Tens of Thousands of Artifacts Have Been Found in Colonial Philadelphia Toilets

Archaeologists excavating the site of the Museum of the American Revolution found a dozen privy pits full of pottery, printing supplies and animal bones

When the Museum of the American Revolution opens its doors in Philadelphia in the spring of 2017, it will feature plenty of artifacts from the original 13 colonies. It will also feature some history from under the building itself. That’s because archaeologists excavating the site of the museum discovered a dozen brick-lined privy pits clogged with more than 82,000 artifacts, as Nina Golgwoski at The Huffington Post reports.

Many of the outhouses or privies in an area known as Carter’s Alley were associated with businesses or private households and stretch from the first decades of the 1700s to the end of that century. The privies didn't just serve as human waste depositories, they were also used to dispose of household waste, like broken pottery and animal bones. Golgowski says one privy was full of pieces of seashells and land records link it to a button shop. The archaeologists from Commonwealth Heritage Group found 750 pieces of type in another privy near a printer’s establishment.

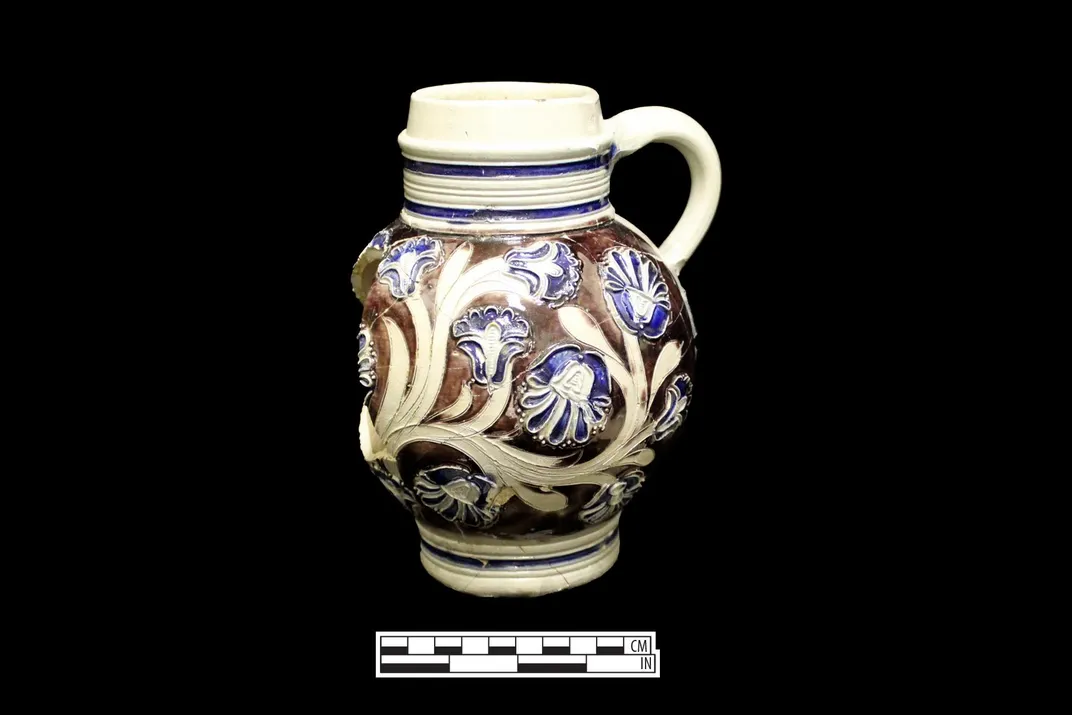

One of the most interesting privy pits was likely dug in 1776 by Benjamin and Mary Humphreys, Kristin Romey at National Geographic reports. The privy yielded dozens of drinking vessels, beer, wine and liquor bottles, broken tobacco pipes, serving dishes and broken punch bowls. It’s the detritus of a tavern, but there were no licensed taverns in that area. However, researchers found that in 1783, Mary Humphreys had been arrested for running a “disorderly house,” or an illegal tavern that often included prostitution. She was sent to the workhouse, and the privy was closed up soon after, perhaps to hide the evidence, a report on the excavation by the Commonwealth Heritage Group suggests.

