How Researchers Are Reading Centuries-Old Letters Without Opening Them

A new technique enables scholars to unlock the secrets of long-sealed missives

:focal(392x224:393x225)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/8a/a08a581c-b98c-46c1-a852-ace79a74ef47/c9cdup5fhyjhtqcy6tk7kk-1024-80.gif)

Hundreds of years ago, letter writers used complicated paper folding tricks to keep their words hidden from prying eyes. But now, academic snoops equipped with 21st-century technology have foiled these letterlocking plans, using X-rays and 3-D imaging techniques to read the missives without unfolding them.

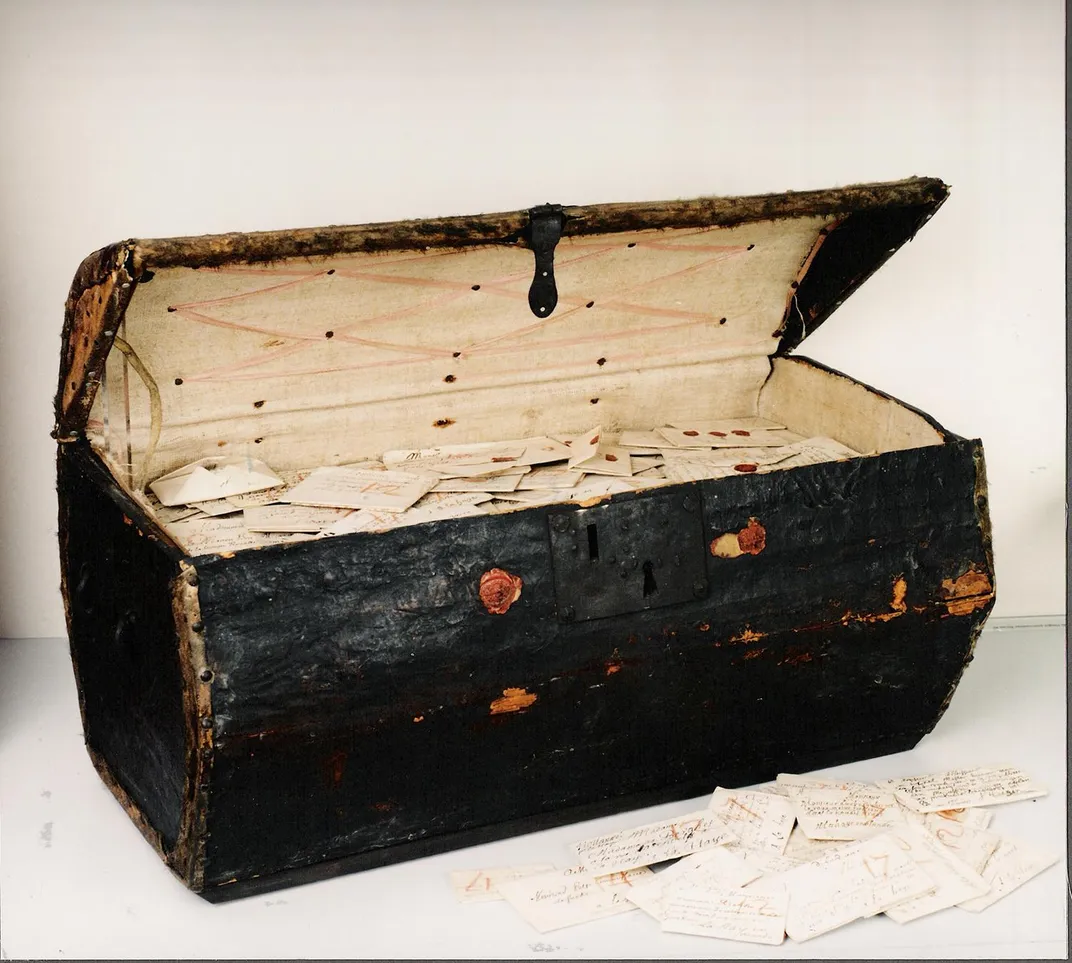

As Matt Simon reports for Wired, the researchers virtually “opened” four letters from the Brienne Collection, a trunk filled with 2,600 notes sent from Europe to the Hague between 1689 and 1706. The team published its findings in the journal Nature Communications.

