For the First Time in Its 200-Year History, the Rijksmuseum Features Women Artists in ‘Gallery of Honour’

The Amsterdam institution is spotlighting works by Dutch Golden Age painters Judith Leyster, Gesina ter Borch and Rachel Ruysch

:focal(1838x1164:1839x1165)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/09/62098cea-8935-4fda-afeb-3b1e2d0cb70c/correct_omg.jpeg)

Visitors to the Rijksmuseum typically flock to the Gallery of Honour, a series of ornately decorated chambers that boast some of the Amsterdam museum’s star attractions, to see such masterpieces as Rembrandt’s Night Watch and Vermeer’s The Milkmaid.

But since the Dutch museum first opened its doors more than two centuries ago, no works by female artists have hung in this storied central hall. That changed this week, reports Isabel Ferrer for Spanish newspaper El País. As the museum announced via Twitter, staff marked International Women’s Day, March 8, by hanging three paintings by women artists in the Gallery of Honour for the first time in the institution’s history.

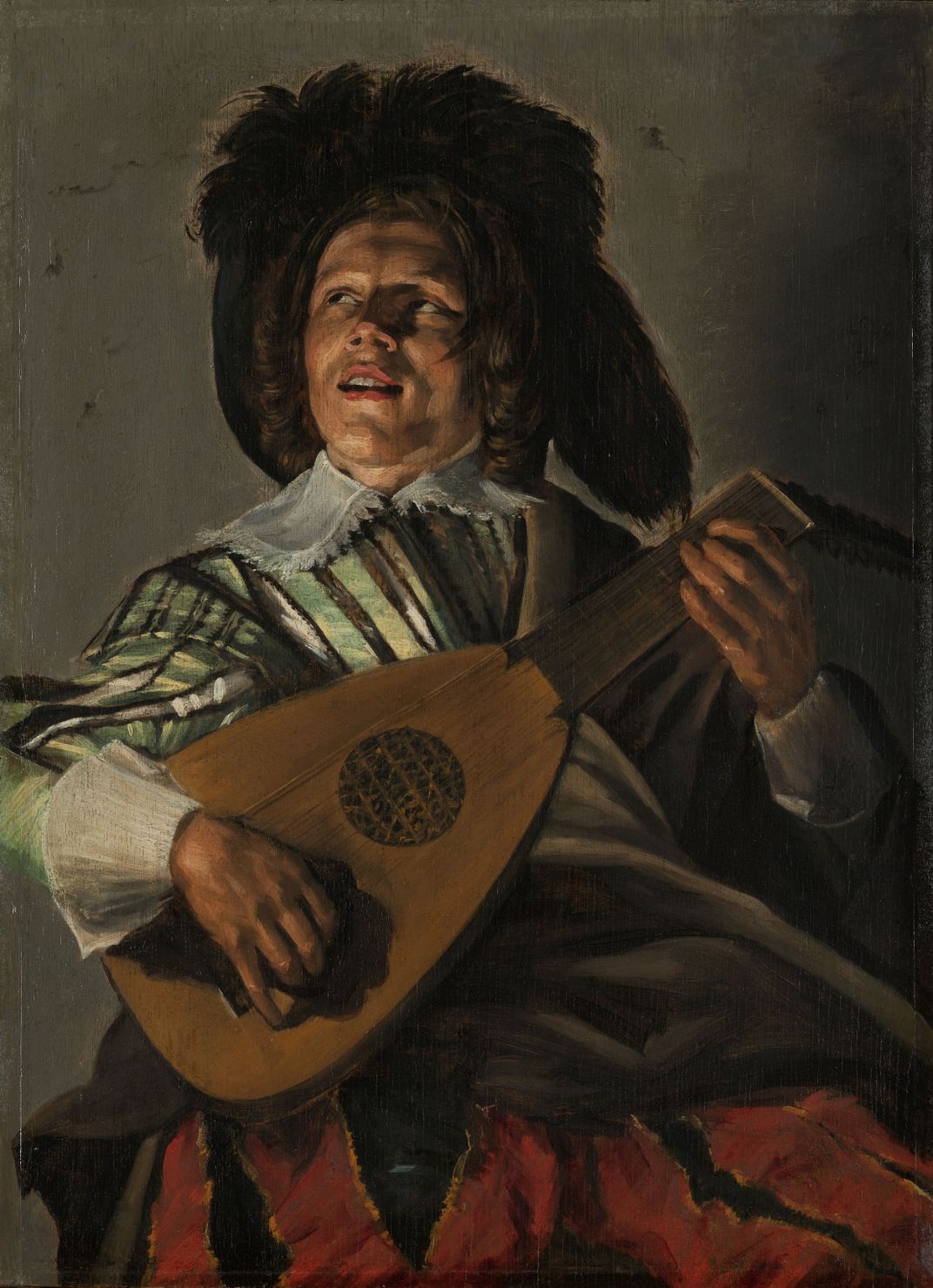

All three paintings—The Serenade (1629) by Judith Leyster, Memorial Portrait of Moses ter Borch (1667–1669) by Gesina ter Borch and her brother, and Still Life with Flowers in a Glass Vase (1690–1720) by Rachel Ruysch—were painted in or around the 17th century. During this period, sometimes referred to as the Dutch Golden Age, trade in enslaved people and unprecedented economic growth contributed to a period of prosperity and cultural productivity for the Netherlands’ elite.

Per a statement, the works will remain on permanent display in the gallery in an effort to “highlight the underexposure of women in Dutch cultural history.” Though the museum is currently closed to the public, viewers can view the works on the Rijksmuseum website or explore video interviews with curators about Ruysch and other female artists in the collections.

The change marks a key step in a research program dedicated to illuminating the roles of female artists, patrons, collectors, donors and curators who have contributed to the Rijksmuseum’s historic collections, as well as discovering the stories of the often-anonymous women portrayed in art.

“The museum is catching up in the field of women’s history,” says Jenny Reynaerts, curator of 19th-century painting at the Rijksmuseum, in the statement. “The Rijksmuseum’s permanent exhibition presents a picture of the culture of the Netherlands over the centuries. Remarkably little of this story, however, is told from a female perspective. This is evident both in the composition of the collection and in the lack of documented knowledge of the role of women in Dutch history.”

Despite the relative dearth of knowledge surrounding these female artists, researchers do have a sense of the broad strokes of their lives. As Rebecca Appel notes for Google Arts & Culture, Leyster (1609–1666) was highly esteemed by her contemporaries but remained unrecognized by art historians until the late 19th century, in part due to her habit of simply signing paintings “JL.”

