For More Than Five Decades, José Feliciano’s Version of the National Anthem Has Given Voice to Immigrant Pride

The acclaimed musician offers a moving welcome to the newest U.S. citizens and donates his guitar

:focal(2016x1497:2017x1498)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/d1/e0d17cd2-5754-489a-8e64-2e0f8300174a/feliciano2.jpg)

During the 1968 World Series, José Feliciano’s national anthem got almost as much attention as the battle between the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Cardinals. Before the series’ fifth game on October 7, the 23-year-old Puerto Rican-born performer seated himself on a stool in the playing field and sang the lyrics of the “Star-Spangled Banner” to a new tune with a Latin jazz twist. The audience responded immediately with both cheers and boos. Mostly angry fans jammed the switchboards at Tiger Stadium and at NBC, which was broadcasting the game. The irate callers thought Feliciano’s version of the national anthem was unpatriotic.

Because he was a long-haired young man wearing sunglasses, many viewers saw his performance as part of the Vietnam war protests. What most did not realize was that Feliciano had been born blind, so the sunglasses were not a fashion statement. He sat before the crowd alongside his guide dog Trudy and had absolutely no understanding of the spectacle he had ignited. Feliciano was shocked to hear the negative response. “When I did the anthem, I did it with the understanding in my heart and mind that I did it because I’m a patriot,” Feliciano said in an interview this week. “I was trying to be a grateful patriot. I was expressing my feelings for America when I did the anthem my way instead of just singing it with an orchestra.”

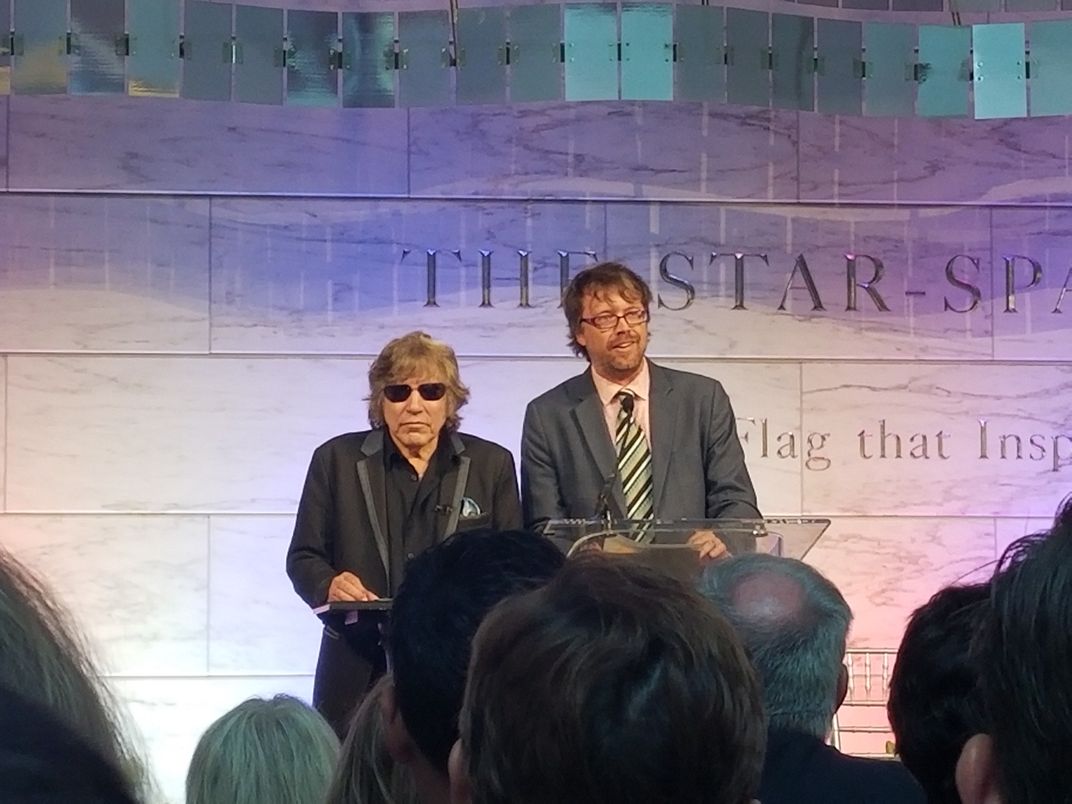

On Flag Day at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, Feliciano once again sang the national anthem his way in the museum's Star-Spangled Banner gallery as 20 immigrants from 17 nations took the oath that would transform them into American citizens. “You are now embarking on a great adventure,” Feliciano told the new citizens in his keynote address. “You are in a country that allows you to use your talents not only to better yourself, but to better the country.”

To mark this special day, Feliciano donated several items to the museum, including his treasured Concerto Candelas guitar, which he calls “the six-string lady.” It was built for him in 1967. He also contributed his well-used performance stool, an embroidered fan letter from an admirer in Japan, the Braille writer his wife Susan has used to generate documents over the years, and a personalized pair of sunglasses. The museum and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services hosted the ceremony.

