The Snowmobile Changed How Americans Did Winter

As the cold comes in, snowbound communities are tuning up their vehicles and recreationists are making speedy winter plans

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/43/a2434ed0-d7ae-4143-a508-a9c0db2cee77/3930933611_7b3a97147b_b.jpg)

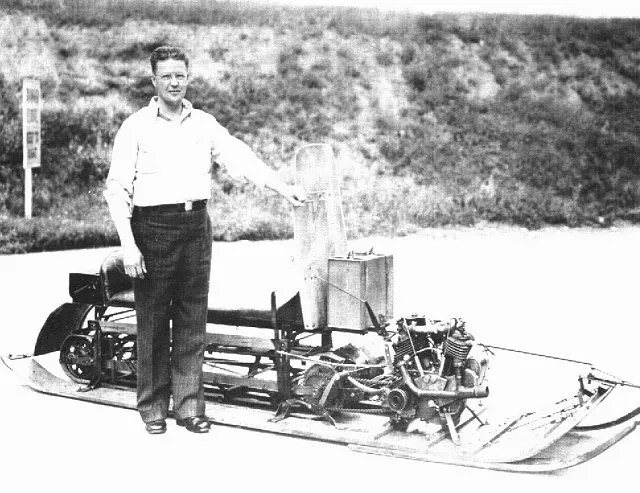

On November 22, 1927, an invention that forever changed our relationship with winter recreation was patented. Carl J.E. Eliason, from Sayner, Wisconsin, had been working on the “motor toboggan” since 1922. His patent of a “motor toboggan,” the precursor to the snowmobile, was a watershed moment in the history of snow travel.

Eliason’s invention “consisted of a wooden toboggan fitted with two skis steered by ropes and pushed along by a steel-cleated track powered by a 2.5 horse-power Johnson outboard motor,” writes author Larry McDonald. “Eliason patented his machine, and it was manufactured until 1960 by his company and, later, the FWD Corporation in Canada.”

Eliason wasn’t the first person to invent a motorized vehicle for snow travel. In the United States, writes Steve Pierce for Snowtech Magazine, the first patent for a snow vehicle was issued in 1896. Between then and Eliason’s patent, numerous people had worked on the problem—including Joseph Bombardier in Quebec, Canada, who went on to found Bombardier Inc, which grew from a maker of snow vehicles to a leading manufacturer of airplanes and trains.

But Eliason's 1927 patent stands out. According to Today in Science History, Eliason's design was the first snow vehicle to be both mass-produced and reliable for the rider. His design was widely copied.

The snowmobile changed how Americans (and their neighbors to the North) saw the challenges and opportunities of winter. While it offered snowbound communities unprecedented opportunities to travel in winter, it also created a totally new kind of winter recreation. Scholar Leonard S. Reich writes:

The snowmobile transformed northern winters with faster, easier travel and by making the experience so enjoyable that it became a form of recreation. In the case of some arctic peoples, snowmobiling gave them even more mobility in winter than in summer, enhancing communication among villages and between villages and towns. With snowmobiles to reach the grounds and bring back the game, hunting and fishing takes increased. Further south, people got out and about, visiting friends and taverns, making "snofaris" into the winter landscape, racing, ice fishing at distant ponds, taking themselves and their machines where they had never before been in winter and where machines had never been at all. Sounds of civilization echoed throughout the forest.

Of course, not everybody thought this was a good thing. As historian Michael J. Yochim documents, 1960s snowmobiling in Yellowstone and Glacier National Park caused significant conflicts between park rangers, conservationists, nature contemplators and recreationists. What is absolutely true is that the snowmobile changed winter forever.