“The letters in his trunk are so poignant, they tell such important stories about family and loss and love and religion,” study co-author Daniel Starza Smith, a literary historian at King’s College London, tells Wired. “But also, what letterlocking is doing is giving us a language to talk about sorts of technologies of human communication security and secrecy and discretion and privacy.”

People used letterlocking for hundreds of years, developing a huge variety of techniques for folding, cutting and interlocking the pages on which they wrote their correspondence. Depending on the technique, the recipient might need to rip the paper to open it, so the folding acted as a kind of tamper-evident seal. In some instances, a person familiar with the particular tricks used by the sender might be able to open it without tearing—but the uninitiated would be sure to rip it.

According to Atlas Obscura’s Abigail Cain, prominent practitioners of the secretive technique ran the gamut from Mary, Queen of Scots, to Galileo, Marie Antoinette and Niccolò Machiavelli.

“Letterlocking was an everyday activity for centuries, across cultures, borders, and social classes,” says lead author Jana Dambrogio, an MIT Libraries conservator, in a statement. “It plays an integral role in the history of secrecy systems as the missing link between physical communications security techniques from the ancient world and modern digital cryptography.”

Per William J. Broad of the New York Times, the researchers virtually opened the letters with an advanced X-ray machine that can produce three-dimensional images like those used in medical scans. They then used computers to analyze the folds and create a readable, digital model of the unfolded letter.

The Brienne Collection belonged to Simon and Marie de Brienne, who ran the postal service for the Hague, a central hub of European communications, in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. At the time, no postage stamps paid for by letter senders were used. Instead, the recipient of a letter would pay the postal service to deliver it. Typically, if a letter couldn’t be delivered, it would be destroyed. But the Briennes tried a different system, collecting undelivered letters in the hopes that the recipients would eventually show up to claim—and pay for—them. While some did, about 2,600 letters remained unclaimed.

When Simon de Brienne died in 1707, he left the trunk full of letters—and the possible payments that would come if they were ever claimed—to an orphanage. Two centuries later, in 1926, the chest and its contents were donated to the Ministry of Finance in the Hague.

“And then somehow some nerdy postage stamp people, like collectors, got wind of the fact that there was this chest of letters sitting in the Ministry of Finance,” co-author Rebekah Ahrendt, a music historian at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, tells Wired. “And they’re like, ‘Hey, can we have this? Because we actually want to start a postal museum.’ And the Ministry of Finance was like, ‘OK, cool idea. You can have it.’”

Today, six hundred letters in the collection remain unopened. Dambrogio tells the Times that scholars intend to keep them that way.

“We really need to keep the originals,” she says. “You can keep learning from them, especially if you keep the locked packets closed.”

So far, the team has only translated and read one of the letters in full. As Wired reports, it’s a 1697 missive from a man named Jacques Sennacques to his cousin, a French merchant living in the Hague, asking for a death certificate for his relative, Daniel Le Pers. Other letters in the collection are addressed to people from a variety of positions in European society, particularly those whose jobs kept them on the move, meaning they were no longer in the Hague by the time letters arrived for them.

“The trunk is a unique time capsule,” says co-author David van der Linden, a historian at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands, in the statement. “It preserves precious insights into the lives of thousands of people from all levels of society, including itinerant musicians, diplomats, and religious refugees. As historians, we regularly explore the lives of people who lived in the past, but to read an intimate story that has never seen the light of day—and never even reached its recipient—is truly extraordinary.”

In addition to analyzing the letters from the Brienne Collection, the researchers studied 250,000 historical letters, creating a method for categorizing letterlocking techniques and determining how secure they were.

The research team hopes to create a collection of letterlocking examples for scholars and students to use in their own research. Per the statement, the group also suggests that the virtual unfolding technique could be helpful in the analysis of other types of historical texts, including delicate scrolls and books.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)