A Chunk of Trinitite Reminds Us of the Sheer, Devastating Power of the Atomic Bomb

Within the Smithsonian’s collections exists a telltale trace of the weapon that would change the world forever

:focal(2254x1598:2255x1599)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/73/33733c2a-0d03-4e95-a5b5-e3ad76eb171e/sep2019_e02_prologue.jpg)

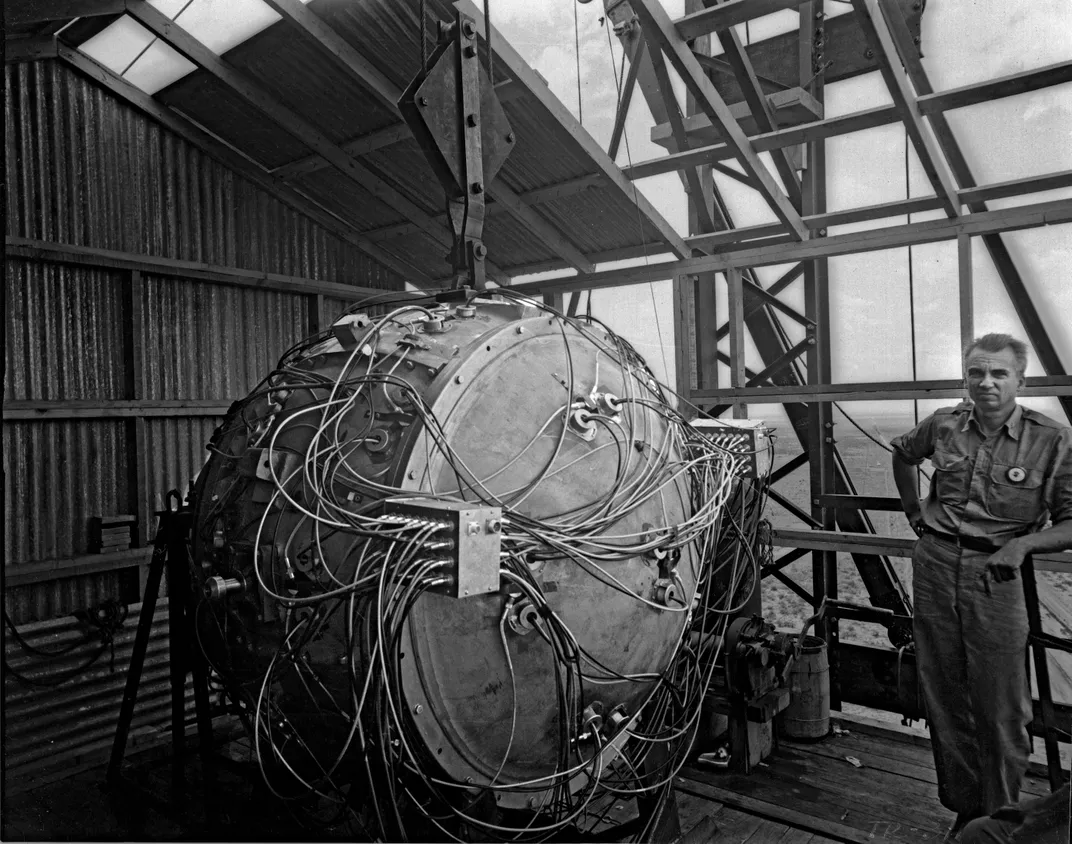

The first atomic bomb ever exploded was a test device, insouciantly nicknamed the Gadget. In mid-July 1945, American scientists had trucked the five-ton mechanism from their secret laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico, 230 miles south, to a place known to the scientists as Trinity in a stretch of southern New Mexico desert called the Jornada del Muerto—the journey of death. There they hoisted it into a corrugated-steel shelter on a 100-foot steel tower, connected the tangle of electric cables that would detonate its shell of high explosives, and waited tensely through a night of lightning and heavy rain before retreating to a blockhouse five and a half miles away to begin the test countdown.

The rain stopped and just at dawn on July 16, 1945, the explosion delivered a multiplying nuclear chain reaction in a sphere of plutonium no larger than a baseball that yielded an explosive force equivalent to about 19,000 tons of TNT. The 100-million-degree fireball vaporized the steel tower down to its footings, swirled up desert sand, melted it and rained down splashes of greenish glass before rising rapidly to form the world’s first nuclear mushroom cloud.

