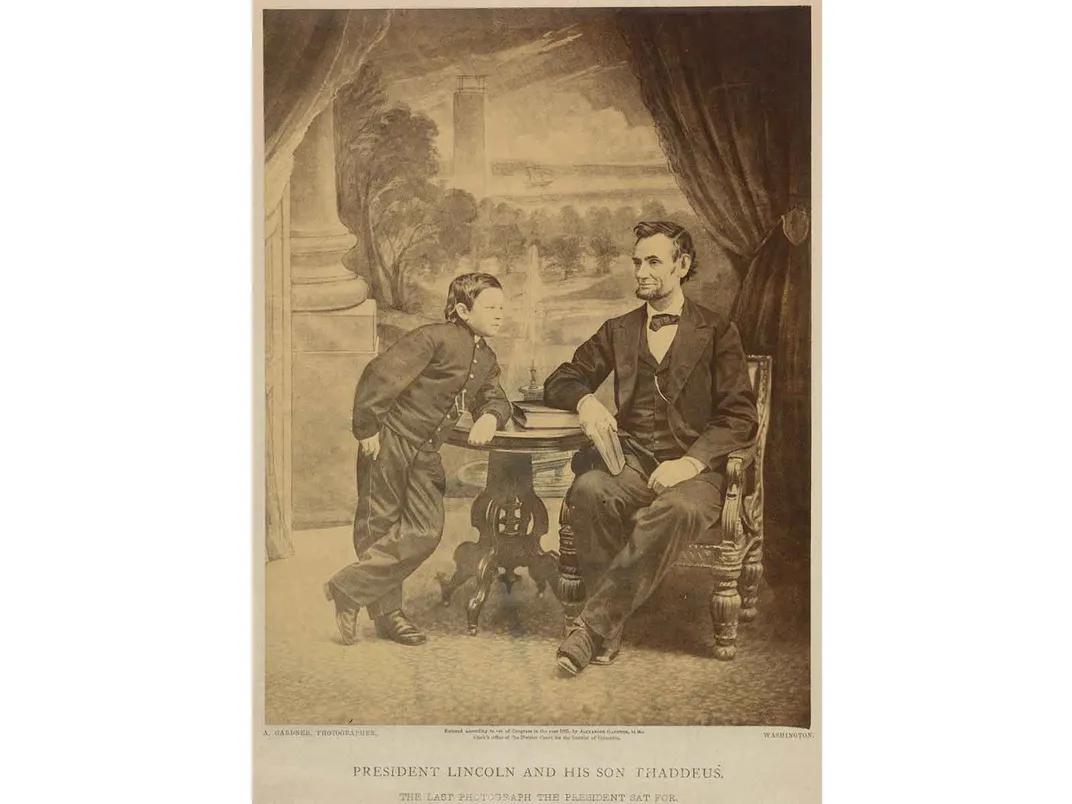

Instantly recognizable among the images are those of Abraham Lincoln, whose bond with his young son Thaddeus only became stronger after another son, Willie, died suddenly of typhoid fever three years earlier. The playfulness and love between father and son denoted in the otherwise formal White House shot by Alexander Gardner is reflected in the photograph of the Civil Rights champion, Martin Luther King Jr., lifting his young son aloft. Only recently has there been an effort to rectify the long-overlooked role of black men in fatherhood; photographer Zun Lee went on a four-year mission to depict the loving connections between African-descended parent and child, even if a father no longer lives with their family “but is nonetheless taking his parenting role seriously.” Likewise, J. Ross Baughman’s depiction of a pair of loving fathers for Life magazine broke normative barriers and expectations in the earlier days of gay rights.

Smithsonian museums remain closed due to public health precautions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. But we culled images of paintings, photographs and etchings from the Institution’s online resources, free for all to peruse. Famous or commonplace, the subjects convey the same undeniable bond we can all celebrate as another Father’s Day rolls around.

