Smithsonian Scholars Reflect on Baseball Legend Hank Aaron’s Legacy

The former home run king died in his sleep on Friday at age 86

:focal(815x327:816x328)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/91/c0913966-b5af-4d7c-ae4d-29b3633179c0/hank_aaron.jpg)

A trailblazing athlete who defied racism while chasing Major League Baseball’s (MLB) career home run record, Henry “Hank” Aaron, who died on Friday at age 86, often found himself fighting for respect.

“It was always this player and that player and then Henry Aaron,” he said following his Hall of Fame induction in 1982, according to Richard Goldstein of the New York Times, “but now I think I’m appreciated.”

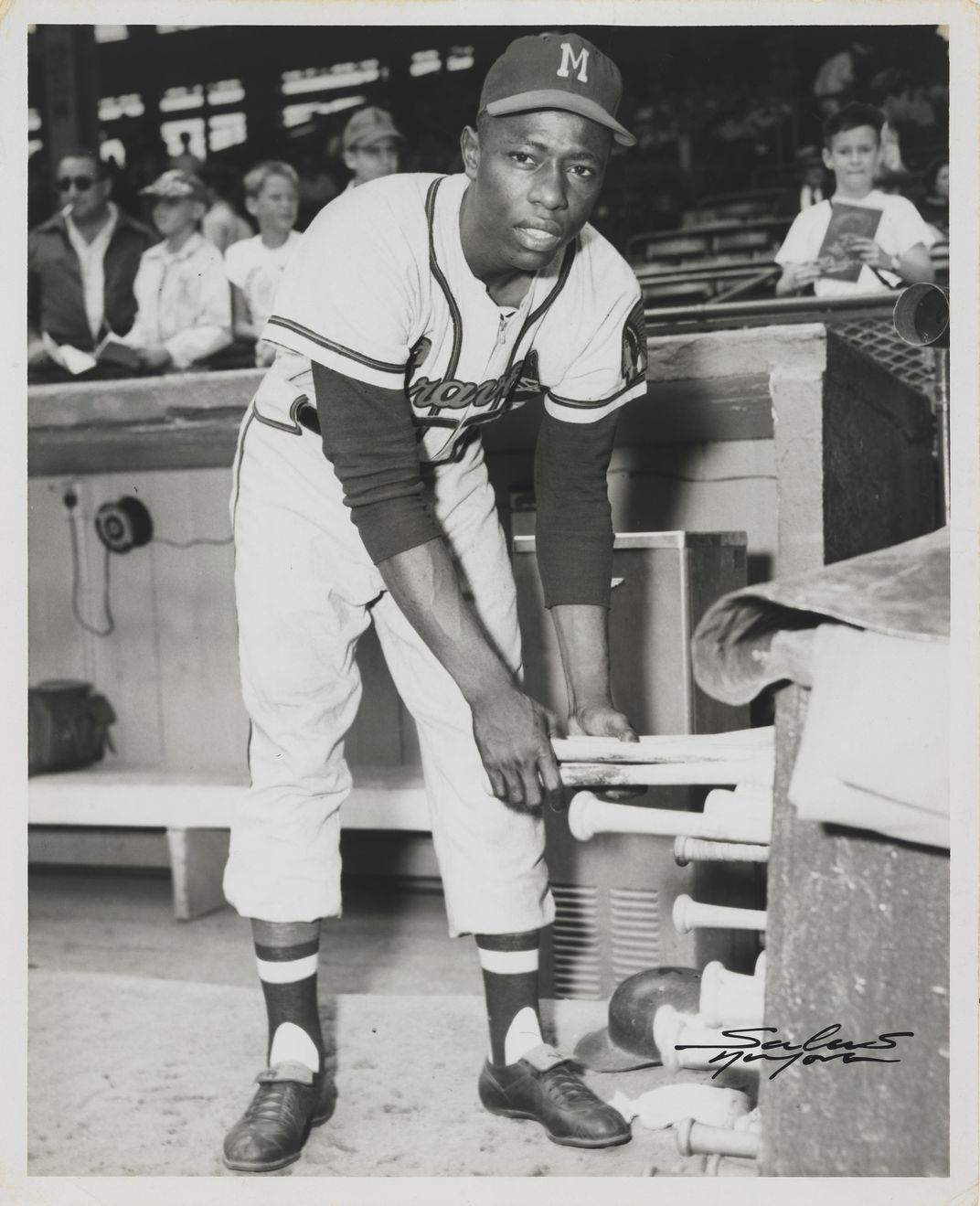

Aaron spent most of his career with the Braves, joining the Milwaukee team in 1954 and only departing for the Brewers in 1974. Now recognized as a baseball icon, he made his mark on the sport on April 8, 1974, scoring his 715th home run and surpassing Babe Ruth as the league’s all-time home run leader. By his retirement in 1976, he’d reached 755 home runs—a record he maintained until 2007, when Barry Bonds recorded a 756th home run.

As Baseball Reference notes, Aaron’s achievements across his 23-year MLB career were plentiful: He won the National League Most Valuable Player award in 1957 (the same year the Braves secured a victory over the New York Yankees in the World Series), earned consecutive National League pennants in 1957 and 1958, and nabbed three Golden Glove awards. He was also named an All-Star in all but his first and last seasons.

Statistical successes aside, Aaron’s career was distinguished by his dignity in the face of hatred. While playing in the Jim Crow South in the 1950s, he was denied meals and lodging afforded to his white teammates, writes Terrence Moore for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC); once, a guard shot at him as he returned to the training camp after hours. Aaron continued to receive racist hate mail as an established star, especially as he came closer to breaking the home run record.

“I think many people, including African Americans, found him to be symbolic of the idea of progress,” says Damion Thomas, a sports curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). “And what Hank Aaron’s success symbolizes for a lot of African Americans is ‘Look what we can do when you give us a chance to compete on equal terms.’”

“But for others,” Thomas adds, “it was a symbol that America was changing, and changing in ways that made them a bit uncomfortable.”