Before the ceremony, Feliciano said that he hoped to convey to the new citizens “what it’s like for me to be an American, and they’re in for a treat. If they work hard, they’ll have no regrets. I have no regrets, though I was the first artist to stylize the national anthem, and I got a lot of protests for it. I have no regrets. America has been good to me. I’m glad that I’m here.”

Born in Puerto Rico, Feliciano moved with his family to New York City when he was five. His great ambition was to succeed as a singer, and he began performing in Greenwich Village clubs in the mid-1960s. By 1968, his career was skyrocketing after his 1967 hit album Feliciano, which won two Grammys, carried a scorching hot single—a cover of The Doors’ Light My Fire. However, his American recording career collapsed after Top 40 stations stopped airing his records in the wake of his World Series performance.

“That part of my life has been a bittersweet part,” he says. Here, my career was really swinging and radio stations stopped playing my records because of the anthem, but I thought to myself, ‘Well, it’s time to do other things, so I started playing in other places in the world . . . and I think it kept me going.”

Moving forward from that stunning day in Detroit was a challenge that he embraced. The furor over his anthem had begun even before he realized it. After the song, baseball announcer Tony Kubek told him, “You’ve created a commotion here. Veterans were throwing their shoes at the television.” NBC’s cameras stopped focusing on Feliciano after the song’s third line. The Detroit Free Press carried a headline in the next day’s editions that summed up the aftermath of Feliciano’s performance: “Storm Rages over Series Anthem.” Longtime Detroit Tigers play-by-play announcer Ernie Harwell, who had invited Feliciano to perform, almost lost his job because of anger over the singer’s performance.

Despite the controversy over his rendition of the national anthem, RCA released a single featuring Feliciano’s take on the nation’s song—and it rose to No. 50. New York Times writer Donal Henahan wrote that Americans had heard many performances of the anthem, and “the nation will no doubt survive the latest controversial version too.”

Feliciano’s biggest hit record in the United States after his infamous World Series appearance was 1970’s Feliz Navidad, now a classic considered one of the top 25 Christmas songs of all time. He has subsequently won six Grammy Awards from the Latin Recording Academy, plus a lifetime achievement award. He got a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1987.

Though many people condemned Feliciano’s World Series performance, his work provided an example for performers subsequently invited to sing the national anthem, and he hopes they have drawn inspiration from his anthem. “Today, personalized renditions of the national anthem are familiar to audiences,” says John Troutman, the museum's culture and the arts curator. “But in 1968, they were unheard of and often deemed unpatriotic. Feliciano’s donation helps illustrate the song’s use in popular culture.” Among those who have taken their own approach to the national anthem since 1968 are Jimi Hendrix, Marvin Gaye, Garth Brooks, Billy Joel, Whitney Houston, Lady Gaga and Beyoncé.

Since 1968, Feliciano has been invited to perform his version of the anthem at baseball and basketball games and at a campaign appearance for then-Democratic presidential candidate Walter Mondale in 1984. By 21st century standards, his “Star-Spangled Banner” seems entirely unobjectionable. Feliciano offers fans his own insights on the national anthem and reactions to his performance on his website.

In fact, the history of the traditional anthem is not entirely what many Americans would expect. Most are vaguely aware U.S. lawyer Francis Scott Key, then 35, composed the poem that provided the lyrics of the song in 1814 during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. He was aboard the British flagship trying to negotiate the release of a prisoner when the fleet began its attack. His poem, “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” later was paired with the existing musical trifle, “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a British tune born in the Anacreontic Society, an 18th-century London gentleman’s club. Anacreon was a Greek lyric poet celebrated as a “convivial bard” in this drinking song. From these somewhat-less-than-dignified beginnings, the song rose to become the national anthem in 1931.

Now sung in churches and most publicly at sporting events, the “sacred” nature of the song remains a topic for debate, as shown by the 2017 controversy over NFL players’ decision to “take a knee” while it was performed. The owners of NFL teams recently agreed unanimously to a pledge that players would stand during the anthem or remain in the locker room until after the song was performed. The plan, championed by President Donald Trump’s administration, promises to fine any team whose players showed disrespect for the national anthem.

Fifty years after his legendary performance, Feliciano looks back to Game 5 in the 1968 World Series as a turning point in his career, but it was not an ending by any means. He found new roads to success, and he never abandoned his patriotism. Just before his performance at the museum, Smithsonian Secretary David J. Skorton characterized Feliciano’s influence-blending rendition of the national anthem as “emblematic of the best features of this nation.” Upon hearing his “Star-Spangled Banner” today, the audience of mostly new citizens and their families erupted in thunderous applause interspersed with joyous whoops. Broad smiles ricocheted around the hall in a time of shared celebration and reflection. At events like this, Feliciano says he enjoys a moment to feel good about his work, his anthem, and his lifetime as an American.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)