Shackled Skeleton Reflects Brutal Reality of Slavery in Roman Britain

An enslaved man buried in England between 226 and 427 A.D. was interred with heavy iron fetters and a padlock around his ankles

:focal(465x386:466x387)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/8a/f38a9531-3fb4-4f69-974d-f39dc49b6314/great_casterton_roman_burial_shackles_c_mola_2.jpeg)

Written records testify that slavery was a common practice across the Roman Empire. But physical evidence of enslaved people’s lives is scarce, particularly in such remote regions as the island of Great Britain, which Rome occupied between 43 and 410 A.D.

Now, reports Mark Brown for the Guardian, the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) has revealed a striking exception to this trend: a Roman-era man whose remains represent the “clearest case of [the] burial of an enslaved individual” discovered in the United Kingdom to date. Researchers Chris Chinnock and Michael Marshall published their findings in the journal Britannia on Monday.

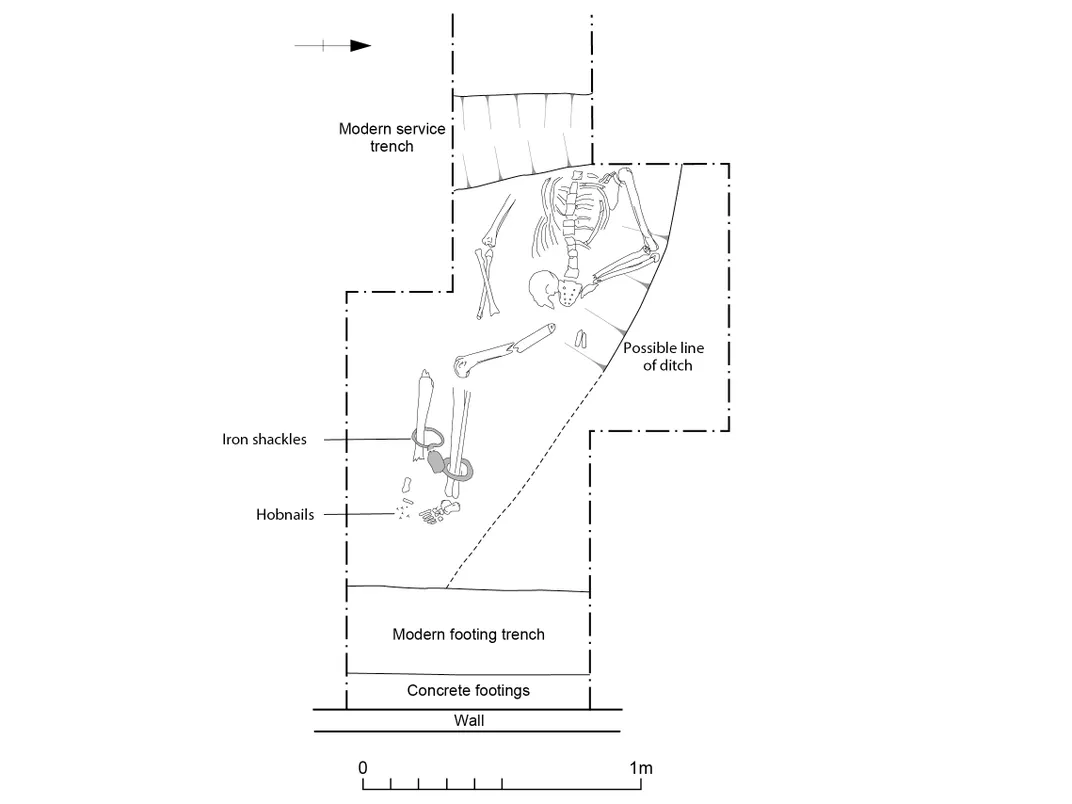

A construction crew renovating a private home in the English village of Great Casterton happened upon the ancient grave in 2015. Buried in a ditch, the enslaved man wore heavy iron shackles and a padlock around his ankles.

According to a MOLA statement, the find is notable in part because such restraints are rarely unearthed alongside human remains. Archaeologists have previously discovered victims of natural disasters whose still-shackled bodies were left unburied, but this does not appear to be the case with the Great Casterton man.

Radiocarbon testing undertaken by Leicestershire Police indicates that the remains date to between 226 and 427 A.D. Chinnock tells the Guardian that the man was likely between 26 and 35 years old when he died. He led a physically demanding life and had a healed bone spur that may have been caused by a blow or a fall. His precise cause of death remains unknown.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/76/e9765af5-483f-485b-99fc-96c64945d8cf/an_x-ray_of_the_great_casterton_shackles_and_padlock_c_mola.jpeg)

No evidence of a coffin exists, write the authors in the paper, and the “awkward” angle of the skeleton—resting slightly on the right side, with left side and arm elevated on a slope—suggests that it was thrown into a dirt ditch rather than properly interred. A Roman-era cemetery stood just under 200 feet away from the site, so this decision may have been “a conscious effort to separate or distinguish” the enslaved person, notes the statement.

What’s more, the individual(s) who buried this man appear to have gone out of their way to mark him as enslaved even in death.

“For living wearers, shackles were both a form of imprisonment and a method of punishment, a source of discomfort, pain and stigma which may have left scars even after they had been removed,” says Marshall in the statement.

Speaking with the Independent’s Samuel Osborne, the archaeologist adds that not all enslaved people in Roman times wore shackles: Instead, chaining one’s limbs together was reserved as brutal punishment for various perceived offenses, including attempting to escape.

“I can’t get past the idea that somebody was trying to make a point,” Marshall tells the Independent. “Whether that’s for the benefit of other people who are still alive, saying this person is a slave and will remain a slave even in death, or whether it is intended to have some sort of magical or religious dimension to it.”

Per the statement, some Roman burials found in Britain contained heavy iron rings that were wrapped around the deceased’s limbs. These objects did not function as actual restraints, but were likely added after death to mark their wearers as criminals or enslaved people. A handful of Roman writings from late antiquity hint at the belief that iron shackles could prevent the dead from coming back to haunt the living.

Such bonds, adds Marshall in the statement, “may have been used to exert power over dead bodies as well as the living, hinting that some of the symbolic consequences of imprisonment and slavery could extend even beyond death.”

Last month, archaeologists revealed further evidence of the brutal realities of Roman Britain when they announced the discovery of 52 ancient skeletons in Cambridgeshire, reports Jenny Gross for the New York Times. Of the bodies, 17 were decapitated sometime in the late third century A.D.—likely as a punishment for crimes, write University of Cambridge archaeologists in Britannia. Markings on two of the bodies indicated that these people had experienced “extreme violence,” including the removal of an ear, the authors added.

Chris Gosden, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the study, tells the Times that the list of crimes warranting death in the late Roman period included murder, stealing, religious misdeeds and many other offenses.

He explains, “Any hint of insurrection against the Roman state would’ve been dealt with extremely violently.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)