Born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1934, Aaron and his seven siblings grew up in a tight-knit family headed by his shipyard worker father and stay-at-home mother. Inspired by Jackie Robinson, who stopped by Mobile for a spring training game in 1948, the year after he broke MLB’s color barrier by joining the Brooklyn Dodgers, the young Aaron believed that a professional baseball career would offer an escape from segregation and poverty. He played with a semi-pro team before joining the Negro Leagues’ Indianapolis Clowns in 1951 and making his MLB debut in 1954.

In an email, Eric Jentsch, an entertainment and sports curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (NMAH), says, “He was a representative of the first generation of African American stars that not only integrated the game but provided an example for the integration of American society.”

Even after the Braves moved to Atlanta, a city with a relatively progressive reputation for the South, in 1966, Aaron endured racist vitriol while feeling only mildly supported by the overall fanbase. He kept the worst of the 930,000 letters he received from fans in a box in his attic, according to the AJC, and turned all threats of violence over to the FBI.

Reflecting on the events leading up to his historic home run in a 1994 interview with the Times’ William C. Rhoden, Aaron said, “It really made me see for the first time a clear picture of what this country is about. My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp.”

The baseball legend added, “I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ball parks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. They carved a piece of my heart away.”

Following the 1974 season, Aaron was traded to the Milwaukee Brewers, where he spent his final two seasons. Shortly after hanging up his cleats, he accepted a position as a Braves executive, becoming—for a time—the sport’s only black executive, according to the Washington Post.

Aaron dedicated much of his post-baseball career to entrepreneurship. As the AJC reports, the baseball legend owned eight Arby’s fast-food franchises in Milwaukee and two car dealerships in Atlanta. He also began speaking up about what he perceived as shortcomings within the sport, discussing the league’s hesitation to embrace black leadership in coaching, managerial and executive roles. As former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young previously told the AJC, these opinions didn’t represent a shift in Aaron’s mindset.

“It wasn’t that he became any more outspoken and started to pop off. People just began to ask him questions,” Young said. “As long as he was playing, they were asking Hank about balls and strikes and pitchers and hitters. When he stopped playing, the questions changed, and he just responded to them.”

