In Another Giant Leap, Apollo 11 Command Module Is 3-D Digitized for Humankind

Five decades after Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins journeyed to the moon, their spaceship finds a new digital life

One Tuesday morning, an hour before the National Air and Space Museum opened to the public, Adam Metallo, a 3-D digitization program officer at the Smithsonian Institution, stood in front of the Apollo 11 command module Columbia.

For 40 years, a Plexiglas “skin” had protected the module—which on July 16, 1969 launched Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins to the moon—but now it was nakedly exposed to the air.

More than $1.5 million worth of equipment, from lasers to structured light scanners to high-end cameras, surrounded the module, whose rusty, grizzled surface evoked Andrew Wyeth’s watercolor palette.

“We were asked about scanning the Apollo command module both inside and outside, and we gave an emphatic ‘Maybe’ to that question,” Metallo says. “This is one of the most complicated objects we could possibly scan.”

Typically, Metallo and colleague Vince Rossi, also a 3-D digitization program officer at the Institution, have a “grab bag” of about half a dozen categories of tools available for 3-D scanning projects, each of which might use one or two tool types. “This project uses pretty much everything we have in our lab,” he says. “We brought the lab on site here to the object.”

By scanning and photographing the exterior of the module as well, the team can do cross-sections and in the final digital product, offer perspectives on what it would be like to sit inside the module. Data will also be made available to those who want to do a 3-D print of the object. (Although a full-size print is theoretically possible, Rossi says scaled models are much more likely.)

“Three-dimensional printing is a great way to engage kids by creating a replica of such an iconic object either in the classroom or at home,” he says. “But the online model is really what we’re excited about.”

That online model will engage both young and older visitors, according to Allan Needell, curator of the human spaceflight Apollo collections at the museum.

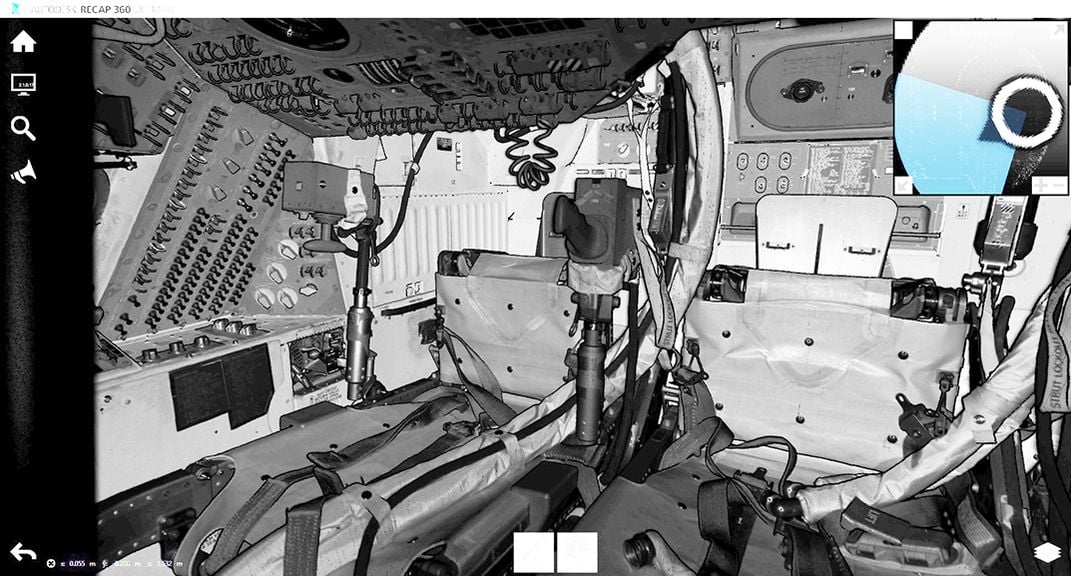

“They could look at old film and pictures, but now we have an opportunity to basically present to them an experience which is visually almost identical to if you were allowed to go in and lie down on one of those seats and look around,” he says.

