Scientists Discover Ancient Black Hole From the Dawn of the Universe

Sitting some 13.1 billion light years away, the find offers a window into the early universe

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/0a/960abef7-0d6c-464b-97b3-518c2ca61b89/history-quasar-700x467.png)

Scientists discovered a monster of a black hole lurking at the distant reaches of the universe. It’s 800 million times the mass of our Sun, or over 175 times the mass of the black hole that resides in the center of our Milky Way Galaxy, Sagittarius A*.

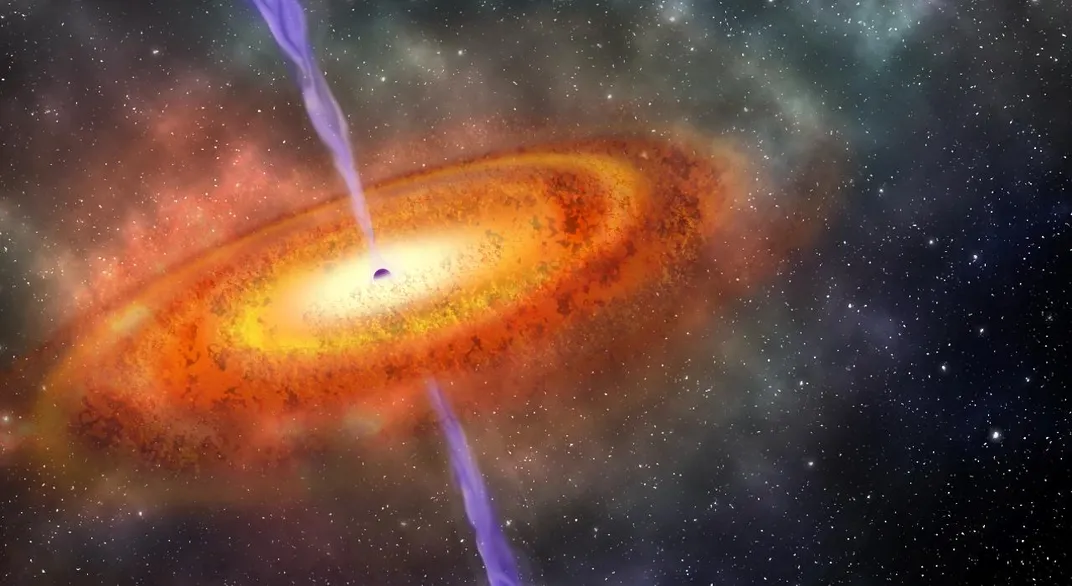

Discovered by a team of scientists led by Eduardo Bañados of The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science, the feature is unusual for both its activity and distance. Swirling gas and dust trapped by the black hole’s relentless gravitational field generate intense magnetic fields, in turn driving glaring jets. These jets transform the black hole into what's known as a quasar that is 400 trillion times brighter than our Sun. The researchers and described the find this week in two studies published in the journals Nature and Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The most interesting part of this object is its age. Because it takes time for light to travel across the vastness of space, astronomy is like a form of time travel: The most distant objects are also the oldest. The newly discovered black hole sits 13.1 billion light years away from the planet, which is also the amount of time it took for its first winks of light to reach us on Earth. That means the black hole formed just 690 million years after the Big Bang—60 million years earlier than the previously oldest-known quasar, reports Loren Grush at The Verge. While not long on the cosmic scale of our universe now, as Grush points out, that’s just 10 percent of the age of the universe at the time and a period of rapid transition.

After the Big Bang, the universe was in a literal Dark Age when particles were too energetic to form atoms, muchless light-emitting stars or galaxies. Over hundreds of millions of years as the universe expanded, the particles cooled, coming together first as atoms then stars, bringing an end to the pitch black.

Little is known about this transition from chaotic plasma to the first stars, but finding this quasar will help scientists explore the mystery. The team noticed missing spectral lines in the makeup of the black hole, reports Ryan Mandelbaum for Gizmodo. That means instead of being formed from ionized hydrogen, as is common now, most of the the hydrogen is neutral, suggesting the quasar formed during an early transitional period known as the Era of Reionization. That’s what makes this quasar so unique, explains Nell Greenfieldboyce for NPR: How could such a supermassive black hole grow so quickly at a time when stars were barely starting to form at all?

With just 20 to 100 of these supermassive black holes even theoretically predicted, this discovery is a rare and valued opportunity for a black hole to shine light on the early universe.