Deep South (or) Father and Son by William H. Johnson

The American painter William H. Johnson (1901-1970) was becoming known as a modernist painter of some note after he moved to Europe in the late 1920s. He returned a decade later as war clouds were looming, and started to draw on subject matter from his youth in Florence, South Carolina, where his family still lived. At the same time, his painting style became more and more simplified. This painting came during a troubled time in his life between a 1942 studio fire and the death of his wife in 1944. Things got worse; he spent his final 22 years in a mental hospital and never painted again.

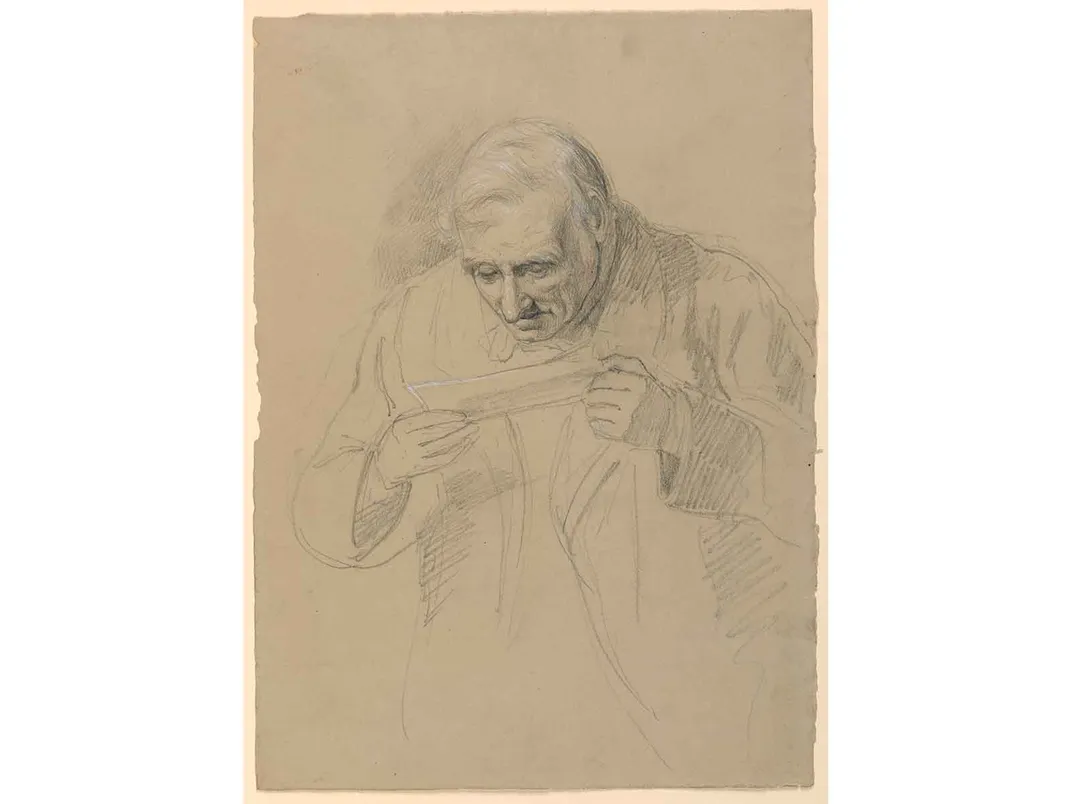

Portrait of the Artist’s Father by Daniel Huntington

A New York artist with deep roots in American history—one grandfather was the first U.S. representative from Connecticut and delegate at the Second Continental Congress; his other was a general in the Revolutionary War—Daniel Huntington (1816-1906) was a member of the Hudson River School of landscape painters before he concentrated on portraits. One of his frequent subjects was his father Benjamin Huntington Jr., who is seen in this delicate 1859 drawing, from the collections of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, straining to read a piece of paper. In a subsequent 1889 engraving, the squinting has subsided; the elder had acquired some wire-framed glasses to assist reading the book before him.