The command module, which has been on display in the museum’s “Milestones” gallery since the museum opened in 1976 after being on exhibit at the Arts and Industries Building—where it was installed in 1970—will become the centerpiece of the museum’s new gallery “Destination Moon,” which will open at the end of the decade.

Laser scanners eschew certain reflective and shiny surfaces, which for the module presents quite a problem. “A very dark and shiny surface doesn’t reflect light back into the sensor as accurately as a nice, clean matte, white surface,” says Metallo.

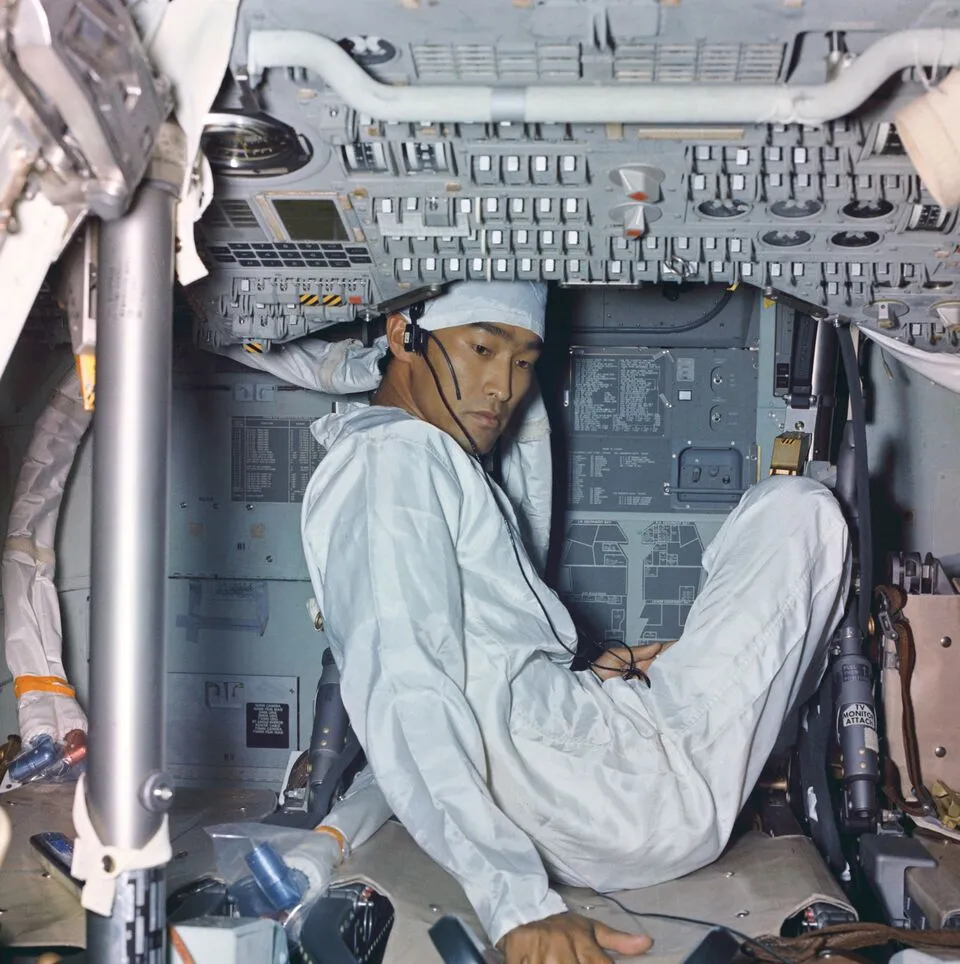

And most importantly for this project, the interior of the module is incredibly cramped and complex, and, to make matters more challenging, Metallo and Rossi aren’t allowed to touch the artifact, let alone to climb inside.

“We have a few tricks up our sleeves,” Metallo says with a smile.

He was also cheerful and philosophical about the technical challenges. “That’s integral to the story that we want to tell by scanning this object: what it’s like in there,” he says. “We can see the conditions that these astronauts went through and lived with. By scanning the interior with such fidelity and expressing that in 3-D models online and potentially in virtual reality, we’re going to be able to give the public a really profound experience and understanding of the object.”