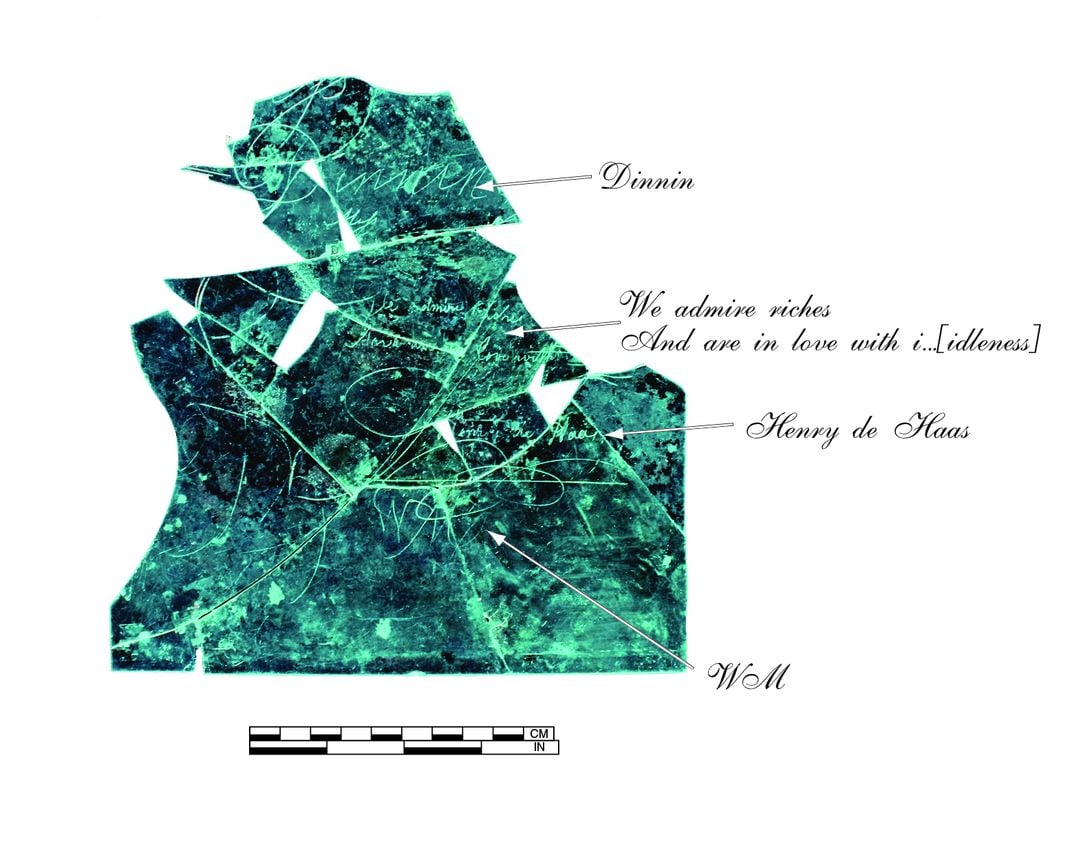

The report also highlights a windowpane excavated from the Humphreys' privy. Etched on the windowpane are the words “We admire riches, And are in love with i[dleness],” a line translated from a speech Cato the Younger gave the Roman senate in 63 B.C. condemning a group of conspirators plotting to overthrow the Republic. The line later appears in Joseph Addison’s play “Cato. A Tragedy” which was popular among colonial republicans. George Washington even had it performed for his troops at Valley Forge. Its meaning at the Humphreys' tavern depends on the intended audience. “Was it a rebuke of British tyranny, a barb aimed at local republicans, or just a joke made at the expense of fellow tavern goers?” the researchers ask in the report.

“This quote would have been known to people who were thinking politically in 18th-century Philadelphia,” principal archaeologist Rebecca Yamin tells Romey. “This man was writing a political message, which is so consistent with what we know was going on in the taverns at the time.”

Other artifacts found in the privies include wig curlers, sets of dishes and silverware, drinking tankards and tanning supplies. Animal bones from past meals were also very common in the privies.

Some of the artifacts will go on display in the new museum, including one of the Humphreys' punchbowls. It depicts the Triphena, the ship that the colonists sent to Britain in 1765 carrying a demand for the repeal of the hated Stamp Act.