Arguably the most prominent female painter of the period, Leyster boasted “her own workshop, her own students and her own style, one that combined the spontaneity of [Frans] Hals’ brushwork with a Caravaggist chiaroscuro,” wrote Karen Rosenberg for the New York Times in 2009. Known for her vibrant genre paintings and self-portraits, her creative output fell drastically after she married fellow artist Jan Miense Molenaer and started a family.

Per the Times, “We don’t know whether Leyster formally subsumed her career to her husband’s or just couldn’t find the time to do her own work in between raising three children and managing the family’s financial affairs.”

Ruysch (1664–1750), meanwhile, was widely recognized as an accomplished painter during her lifetime, says curator Cèlia Querol Torello in a video interview. She earned a membership in the painter’s guild at the Hague—the first women to ever join the organization—and later became a court painter in Dusseldorf.

“She married, gave birth to ten children, painted all her life, made a very good living out of it, and enjoyed the recognition of her fellow painters,” Querol Torello adds.

Ruysch made a name for herself by painting still life works of flowers, such as the one hung in the Gallery of Honour. In this work, says Querol Torello, “[w]e see an abundance of different colors and shapes and flowers,” including roses, carnations, tulips, hyacinths and poppies, framed against a dramatic dark background. “[Ruysch] was the daughter of a botanist … which explains her passion for the natural world.”

Ter Borch, finally, never held a formal apprenticeship, joined a guild, displayed her work publicly or sold one of her creations. But as Nicole E. Cook explained for Art Herstory in 2019, “[S]he created hundreds of finely painted, immediately captivating drawings and paintings over the course of her lifetime. Gesina ter Borch was an artist and she thought of herself as an artist, as her multiple self-portraits and allegorical imagery attest.”

According to Claire Selvin of ARTNews, the new initiative marks yet another effort on the Rijksmuseum’s part to examine the gaps in its collections. A major exhibition slated to debut this spring will explore Dutch connections to colonialism and the enslavement of people in Brazil, Suriname, the Caribbean, South Africa and Asia.

“Women play an important role in the cultural history of the Netherlands. Until now, however, women have been missing from the Rijksmuseum’s Gallery of Honour,” says director Taco Dibbits in the statement. “By asking new questions and studying a range of sources and objects, we can provide a more complete story of the Netherlands.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)