Study of Narwhal Tusks Reveals a Swiftly Changing Arctic

Chemical analysis of ten tusks shows shifting diets and increasing levels of mercury as climate change warms the polar region

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/07/12070389-8d30-4984-9e50-62d78e2ad57c/narwhals-in-dense-pack-ice.jpg)

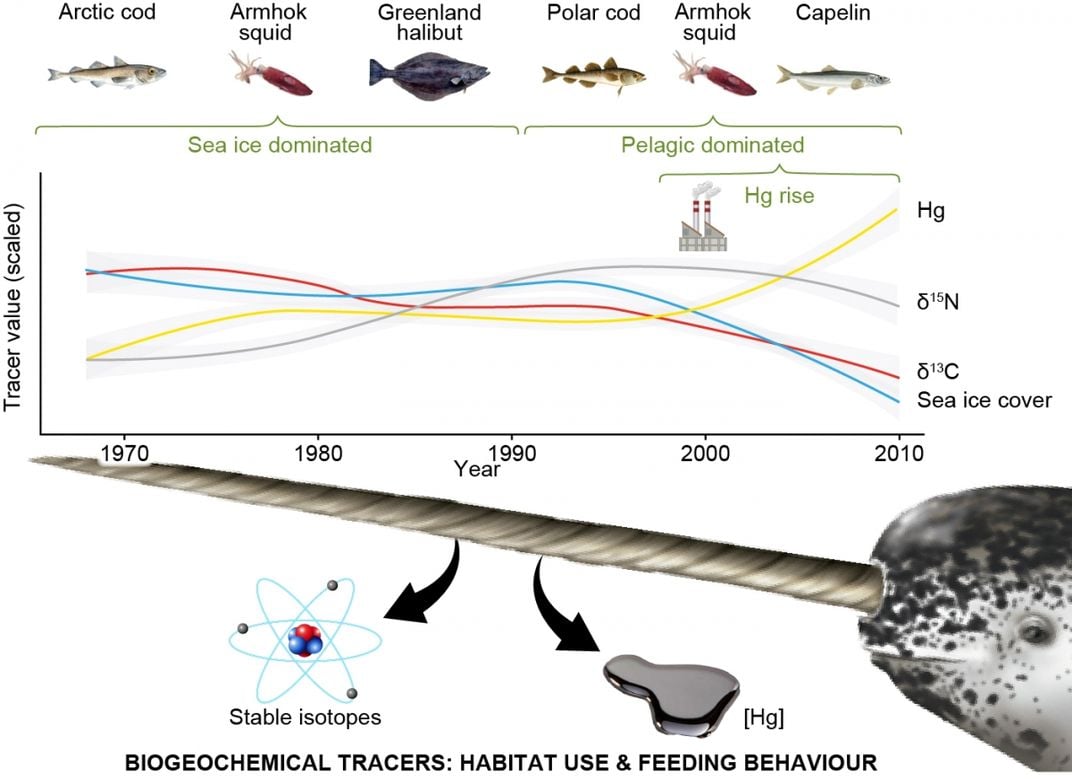

Male narwhals grow spiraling tusks throughout their lives that can reach lengths of up to ten feet. Now, analysis of these tusks reveals narwhals in the Arctic are altering their diets as climate change reduces the extent of sea ice. Warming and fossil fuel pollution may also be contributing to a large increase in concentrations of the toxic heavy metal mercury accumulating in the whales’ bodies, reports Molly Taft for Gizmodo.

The research, published last month in the journal Current Biology, looked at the chemical composition of ten tusks from whales killed by Inuit subsistence hunters off the coast of northwest Greenland, reports Ellie Shechet for Popular Science.

Since a narwhal’s tusk, which is actually a specialized tooth, grows in annual layers like the rings of a tree trunk, researchers can study the layers to look back in time, reports Matt Simon for Wired.

“Each of the individual layers in a tree gives you a lot of information about the condition of the tree in that year of growth,” Jean-Pierre Desforges, a wildlife toxicologist at McGill University, tells Gizmodo. “It’s the exact same way with a narwhal tusk. We can count up [the layers] and get a number on how old the animal is, and we can link each individual layer to a date in time, broadly speaking, to a year. If the animal is 50 years old, we can count 50 layers in a tusk, and date it back all the way to 1960.”

The tusks covered nearly a half century of a changing Arctic, from 1962 to 2010. Analysis of stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in the tusks revealed that around 1990, the whales’ diets moved away from large fish such as halibut and cod that are associated with ice-covered waters. Instead, the whales started to feed on smaller fish that tend to inhabit the open ocean. The change coincides with a precipitous drop in sea ice cover around the same time.

“This temporal pattern matches extremely well with what we know about sea ice extent in the Arctic, which after 1990 starts dropping pretty dramatically,” Desforges tells Wired.

The change might sound benign, but, according to Wired, these smaller, open-water fish tend to have a lower fat content, making them less nutritious for whales, who depend on calories to survive and pack on insulating blubber.

“If they're shifting prey to less Arctic species, that could be having an effect on their energy level intakes,” Desforges tells Wired. “Whether that is true is yet to be seen, but it's certainly the big question that we need to start asking themselves.”

The researchers also looked at changing levels of the neurotoxic heavy metal mercury in the whales’ bodies. Per the paper, mercury levels in the tusks’ layers increased 0.3 percent a year on average between 1962 and 2000, but the annual increase jumped to 1.9 percent between 2000 and 2010.

The timing of this sharp increase is puzzling because it occurs at the same time the whales started feeding on smaller fish that sit lower down on the food chain. Generally speaking, larger predators tend to contain higher levels of persistent toxins like mercury because they accumulate it from the smaller animals they eat. If this was the only factor in play, one would have expected the narwhals’ mercury levels to go down when they switched to eating smaller fishes.

The increase may suggest something worse: an increase in the amount of mercury entering the Arctic marine ecosystem.

“After the year 2000, the mercury pattern shifts away from a strong association with diet and it goes more toward the human impact angle,” Desforges tells Gizmodo. “We’re seeing changes in mercury that are disassociated with diet, meaning that humans are having an impact on mercury [in the ocean], especially in recent decades.”

In a statement, the researchers suggest that continued coal burning in Southeast Asia could be behind the uptick in mercury. But Gizmodo notes that ocean warming caused by climate change could also be driving the increase, as some research suggests higher water temperatures might cause fish to accumulate more of the toxic metal.

Lisa Loseto, a research scientist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada who was not involved in the study, tells Popular Science that considering climate change and contaminants together may help us understand the multiple stressors being inflicted on Arctic species. Loseto adds that the study shows “what one species is having to deal with in the Arctic—the place that’s enduring the most change.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)