Father Figure: Untitled by Zun Lee

This photograph, from about 2011, may be the most recent in our survey. It is part of a series by Toronto based photographer Zun Lee, who learned later in life that his own biological father was African-American. Born to a Korean mother, he had felt at home with the African-American families on nearby military bases when he was growing up in Germany. “On the one hand, I had become part of the ‘absent black dad’ narrative and its persistent stereotypic visual tropes,” Lee told an interviewer in 2014. “And on the other hand, I had lived an experience of black men and families being loving, present and supportive; the exact opposite of what stereotypes will have you believe.”

Samson Threatening His Father-in-Law by Georg Friedrich Schmidt

Not all gestures in art depicting fatherhood are friendly. Here the Biblical figure Samson raises a fist to his father-in-law, who is peeping his head out a window with some alarm. The 1756 engraving by the German artist Georg Friedrich Schmidt, also from the Cooper Hewitt, reverses the image of an oft-copied 1635 painting by the Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn, which now hangs in Berlin. But as historian John I. Durham has noted: “Samson’s threat was actually a threat of damage to the Philistines, not his father-in-law.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Martin Luther King III by James H. Karales

James H. Karales was hired by Look magazine to photograph the civil rights movement, starting with a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee resistance training session in 1960. He gained unprecedented access to movement leader Martin Luther King Jr. and his family, helping to round out a man known for his stirring oratory and convictions, but perhaps not as much for his warm fatherhood. Here, in a photograph from 1962, King lifts his son Martin Luther King III over his head for a little inverted eye to eye in an Atlanta backyard. The photograph is from the collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

My Father’s Store by Harry Lieberman

Bored in retirement out on Long Island, Harry Lieberman began painting at age 74. The prolific folk artist did a lot of work with Biblical subject matter and Judaica, but he also had a lot of memories on which to draw—including his own career running a confectioner store. But it was his father’s store, with its barrels and shelves of goods that animates this oil on fiberboard work from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. With a disarming perspective that reflects both the stacked boxes and the wide wooden flooring, the customers seem at first to be lying down. He once painted a much more specific biographical portrait of his father with the detailed title My Father Holding a Cigarette (He Was 87 When Hitler Killed Him). Painting helped Lieberman live an extraordinarily long life; he died at the age 106 in 1983.

Abraham and Tad Lincoln by Alexander Gardner

Born in Scotland and trained as a jeweler, Alexander Gardner got interested in photography when he saw the work of Mathew Brady at "The Great Exhibition," the first world’s fair, in London in 1851. He came to the U.S. to work with Brady and was eventually put in charge of his Washington, D.C. gallery before going into portrait photography himself. He gained notoriety for Civil War battlefield photography (some of which was initially attributed to Brady). He also took seven portraits of President Abraham Lincoln, including the famously haunting “cracked plate” image, also at the National Portrait Gallery. That same day, Feb. 5, 1865, a few weeks before his second inauguration, Lincoln also sat for a lighthearted portrait with his youngest son Tad, with whom he seemed inseparable.