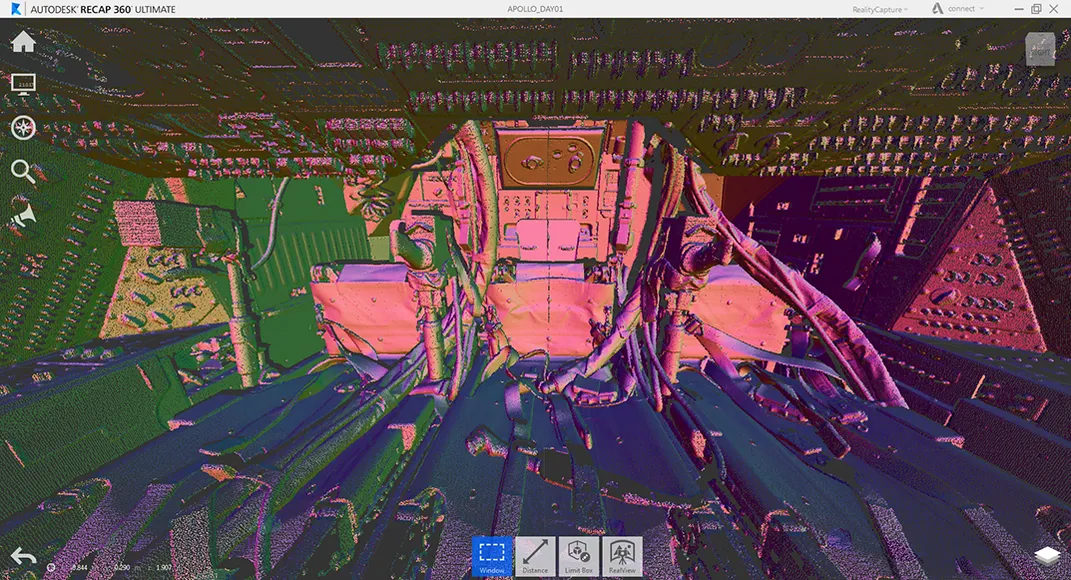

Unable to physically enter the module, the team used cameras on mechanical “arms” to reach inside and capture the interior’s nooks and crannies. Laser devices capture one million points per second. “It’s similar to a laser tape measure” capturing geometry, Rossi says, noting that the team will map photos onto the three-dimensional data. “We marry those two data sets,” he adds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/0d/610d345a-6bad-4115-a23f-23881ffc0b9a/a11interiormesh01v001web.jpg)

Moving the artifact offers the museum a rare chance to study and scan an otherwise inaccessible artifact. “We recognize that it has enormous cultural significance, as well as engineering and technical significance,” Needell says. “The challenge is how to take an object like this—and experiencing it—and translate it to a new generation of people who don’t have personal familiarity with it, and weren’t following it on their own.”

Although digital experiences of the command module will help engage that younger generation, a core and growing museum audience, the original module will remain on display. “That experience of ‘I actually stood next to the only part of that spacecraft that in 1969 took three astronauts to the vicinity of the moon and two of them to the surface—I stood next to it,’ that iconic feeling of being next to the real thing will be there,” says Needell.

The ingenuity of the module, which had to keep three men alive for two weeks as they hurdled through space, will become even more apparent in the scans, which will demonstrate to viewers how engineers solved technical problems. Seat belts, for example, were configured so that the astronauts had room to put on their space suits.

“We can show all of those kinds of things by being able to virtually tour the command module,” Needell said.

After eight days of scanning—and Rossi says every second will count—the team will process the enormous amount of collected data, and then will conduct a second scanning, some time in February, to fill in gaps. Each laser scan—about 50 will be completed—gather 6GB of data, and the 5DSR cameras will take thousands of pictures, 50 megapixels each. When this reporter noted that the hard drive on one of the laptops that Rossi and Metallo were using was nearly full, the latter said, “Thanks for noting.”

The two produced an iPhone and demonstrated the 3-D display of the museum’s 1903 Wright Flyer, which, like the Apollo module, was done in collaboration with software company Autodesk. The software, which viewers can use without downloading any plugins, maps and triangulates two-dimensional photos and uses them to create three-dimensional models.