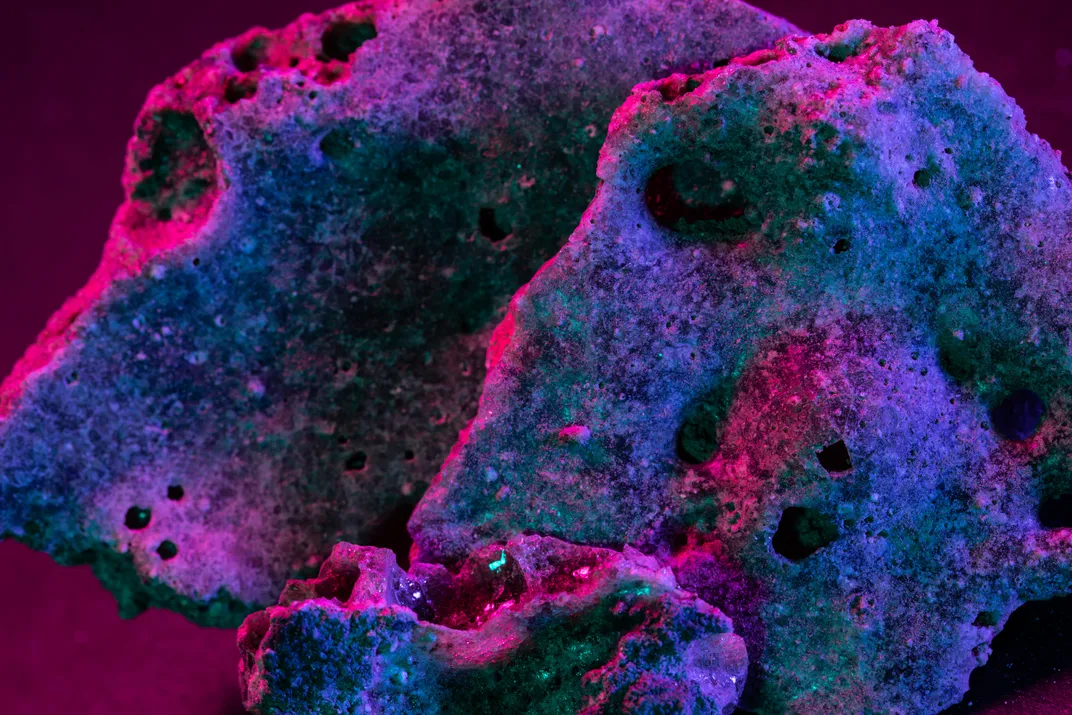

No one commented on the glass at the time—its creation was the least of the Gadget’s spectacular effects—but visitors to the site after the war noticed the unusual scattering of glassy mineral that surrounded the shallow bomb crater and began collecting pieces as souvenirs. “A lake of green jade,” Time magazine described it in September 1945. “The glass takes strange shapes—lopsided marbles, knobbly sheets a quarter-inch thick, broken, thin-walled bubbles, green, wormlike forms.” (Today, several samples of the substance, including the ones pictured here, reside at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.) At first no one knew what to call the material. Someone named it “Alamogordo glass” because the test site was near that town. A 1946 ad in Mechanix Illustrated offered jewelry made of “‘atomsite,’ the atomic-fused glass from the Trinity Site.” But the “-ite” suffix asked for something more specific than “atoms”: The whole world was made of atoms. At Los Alamos they turned to the site itself for a name—Trinitite. Still, where did “Trinity” come from?

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the charismatic theoretical physicist who had directed the Los Alamos Laboratory where the first atomic bombs were designed and built, was something of a Renaissance man, a poet as well as a scientist and administrator. It was he who had named the desert site “Trinity.” The domineering U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officer who had steered the Manhattan Project, Brig. Gen. Leslie R. Groves, later asked Oppenheimer why he picked such a strange name for a bomb testing range.

“Why I chose the name is not clear,” Oppenheimer responded, “but I know what thoughts were in my mind. There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love. From it a quotation:

As West and East

In all flat Maps—and I am one—are one,

So death doth touch the Resurrection.

“That still does not make a Trinity,” Oppenheimer continued, “but in another, better known devotional poem, Donne opens, ‘Batter my heart, three person’d God;—.’ Beyond this, I have no clues whatever.”

Oppenheimer could be obscure, not to say patronizing. Certainly he knew why he chose to name the test site after a poem by the pre-eminent metaphysical poet of Jacobean England, though he may not have cared to reveal himself to the gruff, no-nonsense Groves.

So the lopsided marbles and the knobbly sheets became Trinitite. It was primarily quartz and feldspar, tinted sea green with minerals in the desert sand, with droplets of condensed plutonium sealed into it. Once the site was opened, after the war, collectors picked it up in chunks; local rock shops sold it and still do. Concerned for its residual radioactivity, the Army bulldozed the site in 1952 and made collecting Trinitite illegal. What’s sold today was collected before the ban. Unless you eat it, scientists report, it isn’t dangerous anymore.

I bought a piece once as a birthday gift for a friend, the actor Paul Newman. Paul had been a 20-year-old rear gunner on a two-man Navy torpedo bomber, training for the invasion of Japan, when the second and third atomic bombs after Trinity exploded over Japan and did their part to end a war that killed more than 60 million human beings. “I was one of those who said thank god for the atomic bomb,” Paul told me ruefully.

He liked the Trinitite. It was a dusting of something he believed had spared his life along with the lives of at least tens of thousands of his comrades and hundreds of thousands of Japanese soldiers and civilians. Oppenheimer informed Groves in August 1945 that Los Alamos could probably produce at least six bombs a month by October if the Japanese continued the war.

To this day at Trinity, worker ants mending their tunnels push beads of Trinitite up into the sunlight, a memento mori in ravishing green glass.