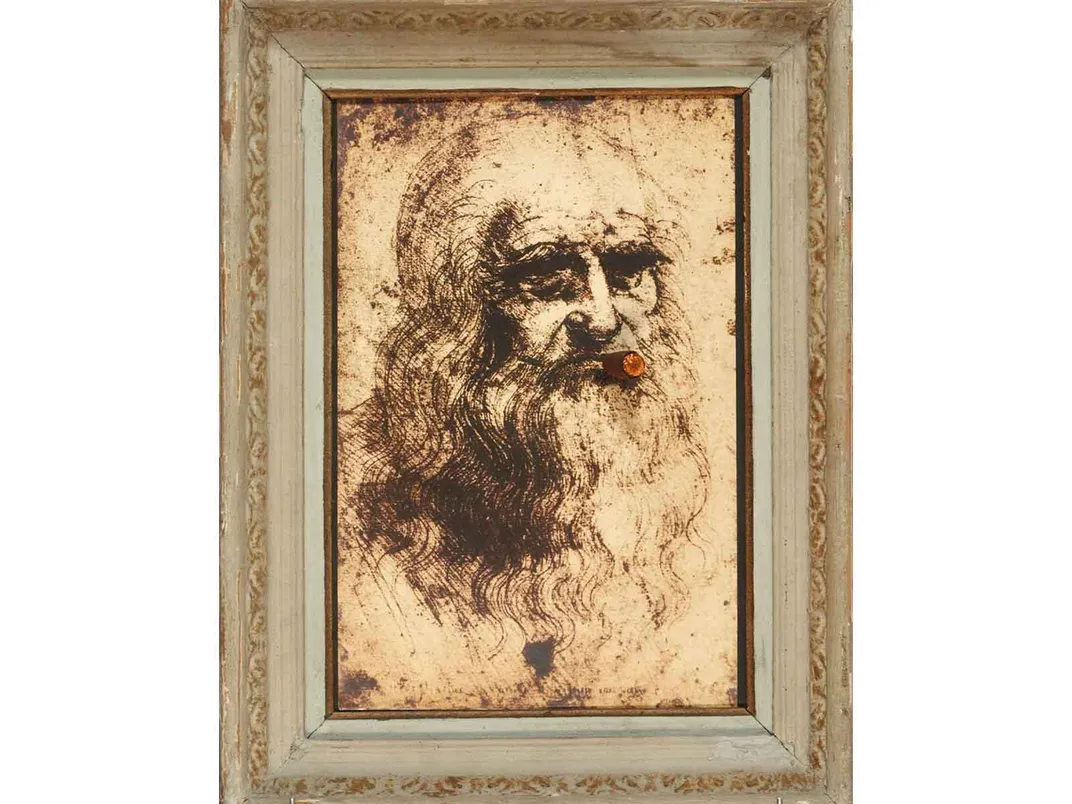

The Father of Mona Lisa by Man Ray

His longtime pal Marcel Duchamp may have famously drawn a mustache on an image of the Mona Lisa, but when it comes to defacing the Old Master behind that Renaissance icon, dadaist Man Ray seems to be in a more congratulatory mood. Taking the famous image in Leonardo Da Vinci’s 1512 self portrait Portrait of a Man in Red Chalk, he sticks an actual cigar in his mug for this 1967 work as if to say “Attaboy!”’ or “It’s a Masterpiece!” instead of “It’s a Girl!” It was produced in the third edition of the S.M.S. Portfolio, that collected work of artists including Duchamp, Christo, John Cage and Yoko Ono, and sent them out to subscribers.

Mother Earth and Father Sky by John L. Begay

Everyone has heard about Mother Earth, but not so much about Father Sky. He reigns above as she does below. But in this 1980 New Mexico sandpainting by Navajo artist John L. Begay held in the collections of the National Museum of the American Indian she gets the edge, since the medium is not stardust, but different colored sands. The practice of sandpainting was not intended to make art objects, but as key parts of healing rituals. The artist in this context was the medicine man and the person needing healing would sit in the sand art upon completion. This image is less ephemeral; its sand is affixed with glue onto particle board.

Filial Piety: Yang Hsiang Saving His Father From a Tiger by Katsushika Hokusai

Normally, children depend on fathers for protection. But in this dramatic scene, it is the 14-year-old Yang Hsiang who saves his father from the clutches of a tiger. Hokusai, the celebrated 19th-century Japanese artist, who gained fame with his Great Wave from his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, took the tale from the Confucian text of manners Classic of Filial Piety, which maintained “as they serve their fathers, so they serve their rulers, and they reverence them equally.” The kakemono, or hung scroll, was part of Charles Lang Freer’s original collection donated to create the Freer Gallery of Art, which when it opened in 1923 was the Smithsonian’s first art museum.

