Are Oysters an Aphrodisiac?

Sure, if you think so

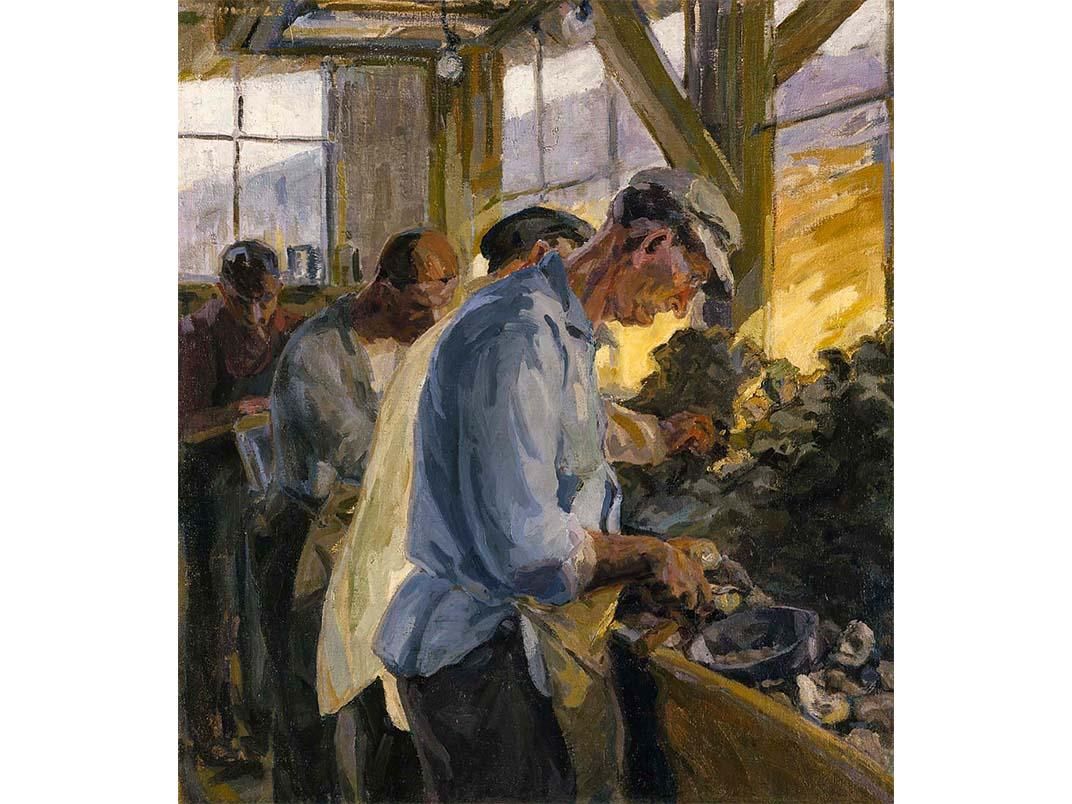

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6e/65/6e6570bf-a9d6-4c4f-8e8c-c743d1477f90/19521383a_1a.jpg)

For eons, men and women have searched for plants or foods that could turn on desire. And, to date, nothing has been scientifically proven to be an aphrodisiac—that is, to be a substance that sexually excites.

But that doesn’t stop millions of Google searches for sex-enhancing products or perennial Valentine's Day pronunciations that chocolate or honey or certain supplements will ignite the passion that’s been missing from your love life. Oysters have been a reputed aphrodisiac at least since the Roman Empire, and supposedly were regularly enjoyed as a virility-booster by Giacomo Girolamo Casanova. An enlightenment era polymath who lived from 1725 to 1798, Casanova became best known for having seduced more than 100 women, described at length in his memoir.

In 2005, the oyster as aphrodisiac got a big boost as many consumer publications reported that bivalve mollusks (which include clams, oysters, mussels and scallops) had been found to have desire-inducing properties. The stories came out of a presentation at the American Chemical Society by George Fisher, a professor of chemistry at Miami’s Barry University. Fisher and some colleagues discovered that mussels contained the amino acid, D-Aspartic acid, which has been found to increase the level of sex hormones in lab rats.

Even though the study did not involve oysters, Fisher was quoted in a number of publications speculating that perhaps the amino acid could contribute to an aphrodisiac effect. The effect of D-Aspartic acid in humans is still being studied. It may increase testosterone in sedentary men, but what it can do beyond that is not clear, according to a 2015 study published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition.

Michael Krychman has attempted to gather the available scientific evidence on so-called aphrodisiacs. “I think people are really suffering in silence and looking for good information and there isn’t a lot out there,” says Krychman, a sexual medicine gynecologist and counselor at the Southern California Center for Sexual Health and Survivorship Medicine in Newport Beach, California.

