Follow a Couple’s Daring Escape From Slavery in the Antebellum South

A new short film from SCAD chronicles the lives of Ellen and William Craft, who disguised themselves to find freedom in 1848

:focal(485x304:486x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/3e/2c3ee68c-0dfd-4632-8d79-26b657d190b2/screen_shot_2021-08-26_at_81150_am.png)

In the days leading up to Christmas 1848, several travelers heading north along the East Coast encountered a wealthy but sickly white man and his companion, an enslaved Black man. What none of these individuals knew was that the strangers were actually a couple in the process of emancipating themselves from slavery. The story of Ellen and William Craft’s ingenious escape from bondage, and the rest of their eventful lives, forms the basis of a new short film from the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) in Savannah, Georgia.

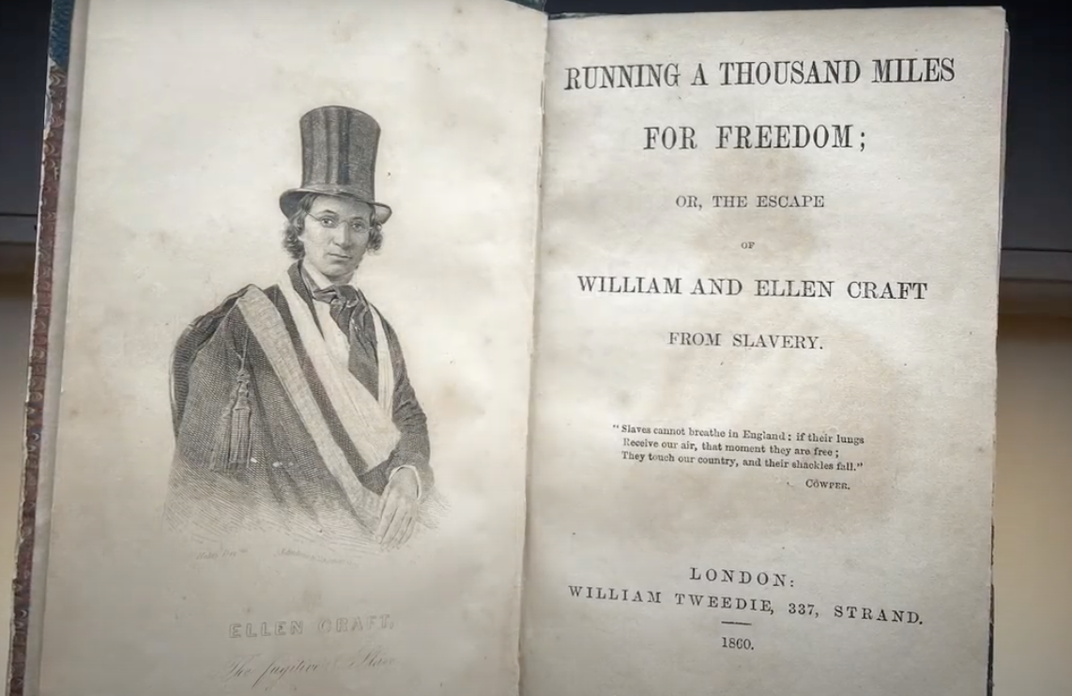

Titled A Thousand Miles and Counting, the documentary features commentary from three of the Crafts’ descendants. It’s based partially on the couple’s 1860 account of their journey, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom.

Per a statement, Walter O. Evans, a collector of African American art and member of the Board of Visitors at SCAD, first shared the Crafts’ story with SCAD President Paula Wallace in 2011. Evans explained that the Crafts traveled through the Central of Georgia Railway Depot, where the museum now stands.

The new film builds on SCAD’s previous efforts to publicize the couple’s escape from slavery. In 2016, the university honored the Crafts with a commemorative bronze medallion.

“Theirs is a true story of risk, ingenuity, bravery, triumph and dignity,” says Wallace in the statement. “[This account of] the journey of William and Ellen Craft … is one more example of SCAD’s commitment to the men and women who envisioned a better future.”

William and Ellen were born into slavery in Georgia in the mid-1820s. According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, Ellen was the daughter of an enslaved African American woman and her white enslaver. Ellen’s physical appearance allowed her to pass as white.

“They thought of a scheme whereby she would change gender, race and class,” says Evans in the documentary. “She would dress up in a man’s outfit—top hat, coat—and he would be her manservant.”

Since the Crafts couldn’t read or write, Ellen put her arm in a sling and faked an injury, wrote Thad Morgan for History.com in 2020. She also applied poultices to her neck to give herself an excuse not to speak and ensure that her voice wouldn’t give them away. The two escaped around Christmastime, when their enslavers gave them a few days off, and tried to get a head start before anyone realized they were missing.

As Marian Smith Holmes recounted for Smithsonian magazine in 2010, the Crafts faced several close calls on their way north. At one point, Ellen found herself seated on a train beside a close friend of her enslaver who had known her for years. The man failed to recognize her, and Ellen feigned deafness to avoid speaking with him.

On Christmas morning, the couple arrived on free soil in Philadelphia.

“As I’ve gotten older, Christmas Day has a different meaning for me now,” says Vicki Davis Williams, one of the Crafts’ great-great-granddaughters, in the film, “because ... you imagine that for four days, if they had gotten caught, they would have been returned to their [enslavers] and brutally treated and maybe killed.”

The Crafts settled in Boston, where they established themselves as members of the city’s Black community. William, who had become a skilled cabinetmaker while he was enslaved, resumed his trade as a free man, while Ellen became a seamstress.

“The risk that they took to run away, at the core of that is that they just wanted to have a family. They just wanted to be a husband and wife,” says Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely, another great-great-granddaughter of the Crafts, in the movie. “They just wanted what all human beings want to have.”

But their lives were disrupted again with the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which left them vulnerable to re-enslavement. The couple fled again, this time to England. There, they had five children; gained the education they had been denied while enslaved; and became engaged in abolitionist work, including the publication of their book. After 18 years, the Crafts returned to Reconstruction-era Georgia and founded the Woodville Co-Operative Farm School for Black students, persevering despite harassment from the Ku Klux Klan.

“Their determination to help other people overcame their desire to be comfortable,” Preacely says.

In addition to releasing the documentary, the museum has published a curriculum guide about the couple for teachers and students in grades 6 through 12. The film is available to view for free on SCAD Museum of Art’s website.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)