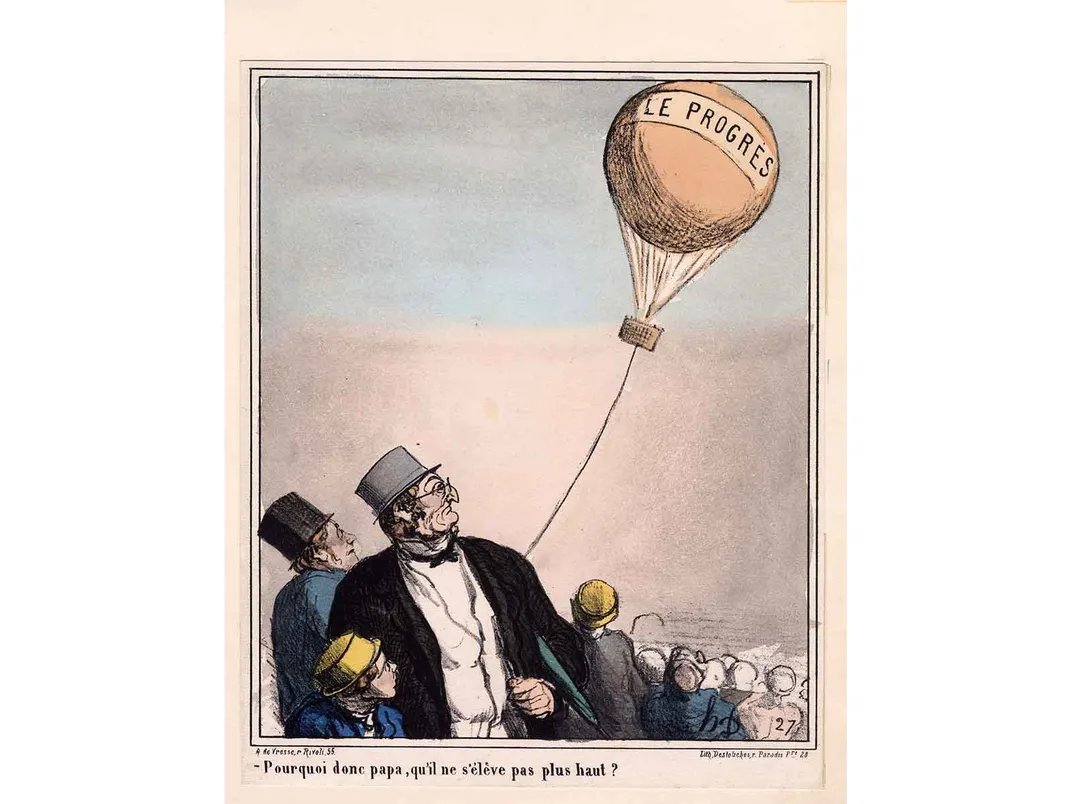

Pourquoi donc papa, qu'il ne s'élève pas plus haut? by Honoré Daumier

Fathers often enjoy sharing historic events with their young. So it might have been in this 1868 cartoon by Honoré Daumier when a bespectacled dad brings his son to see a balloon rise in France. Balloon aviation might have dated back to 1783, but it was still a marvel to witness into the 19th century. However, in this scene, part of Daumier’s Actualités series that commented on news of the day (of which this is No. 119), it is the boy who asks about the balloon labeled “Le Progrés,” or progress, “Why daddy, why doesn’t it rise higher?” The lithograph is part of a large collection of prints depicting early aviation at the National Air and Space Museum.