In a 2015 paper in the journal Sexual Medicine Reviews, Krychman found the risks of many substances people use to stimulate desire far outweigh any potential benefit—of which he found little. Oysters are safe to consume, but no scientific studies have been conducted to show they can stimulate desire. The bivalves do contain zinc, which has been found to be “an essential nutrient for testosterone production and spermatogenesis,” he wrote in the paper. They also contain “specific amino acids and serotonin, which are integral in the neural pathway of the pleasure response,” according to Krychman. But all of that does not an aphrodisiac make, he says.

Desire is complicated and not likely stimulated by a just a food or a supplement or a medication or psychotherapy alone, says Krychman. Food and exercise have an influence on well-being and salubrity; and “general health and sexual health are very much intertwined,” he says.

The challenge with studying oysters’ potential impact on desire: “there is a very large placebo effect,” says Krychman.

If his patients ask about oysters, he tells them “there is limited data to support their use.” But, adds Krychman, “if they like having oysters and it makes them feel better, then why not?”

Barry R. Komisaruk, a professor of psychology at Rutgers University, Newark, says he knows of no data proving that oysters have an aphrodisiac effect. So far, no one has discovered any substance that can truly turn on desire, says Komisaruk, who studies the neural pathways involved in sex and is a co-author of The Science of Orgasm.

Some recreational drugs—like marijuana—can intensify the sexual response, he says. But that's not true for everyone, according to the University of California, Santa Barbara, which maintains a sexual health and information website based on scientific findings. Marijuana can lead to heightened arousal, but it can also impair performance, and lower inhibitions, leading to riskier sexual activity, according to the site.

Alcohol can facilitate sexual interaction because it lowers inhibitions, says Komisaruk. But, as Shakespeare noted in Macbeth, alcohol “provokes the desire, but it takes away the performance.” Pharmaceuticals, like Viagra and Levitra, add potency to sexual response—but, adds Komisaruk, only if the desire is already there.

Desire is “a very tricky issue,” he says. “It’s complicated and nobody really understands it very well.”

Defined as a longing, or a craving, desire is essentially a feeling of deprivation, says Komisaruk. “There’s a pleasurable aspect of deprivation if you can satisfy that deprivation,” he says.

Could oysters possibly satisfy sexual deprivation? Maybe, says Komisaruk. But then again, maybe you’re just craving oysters.

It's your turn to Ask Smithsonian.

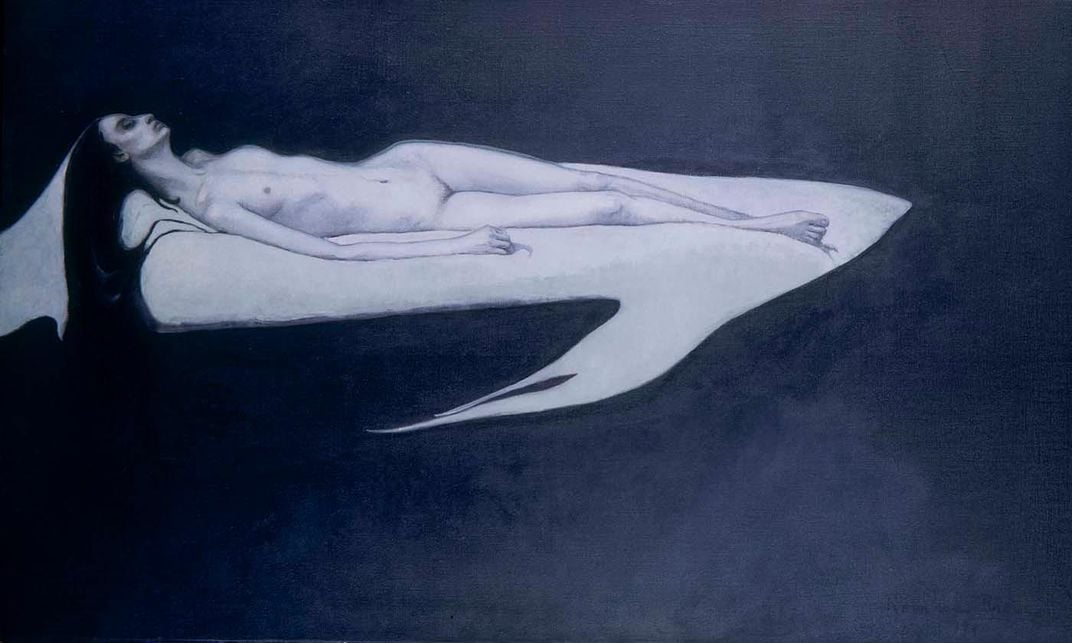

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/44/9e/449eae1c-009d-405c-9430-fbfa3142b5d4/npg78tc155sexexplosionrweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)