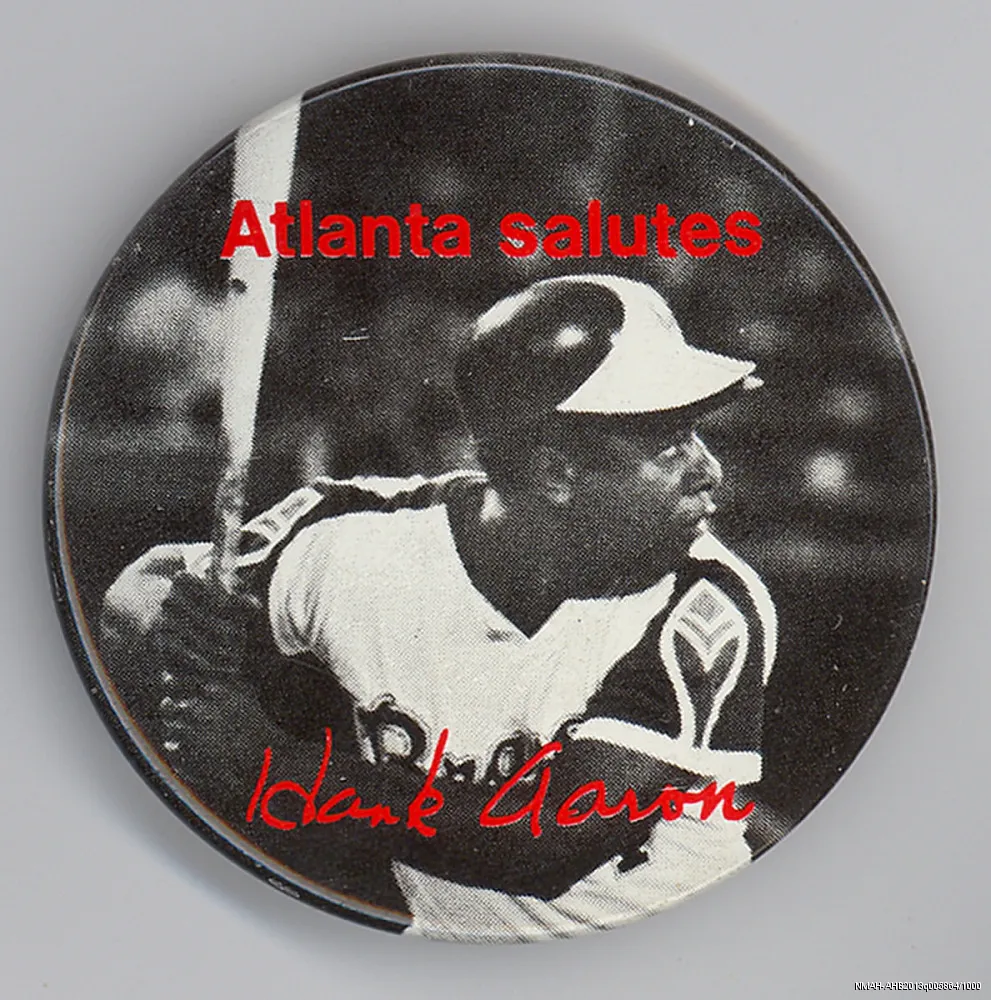

The Smithsonian Institution houses a number of artifacts linked to Aaron, including a photorealistic likeness of the athlete on view in the National Portrait Gallery’s “In Memoriam” exhibition, a bat used by Aaron in the 1957 All-Star Game and now in NMAH’s collections, and a signed Braves jersey that resides at the African American History Museum.

“Hank is part of a very important cohort of African American superstar athletes, who are now playing in these recently desegregated cities, and are symbols of their sports and symbols of a new era,” Thomas says. “You have an African American who was the star player, who is the MVP-level of all-time great, representing a city that staunchly fought to oppose integration and equal access. And I think that's part of the story that we often don't get when we think about someone like Hank Aaron and his generation.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/dc/8cdc9074-0c01-4b84-8632-cf8f910b1739/npg_2012_98_aaron_1l_r.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/7d/877da457-5cbf-4e1a-9cf0-2fc61db90aa7/nmaahc-2014_297_1_001.jpg)