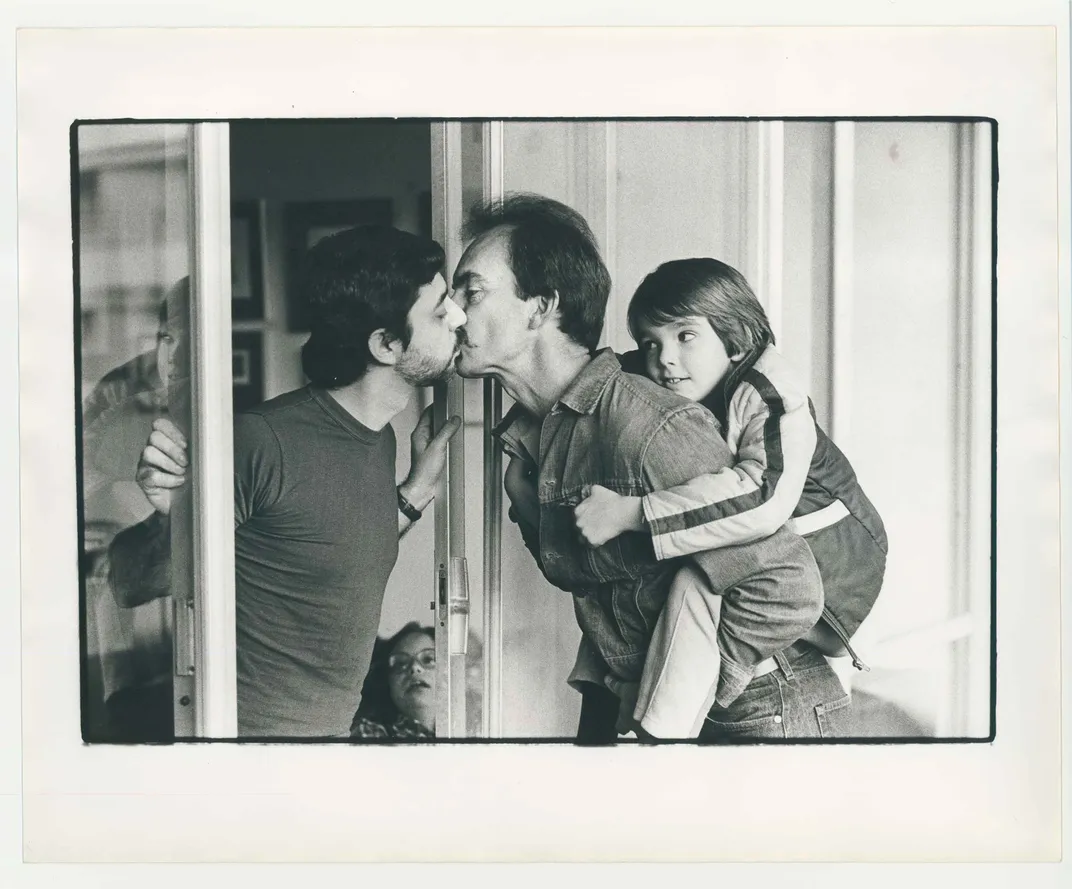

Gay Dads Kissing by J. Ross Baughman

Photojournalist J. Ross Baughman was just 23 when he won a Pulitzer Prize for photographs of Rhodesian Security Forces. He got another distinction when his image depicting a pair of gay fathers raising their four children in a combined household became one of the first sympathetic images of LGBTQ parenting to appear in a mass market publication. Although this image was made as part of a portfolio illustrating a May 1983 piece for Life Magazine by Anne Fadiman, “The Double Closet: How Two Gay Fathers Deal with Their Children and Ex Wives,” it first appeared in Christopher Street earlier that year and later was seen as a double page spread in Esquire in 1986. It eventually earned a place in the National Museum of American History.