“The version of the viewer that Autodesk helped us develop is a beta version. Of course we’re thinking about what a 1.0 version looks like,” Rossi said.

Brian Mathews, vice president and group chief technology officer at Autodesk, a software company headquartered in San Rafael, Californian, was on hand with some staff. “This technology is not even on the market yet, and this object is going to be perfect for it,” he said, as Autodesk employee and doctoral student Ronald Poelman demonstrated on a computer how the software pieced together images until the entire command module had been mapped out.

The 3-D models won’t seek to displace the presence of the original artifact, says Needell. “The artifact is not to be replaced by digital archives,” he adds. “They complement each other.”

The Apollo 11 Command Module is currently on view through September 2, 2019 in Seattle at the Museum of Flight in the traveling exhibition "Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission."

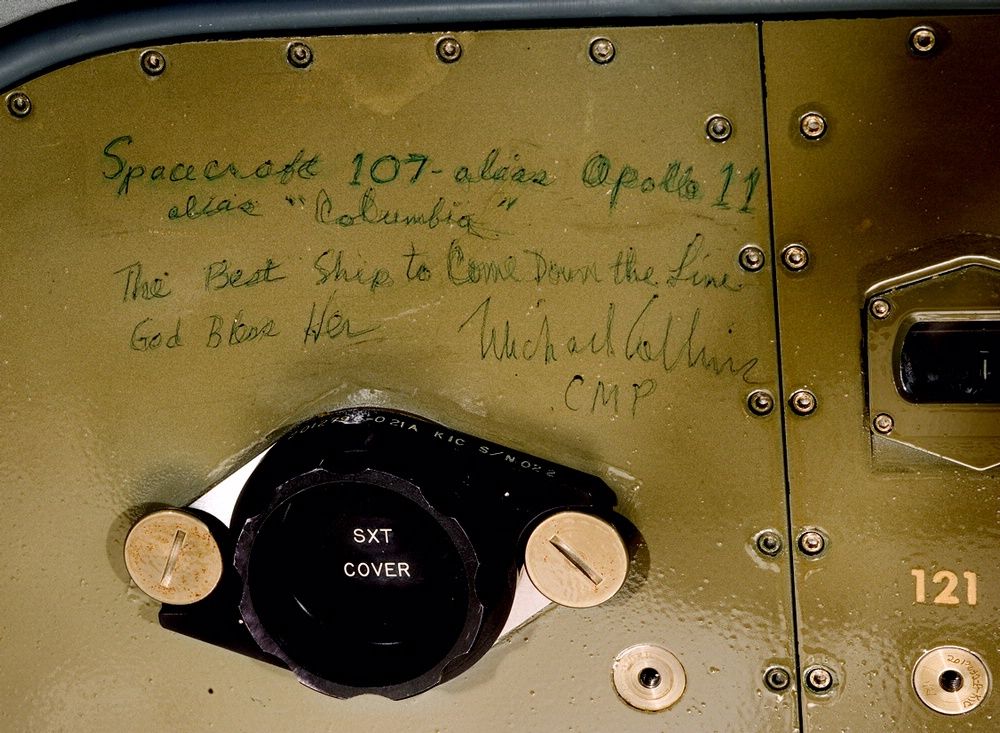

Update February 11, 2016: A calendar marking the days from lift off to landing, a cautionary note about “Smelly Waste,” as well as Michael Collins’ map that he used to attempt to locate the Eagle on the lunar surface are three of the newly discovered writings that have been uncovered as part of the massive scanning effort by the Smithsonian 3-D imaging specialists studying the Apollo 11 command module Columbia. The team spent two weeks photographing the module, using six different capture methods. Over the next two to three months, digitization specialists from Autodesk Inc. will be using the data to create the most detailed documented object of its size. The results will be unveiled this summer at the National Air and Space Museum. The team will be releasing the information online, as well, so that people with 3D printers can replicate the command module at home or in the classroom. A virtual reality experience using the data is also in the works.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)