The Salty Sea Breeze Contains Microplastics, New Study Suggests

Researchers recorded the tiny particles in ocean air off the coast of France

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/ec/46ec5a92-4329-4527-a69f-95f53f0789f1/guss-b-jpimkaatgfq-unsplash_1.jpg)

Microplastics show up in soil, the deep ocean, beer, fish nurseries, table salt, bottled water, tea, all kinds of marine mammals, and human stool. One study published last year estimated that Americans might ingest as many as 121,000 of the particles per year. At less than 5 millimeters long, the tiny synthetic polymer particles are one of the most ubiquitous pollutants in our environment.

Thanks to a new study, researchers can add another microplastic-ridden thing to the list: the ocean breeze.

In a study published in Plos One, researchers from the University of Strathclyde and the Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées at the University of Toulouse recorded microplastics in the ocean air along the southwest Atlantic coast of France, reports Matt Simon for Wired. According to the study, researchers estimate that sea spray could release up to 136,000 tons of microplastic particles into the air per year.

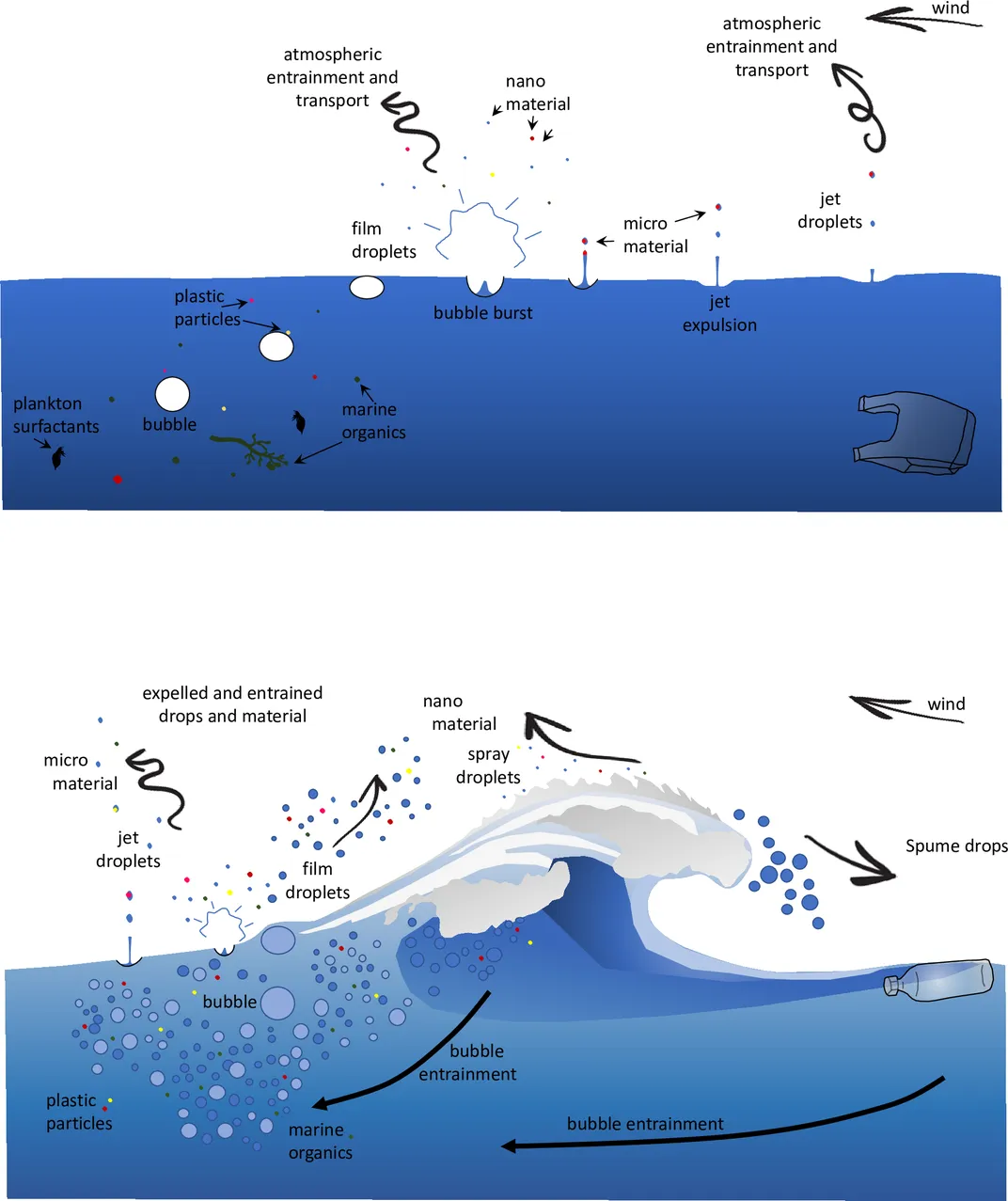

Researchers demonstrated in the laboratory how microplastics can be released into the air via “bubble burst ejection,” reports Karen McVeigh at the Guardian. The process works like this: Bubbles bring microplastics—as well as air, salts, bacteria and other particles—to the ocean’s surface. Then, when ocean waves break and cause those bubbles to burst, particles are launched into the winds blowing above the water.

This finding might help explain where “missing” plastic that enters the ocean has gone, Aristos Georgiou reports for Newsweek. “We have an estimated 12 million tonnes entering the sea every year but scientists have not managed to find where most of it goes—except in whales and other sea creatures—so we looked to see if some could be coming back out,” Deonie and Steve Allen, spouses and lead co-authors on the study, told Newsweek.

This means that oceans can act as both a sink and a source of microplastic pollution, Wired reports. “Previous studies have shown that plastics and microplastics can be washed onshore from the oceans, and that larger plastics can be blown onshore. But this is the first study to show that sea spray can release microplastics from the ocean,” University of Manchester earth scientist Ian Kane, who was not involved in the study, tells Wired. “Even if blown onshore, it is likely that much will make its way, eventually, into watercourses and the sea. Some may be sequestered into soil or vegetation and be ‘locked up’ indefinitely.”

Researchers recorded up to 19 microplastic fragments in a cubic meter of air along a low-pollution beach on the Bay of Biscay in Aquitaine, France. Deonie and Steve Allen tell Newsweek that this figure is "surprisingly high," specifically because the body of water they tested is not especially polluted.

“We know plastic moves in the atmosphere, we know it moves in water,” Steve Allen tells the Guardian. “Now we know it can come back. It is the first opening line of a new discussion.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)