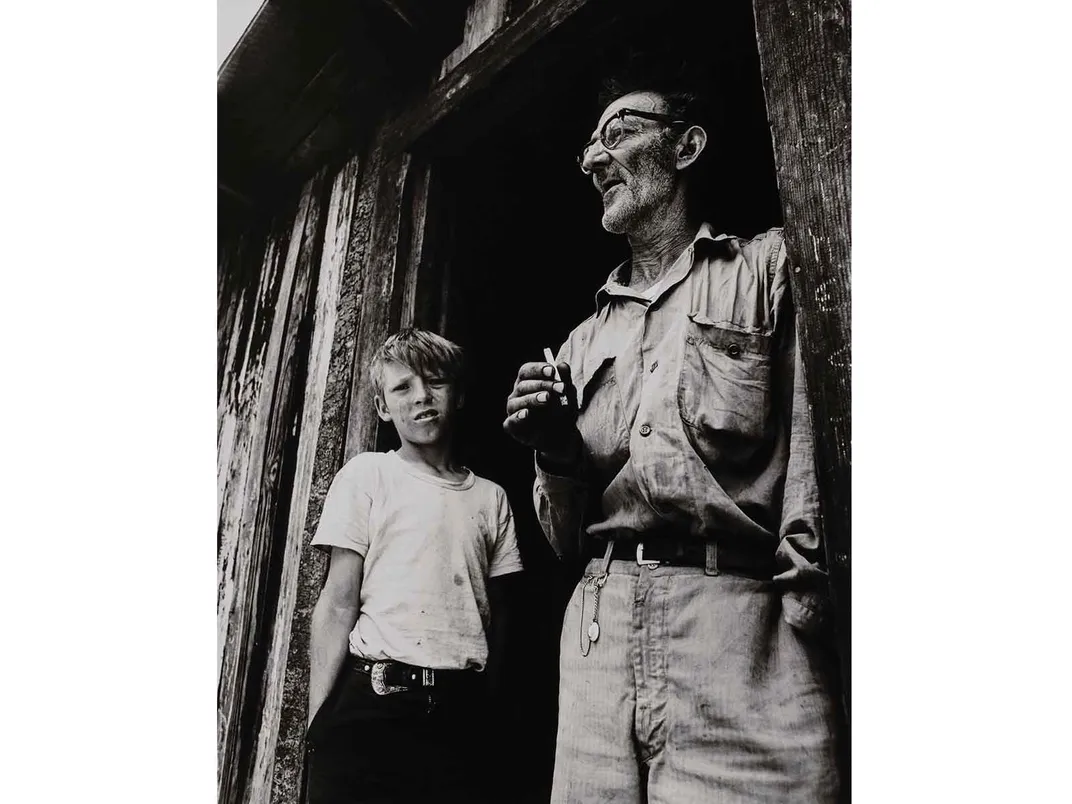

Appalachian Father and Son, Mingo County, West Virginia by Don Getsug

On the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty six years ago, photographer Don Getsug went back to look at some of the images he made in a 1970 trip to Appalachia the Rio Grande Valley, Mississippi and other pockets of lingering poverty. In a way he was reliving the stark, black and white artistry of the Farm Security Administration photographers that came before him, from Dorothea Lange to Walker Evans. “Conditions had not visibly changed,” he said in 2014 when he mounted a show of the work. Among them was this shot of a father and son he encountered in the coal country alongside the border of Kentucky and Virginia. A print is held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Father and Son by the Sea by Robert Broderson

The fiery, almost Francis Bacon-like faces in this undated work by American painter Robert Broderson (1920-1992) is quite different from much of his other, more straightforward figurative work, none of which were ever meant to be specific. The longtime teacher at Duke and North Carolina State once said his subjects “always tend more toward the imaginative than the real.” The ghostly faces here don’t suggest much of a connection between the two figures sitting on a dock, one boosted by a box as chair. But maybe the father and son here are not the humans at all; perhaps they are the pelicans.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/c2/a5c26d47-cf55-43c9-8897-c00199343f1a/fathers_mobile.png)

:focal(617x354:618x355)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/f9/57f9054e-2a93-4b0c-9b8d-cb3345467baa/fathers_social.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)